LONDON — On May 13, 1907, Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky and Joseph Stalin stood in a London church as the Fifth Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party planned a revolution.

Just 10 years later, as the Bolshevik-led October Revolution of 1917 took place, a new world order was born.

For those who grew up in the subsequent Cold War in which the communist and free worlds fought for ascendancy, the attractions of socialist utopias, erected upon the corpses of many millions of ordinary people, never held any attraction. However, for a new generation that came of age as communism was being consigned to the history books, socialism has emerged as a strangely attractive proposition.

This phenomenon is known as “millennial socialism.” And it reflects a positive view of socialism and communism held among some Americans born between 1980 and 1996. This has been borne out in some recent polls.

For example, a 2019 YouGov poll found that more than a third of U.S. millennials now approve of communism. In the same poll, 70% of U.S. millennials polled said “they would be at least somewhat likely to vote for a socialist candidate.”

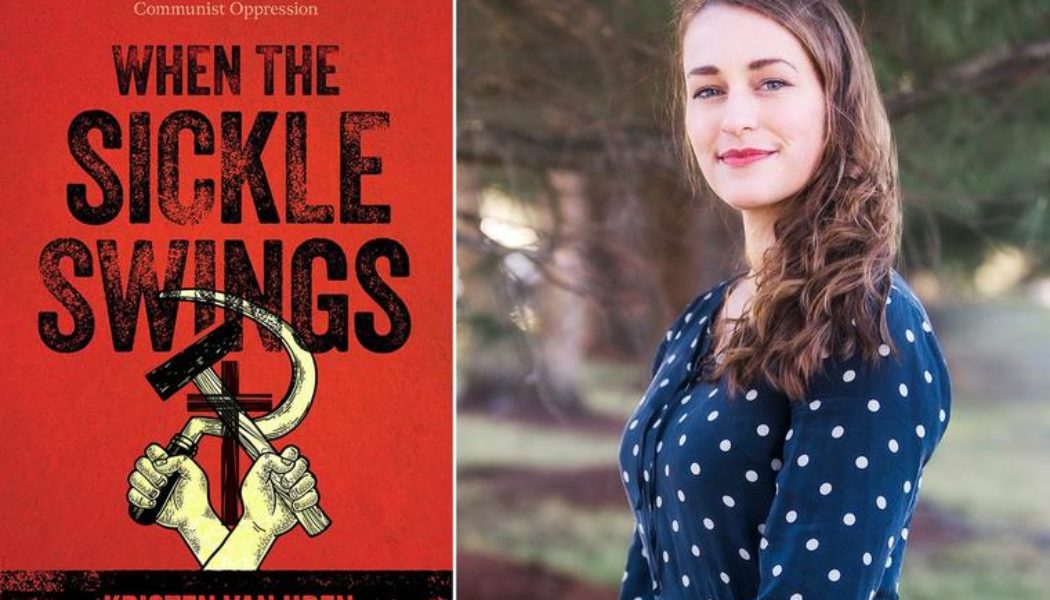

To try to comprehend why this is, meet Kristen Van Uden. She is editor of Catholic Exchange and a media spokeswoman for Sophia Institute Press. With degrees in history and Russian area studies, she is trained in oral history techniques, which she uses to preserve the stories of Catholic survivors of political repression. Recently, she edited the essays for When the Sickle Swings: Stories of Catholics Who Survived Communist Oppression. She is also, perhaps crucially, a millennial.

“Communism has always been a very seductive system,” she begins when asked why communism is attractive to young people today. “It promises earthly perfection and cloaks itself in the language of justice,” she adds, before going on to suggest that it promises not just a future of prosperity, but “a totalizing ideology that is greater than oneself.”

She reckons that in today’s world, where there is a climate of economic and social uncertainty, along with spiritual disorientation, “that message has again become attractive.” At the same time, she says, “we have to contend with decades of willful ignorance about the fruits of communism.” She points to many academic studies of history that “do not cover the causality between the ideas of Marx and Lenin and the suffering of millions, leaving generations of students naive to communism’s dark legacy.”

So, is the youthful attraction for the most part a case of historical illiteracy?

“Historical illiteracy plays a large role,” agrees Van Uden, “but the problem is ultimately spiritual in nature. In a hubristic mindset reminiscent of the Tower of Babel, communism offers heaven without the cross and attributes godlike powers to mere mortals.”

That said, she does not see a greater historical literacy as “a fail-safe panacea” to the current infatuation with socialism. “We all know well-educated university professors who are supporters of communism,” she continues. “Ironically, devoted communist ideologues, who pride themselves on their immunity to the ‘opium of religion,’ who reject empirical evidence of communism’s failure, while selectively interpreting history. Therefore, education of the facts is a defense, but education of first principles is the true antidote.”

In that case, When the Sickle Swings seems to be a timely antidote to the current revisionism. Is that why she wrote it?

“I was inspired to write my book by the urgency of memorializing a period that is expedient to forget,” she explains. “As I say on the back cover, ‘for nearly half of the twentieth century, across nearly half the globe, the Catholic Faith was repressed, restricted, or made illegal outright.’ While it sounds hyperbolic, this is an accurate description of communist regimes’ treatment of the Church. If this perspective shocks readers — and it should — it speaks to the necessity of recording these stories both for the historical record and as a testimony to the martyrs.”

Therefore, for a contemporary audience, what can her study of the communist persecution of Catholics teach? “The greatest takeaway from my interviews is a message consistent across diverse temporal, geographic and cultural landscapes. It is that the primary battle waged by communism is the war for souls,” she says.

Van Uden suggests that several stories in the book illustrate “the purportedly materialist regimes’ targeting of souls in the state of grace.” And, in so doing, she says, “reveal the [regimes’] ultimate demonic puppet master.” And so, while her book deals with a broad sweep of historical events, she maintains that the survivors she interviewed all “emphasized that political victories (or failures) pale in comparison to the cultivation of grace in the soul under regimes that actively sought to corrupt and steal souls.”

Seven years after the events in Russia of 1917, and with 15 million dead on account of the war and famine the revolution unleashed, the architect of all this lay dying: Lenin was 54 years old; he was suffering from a blood condition.

Initially, at least, when Lenin died, Jan. 21, 1924, Soviet leaders opposed the idea of preserving his body. However, as the crowds flocked to pay their respects to the corpse of the dead revolutionary, and sensing the propaganda possibilities, the same Soviet leaders had a change of heart. They agreed to try an experimental embalming technique developed by anatomist Vladimir Vorobiev and biochemist Boris Zbarsky.

And so began the Soviet and later Russian 100-year-old quest to preserve the body of one of the fathers of the revolution. During the 20th century, generations of Russian scientists fine-tuned the preservation techniques necessary to keep Lenin’s corpse as pristine and supple as any saint’s incorrupt body. Lenin’s Mausoleum in Moscow’s Red Square, since its opening in 1924, is where the body has been housed, and it has become the equivalent of a Soviet “Church of the Holy Sepulchre.”

Even with the fall of Soviet Communism in 1991, the mausoleum and what it contains was, and still is, maintained, as, to this day, the crowds come. Why this should be so remains almost as much of a mystery as what exactly it is those same crowds behold on entering the tomb.

From photographs, Lenin’s corpse would not look out of place in any waxworks museum. As it happened, shortly after his death, much of Lenin’s remains were removed at his autopsy; the remaining internal organs have all long since decayed, leaving what exactly is on display unclear. But then Lenin’s Mausoleum is about something Lenin and the other revolutionaries who met in a London church in 1907 despised, namely, a reverence for sacred relics.

Yet, today, the crowds still join the line to file past the tomb of Lenin, with the “body” inside that mausoleum held together by a combination of chemical agents too numerous to list. Ironically, these crowds come to make a pilgrimage to a man who was a convinced atheist.

It may have been in a London church in which the communist revolution was planned, but the religion that Lenin despised has, today, some 20 centuries later, no tomb for its namesake, or, more correctly, none that contains mummified remains — because Christians believe in a God who escaped the tomb, in One who, rather than bringing death to millions, brought the promise of eternal life to those who would but eat his Body and drink his Blood.