COMMENTARY: Coronavirus is making all of us into philosophers.

The ancient philosopher Plato understood philosophy as training for death. That didn’t mean thinking morbid thoughts or giving away one’s earthly possessions. Instead, it meant focusing on what is ultimately important, given the fact that our time here is limited, and none of us is sure what death will bring.

In that sense, this new coronavirus is making all of us into philosophers. We are having to distinguish what is important from what isn’t — what is essential from what is accidental. The great unknown, including the threat of an unforeseeable death for ourselves and our loved ones, brings everything else into question. Yet our worry testifies to a number of truths.

First, we are all one flesh. A single Adam or Eve figure, in China late last year, contracted this pathogen to which we are all now susceptible. Anybody who has the virus has been near someone who was near someone else, all the way back to someone near the original infected person just a couple of months ago. World travel, having closed the distances between peoples, calls attention to the biological kinship that makes us all vulnerable and that makes nearness and distance so important.

Second, social distancing is inhuman. We are not alien or angelic beings that commune via telepathy. Rather, we are embodied beings. Our flesh is a powerful, irreplaceable means of our expression. Hugs and handshakes, as well as frowns and smiles, are natural to us. All this distancing is foreign to what we are.

Third, familial nearing is an opportunity. As we retreat from the world into our homes, we look across the table into the eyes of our loved ones as if for the first time in quite a while. Familial nearing is the flipside of social distancing. We’re discovering anew the significance of the hearth and the home, as we cook together, play together and withstand trials together.

Fourth, we do not live on bread alone. As we run out of toilet paper and our favorite food items, we might recall that even a satisfied consumer is going to be fundamentally unsatisfied as a human being. During this time of bodily distancing, we would do well to draw near ourselves. Pick up and read long, absorbing books. Write thoughtful letters out by hand. Discover the power of words in the service of contemplating the truth about ourselves and our loved ones.

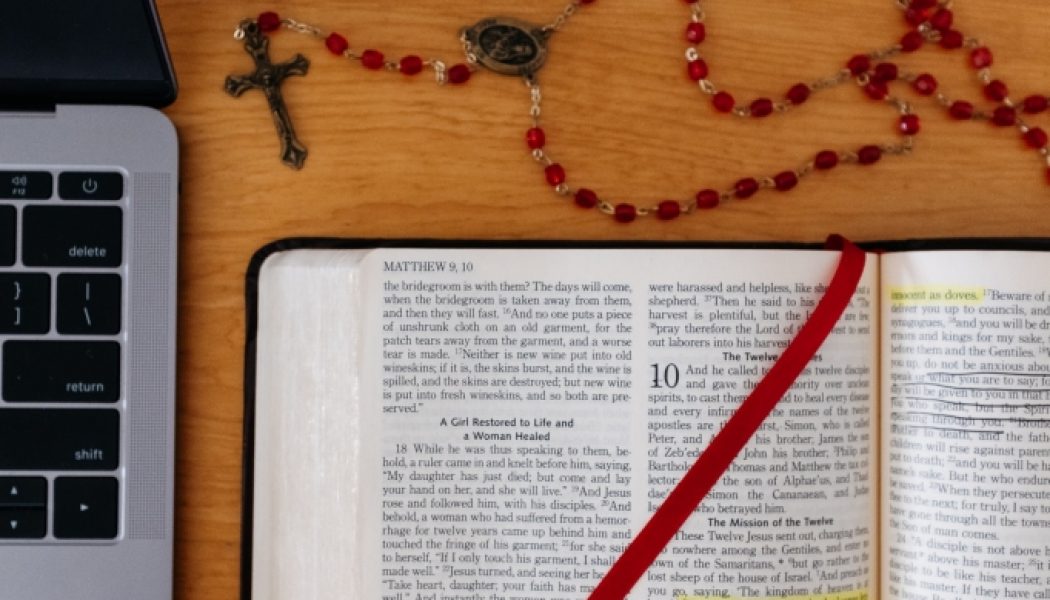

Fifth, what we live on is every word that comes forth from the mouth of God. The most unsettling aspect of social distancing is the fact that it keeps us from the reception of the sacraments, especially the Bread of Life. Yet Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger years ago wondered about this sort of situation: “Do we not often take the reception of the Blessed Sacrament too lightly? Might not this kind of spiritual fasting be of service, or even necessary, to deepen and renew our relationship to the Body of Christ?” Let us give voice to our hunger for God so that our prayer now will be touched with the desire that only bodily absence can bring and our next reception will be like the welcoming of a long-awaited friend.

Plato thought of preparation for death as a matter of distancing our souls from our bodies by means of disciplining our bodily passions. For Christian philosophy our preparation of death does not only involve taking control of our bodily desires — it also involves embracing our bodily being, how it unites us naturally and supernaturally to everybody but especially to those that are closest to us, our loved ones and, in particular, Our Lord. The present crisis underscores the Christian commitment to bodily being and our unique faith in the reality of bodily presence.

In Spe Salvi (Christian Hope), Benedict XVI observed, “Towards the end of the third century, on the sarcophagus of a child in Rome, we find for the first time, in the context of the resurrection of Lazarus, the figure of Christ as the true philosopher, holding the Gospel in one hand and the philosopher’s traveling staff in the other. With his staff, he conquers death; the Gospel brings the truth that itinerant philosophers had searched for in vain.”

To be a Christian means to train for death by living, in this life, the immortal life of God. It is by embodying friendship with the one who is the Resurrection and the Life that we will rise on the other side of death, no longer with the mortal body of Lazarus but with the immortal body of Christ. Social distancing might be the occasion for us to draw ever nearer to these truths of our lives.

Chad Engelland, Ph.D., is associate professor of philosophy and chairman of the philosophy department at the University of Dallas.

He is the author of Word Learning and the Embodied Mind (MIT Press, 2014) and The Way of Philosophy: An Introduction (Cascade, 2016).