/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/dmn/B3NGUJILBCTQ6BSZWVM3A6U5TU.jpg)

Among the peculiarities marking the pontificate of Pope Benedict XVI is the fact that he neither condemned nor ignored one of the most influential German philosophers of our era, Friedrich Nietzsche, the one who famously proclaimed the death of God in our times.

In the first and most moving encyclical of his pontificate, Deus Caritas Est (God Is Love), released on Christmas Day in 2005, Benedict unpacked the significance of divine love in relation to human desire, or what the Greeks call eros. To do so, he quoted an aphorism from Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil: “Christianity gave Eros poison to drink; he did not die of it but degenerated — into a vice.”

According to Nietzsche, Christianity ruins what is highest in us, the jubilant celebration of life that is erotic desire, by infecting it with guilt and sin. Because Christianity is in its essence opposed to life, it is no wonder that its God is now dead to us.

Pope Benedict, like St. John Paul II before him in the Theology of the Body, took seriously the thought that sexual desire is the apex of human nature, but he pointed out how naive Nietzsche was.

Sexual love is a blessing if and only if it is purified, if and only if it becomes transfigured by a love that seeks to bless rather than a love that simply seeks to consume. Lust is no liberation but a domination and enslavement for all parties that are involved in its desperate clutches.

In this way, sexual desire becomes a celebration of life only if it is transfigured by the love of God that liberates us to seek the common good. God’s love fills us and frees us to give to others rather than to take from them. In this way, Benedict shows that Nietzsche was only half right. The full truth is that Christianity gives Eros medicine to drink, which heals him of his infirmities and makes him healthy and strong, a veritable image of the true God.

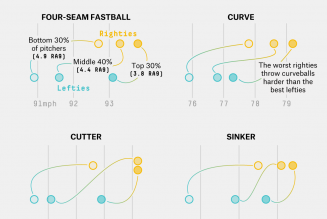

Not only did Benedict dialogue with Nietzsche but with the limits of modernity. In the oft misunderstood Regensburg Address, for example, he argued that we cannot enter into dialogue with Islam’s view of God because the modern West has truncated reason to but a shadow of its former splendor, applying it only to what can be empirically measured and quantified. But in the ancient and medieval world, reason could also talk about God as the first and ultimate cause of all things. Benedict challenged the West to recover the original reach of reason so that dialogue about God can happen among Christians, Muslims and all people of goodwill. We need not resort to violence to settle our differences, for reason can indeed mutually illumine.

The pope was a theologian who, like the church fathers of old, stuck resolutely to the essentials of the faith and in this way dialogued with the deepest desire of our hearts, a desire he knew craves the presence of the God that is love. His earlier work editing the acclaimed Catechism of the Catholic Church and his personal theologizing testify to this single-minded clarity concerning what really counts.

In the three-volume Jesus of Nazareth, published while he was pope but in his capacity as a theologian, he wrote that Jesus did not bring any new ethical principles but instead ratified the existing ones. What Jesus freshly and newly brought into the world is the very face of God, the localized personal presence of the origin of the world, the creator who creates all things and does so to bless them with life.

For if the death of God is the death of our deepest desire, the rebirth of God, through recovery of the greatness of reason and the encounter with the living God, is our highest affirmation.

As he said in his first homily as pope, in words that spoke directly to so many of us: “Only when we meet the living God in Christ do we know what life is. We are not some casual and meaningless product of evolution. Each of us is the result of a thought of God. Each of us is willed, each of us is loved, each of us is necessary.”

Pope Benedict is dead. May he rest in peace, and may his witness to the living God continue to fill our thoughts and hearts with the bounty of personal love.

Chad Engelland is professor of philosophy at the Rome campus of the University of Dallas and author of several books. He wrote this for The Dallas Morning News.

This column is part of our ongoing Opinion commentary on faith, called Living Our Faith. Find this week’s reader question and get weekly roundups of the project in your email inbox by signing up for the Living Our Faith newsletter.

We welcome your thoughts in a letter to the editor. See the guidelines and submit your letter here.