By Jay Nies

SCROLL THE ARROWS to see more photos.

Nate Pfenenger took his chances, rolled the dice and came out a winner.

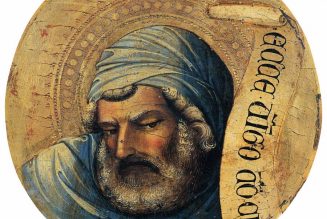

Specifically, he turned 20,400 black dice into an intricate, larger-than-life-size mosaic portrait of Venerable Father Augustus Tolton.

“I didn’t think it was going to be a big thing,” said Nate, a senior at Fr. Tolton Regional Catholic High School in Columbia. “I just thought it would be a really fun and memorable art project.”

Never one to settle for the ordinary, Nate says all of his art projects are “out of the box,” or beyond the scope of everyday thinking.

“I’ve used Rubik’s Cubes to make a mosaic of my dog,” he said. “I’ve made a bonsai tree out of twisted wire. I’ve painted cartoon characters on a pair of shoes. And now, I’ve made a mosaic out of dice.”

In search of his latest challenge, he recalled seeing several images that were created with dice.

He talked to his art teacher, Lonnie Tapia, who suggested he use this unusual medium to capture Fr. Tolton, a Missouri native born into an enslaved family, who grew up to become the first recognizably Black, Roman Catholic priest in the United States.

“Mr. Tapia gives his students so much freedom,” Nate noted. “As long as it qualifies as art, he’ll pretty much let you do it, within reason.”

Nate went into the project not knowing whether he would ultimately succeed with it.

“You do still learn something from failure,” he noted. “In life, too, it doesn’t mean you should give up if you fail at something. You use it as a stepping stone to future success.”

His first big challenge for this work was to acquire enough dice for the project.

“No store carries that many dice,” he noted.

He wound up ordering the dice from a wholesale distributor and having them shipped from China.

“And then, they got seized by U.S. Customs two or three times,” Nate noted. “That was quite the experience.”

He got some funny looks while buying 112 bottles of Super Glue, spread out across several stores in Columbia.

“Turns out, whenever you go buy 30 or 40 tubes of Super Glue at the same time, people’s first thought isn’t that you must be making a big dice mosaic,” Nate pointed out. “So, I did get some weird looks.”

He bought black dice with white dots, which worked well for illustrating Fr. Tolton’s dark skin.

He chose to reproduce perhaps the most familiar image of Fr. Tolton so that everyone, especially his schoolmates, would recognize him.

His parents agreed to cover the cost of the materials.

Planning and logistics were essential for the project.

“Once I developed my own system for how do to it, my system worked,” he said.

He used a computer image-generator to create the pattern for the mosaic.

He then set about learning the shades of each face of the dice.

“The No. 1 side is going to have the least amount of white, so it’s going to be the darkest color, going up to six, which is going to have the lightest color,” he said.

“And so you eventually just paint in with dice, in a sense,” he said.

He broke the pattern down into barely recognizable sections of 100 dice apiece.

He held the dice in each section together with blue painter’s tape, then marked the section in relation to where it would go in the finished work.

He created the sections during his art period and during his study period each day, then took them home and glued them together to a thick sheet of medium-density fiberboard (MDF).

“I drew up a grid of all the sheets of 100, and I assigned each one its own code, based on the row and numbers,” he recalled.

“So, I put like a serial number on the back, with a notation, so I’d know where that section fits into the pattern.”

He was surprised to hear that his system was similar to how Old World artisans in Italy created and shipped in sections the mosaics that were installed last year in the Cathedral of St. Joseph in Jefferson City.

He said he’s grateful that he had no mishaps or injuries, in light of the quantity of heavy-duty adhesive he was using.

“I don’t know how it happened, but I didn’t even get any of it on my fingers,” he stated.

He estimated that between planning and project, gathering the materials, placing the dice in squares and gluing the sections into place, the project took about 200 hours to complete.

There was little glamour about actually executing the project.

“I won’t lie, there were days when it was kind of boring to work on and I kind of got tired of it,” said Nate.

But he never lost sight of how satisfying it would be to finish the work well.

The completed image weighs over 100 pounds.

“One thing I found funny was when I was working on assembling the final picture in the art room, everyone thought it was the art teacher’s work, not mine,” he noted.

“So, everyone was like, ‘Wow! Mr. Tapia brought in a new piece of art!’” he said. “And I was like, ‘No, I did that!’”

Nate said he started out not knowing much about Fr. Tolton’s life story.

“Now, going to a school that’s named after him, you do learn what kind of weight his name carries and his importance as a person,” he noted.

“And I did learn a bit more about him along the way, because I figured I should know something more about the person I was making,” he said.

Viewing the finished artwork is a lesson in balance and perspective.

“You have to step back to see it as an image of Fr. Tolton, and then when you get up close, you end up seeing the individual dice,” said Nate.

He noted that he mistakenly placed one of the die at a 90-degree angle in relation to where it was supposed to be in the finished work.

“If you look very carefully, you can find it,” he said.

Knowing where it is, Nate recognizes the misplaced die the second he looks at the image.

“It’s an imperfect art piece,” he stated. “But I think that’s where the perfection lies. Not everything is perfect, so I think there’s something kind of satisfying about it.”

Besides, Fr. Tolton’s life, right up to the moment of his death at age 47 of heat exhaustion, seemed anything but perfect.

Nor is the work of promoting unity and reconciliation among people who look different from one another anywhere near completed.

Nonetheless, Fr. Tolton is well along the path of being formally declared a saint.

Nate said he was surprised at how much attention the finished work has attracted, beginning with a post on the school’s Facebook page and continuing with articles in the Columbia Missourian and now The Catholic Missourian.

For other young artists thinking about taking on such a complicated project, Nate suggests lots of planning and coordination, along with patience and humor for dealing with the unexpected.

“Just like anything else in life, do your research, know what you’re getting into, and make sure you have the dedication to see it through to completion,” he said.

As for his grade, Mr. Tapia gave Nate a 100-percent score for the project.

“I’m happy about that,” said Nate. “Doing all that work to get a ‘B’ would be mildly unfortunate.”