When Tyge O’Donnell found out he would have the opportunity to meet Pope Francis, he knew he had to present him with a gift he’d remember.

Then the Las Vegas resident remembered that the pope, known to be a lover of team sports, had been given a Vegas Golden Knights jersey with his name on it last season by the team’s investor and legal consultant Tim Busch.

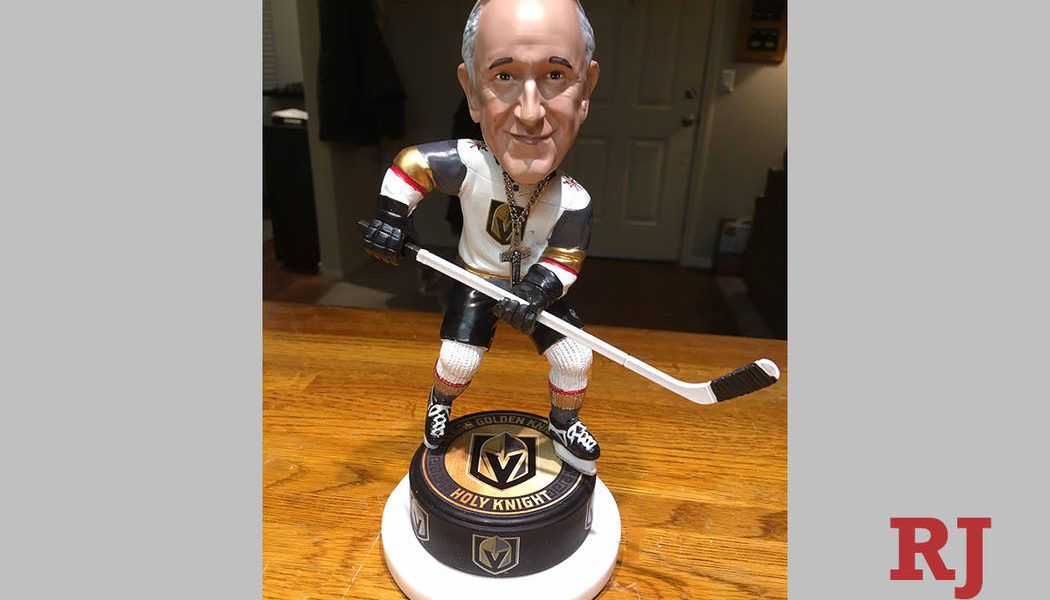

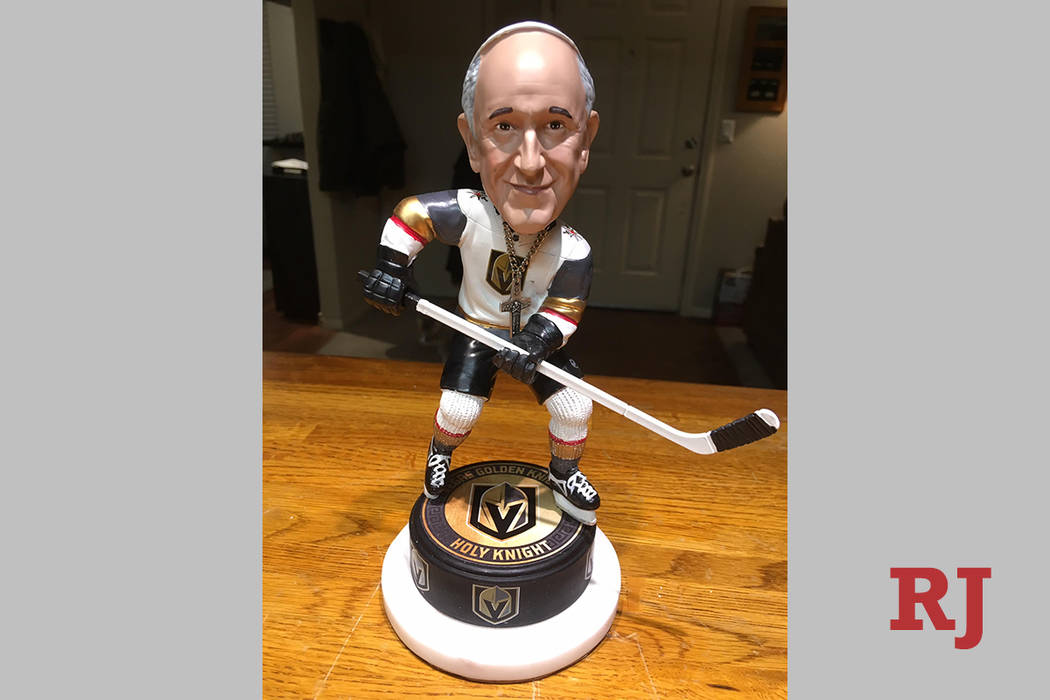

So O’Donnell went out and bought two bobbleheads — one of Golden Knights forward William Karlsson and one of the pope.

With a bit of careful prying and gluing, he managed to swap their heads and created a custom bobblehead of the leader of the Roman Catholic Church wearing a “zucchetto” — the conical clerical cap he favors — but clad in a Golden Knights jersey, holding a hockey stick in his hands and standing on a puck. Then, with the help of the team’s graphic artist, he added the words “Holy Knight” on top of the puck.

Tragic backstory born of war

O’Donnell presented the gift to the pontiff on Nov. 24 at an event in Nagasaki, Japan, one that O’Donnell was invited to attend not to talk sports but to pay tribute to the pope’s role as a champion of world peace.

There is a tragic backstory to this lighthearted moment, one that began years earlier when O’Donnell’s late father, retired Army Sgt. Joe O’Donnell, pulled out some photos he had taken while working as an Army Air Forces photographer during World War II that had long been stored in his attic.

Some of those photos were later donated to a museum in Japan, published in a book and featured in at least one published article.

It’s not clear where Francis saw them, but one photo, taken in Japan in September 1945 after the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end World War II, caught his attention.

The photo, “Two Brothers at Cremation Site,” shows a boy, waiting his turn at a crematory, carrying the lifeless body of his younger brother on his back.

Francis reprinted the photo and a year ago began passing it out at Mass with the words “The fruit of war” written in various languages.

At the event at Nagasaki Peace Park on Nov. 24, the pope called on the world to abolish nuclear weapons. Braving the rain, a crowd of about 1,000 stood where on Aug. 6, 1945, an atomic bomb had decimated the city. Francis later visited a local stadium and celebrated Mass for 35,000 people.

His was the first visit to Japan by a pope in 38 years.

‘Picture has contributed to peace’

In the short one minute and 45 seconds he spoke to the pope, O’Donnell thanked him for using his dad’s photograph to promote his message.

“He said, ‘The picture has contributed to peace,’ ” O’Donnell said.

During his trip, O’Donnell also visited the site where Japanese scholars believe his father’s photo was taken. The spot on a steep hill and in the woods, but with a clear view of the city below. On the day he visited, it was quiet save for the sounds of the birds and trees blowing in the wind.

“As sad as it is, it’s a very peaceful final resting spot,” he said.

O’Donnell, 50, a bellman at Caesars Palace and a photographer for LVSportsBiz.com, said 45 of his father’s photos, including the one of the boy, were donated to a Japanese museum 10 years ago.

He remembers his dad, who died in 2007 at 85, describing the boy’s emotions as he watched the men running the makeshift crematorium take his brother’s body and lay it in flames.

“He said some men came over, grabbed the brother off the boy’s back, and threw him in flames. He just stood there and bit his lip so hard it bled,” O’Donnell said. “He wanted to go over there and hug the kid and comfort the kid, but he was afraid they’d both break down.”

After his time in the service, the elder O’Donnell was a photographer for the White House during the administrations of Presidents Harry Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon.

After returning to the states, he kept the negatives of his personal pictures from the service in trunks in the attic. He told his family never to touch the trunks, and that’s where they stayed for 45 years.

‘Locked away’

“He just kept it bottled up, locked it away,” Tyge O’Donnell said. “This is what happens when you have war, you get children victims.”

But in 1989, Joe O’Donnell, suffering from depression not only from the memories but from recurring health problems, went on a religious retreat at the Sisters of Loretto Motherhouse in Kentucky.

“My dad said he often wondered why he had been spared when so many others were killed,” Tyge O’Donnell told the Las Vegas Review-Journal in 2007.

“On the retreat he saw this sculpture of a man created in honor of the victims of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. He decided that this meant he was spared to use his experiences to prevent nuclear war.”

He returned home to Nashville, Tennessee, and decided that he would put a traveling photo exhibit and book together, “Japan 1945, Images From the Trunk,” which was published on the 50th anniversary of the bombings.

In 2005, Joe O’Donnell wrote an article for American Heritage magazine.

In it, he described his experiences in the aftermath of covering the bombing.

“Years later, many years later, the nightmares began: the voices of the children, the endless stretches of rubble and bone, the stench. Over and over again. The voices were always pitiful, always begging. Yet they were accusing, too.”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @ByBrianaE on Twitter.