Why do “former Catholics” make up 10% of America’s population?

Why do some children raised Catholic stop practicing the faith, while others continue going to Mass as adults?

For parents who want to raise Catholic kids, there may be few questions more important.

And it turns out there are factors which can help predict whether children raised Catholic continue practicing the faith as adults, according to The Pillar Survey on Religious Attitudes and Practices, which we present this week in a series of reports.

Those factors include attending Catholic school and going to Mass weekly. But there are others as well. Just one example: our survey showed a high correlation between praying grace as a family, and going to Mass weekly in adulthood.

In part one of this series, The Pillar looked at America’s changing religious landscape. In part two, we look at what factors influence lifelong Catholic religious practice, why people say they leave the Church, and whether Catholics recently immigrated to the United States paint a different picture than other Catholics.

Some results surprised us.

Is demography destiny?

Of course, asking questions about the future of the Catholic Church should begin by recognizing some stark demographic trends — which The Pillar examined using data available from CARA, the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate.

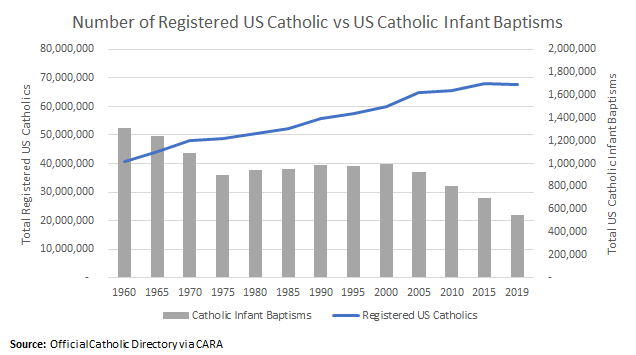

Since 1960, even while the total population of Catholics registered in U.S. parishes has increased by 66%, the number of infant baptisms per year has dropped by 58%. Those numbers indicate a Church growing through immigration and longer lifespans, but in which the younger generations of Catholics are smaller than the older ones.

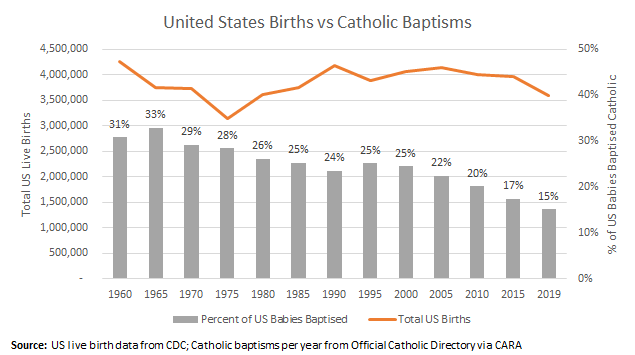

Comparing the number of infant baptisms performed by Catholic parishes to the number of live births in the US, as recorded by the CDC, paints a similar picture. In 1960, 31% of the children born in the United States were baptized Catholic. By 2019, that number was down to 15%.

It seems a fairly clear conclusion that if only 15% of children in the US are baptized as Catholic, the Church can not expect to be 24% of the U.S. population in the near future, at least without an unforeseen conversion trend.

A declining number of baptisms might suggest an aging church abandoned by young families.

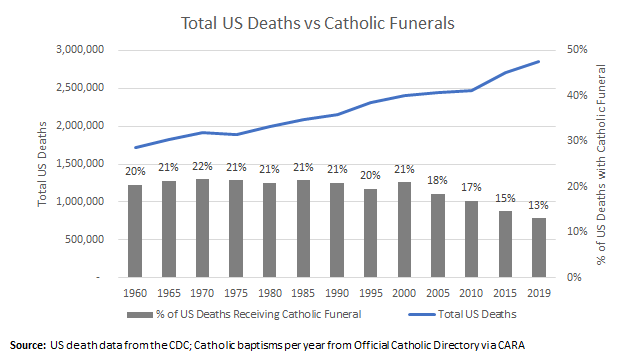

But disaffiliation is not only a phenomenon among the young. The total number of Catholic funerals peaked in 2000 and has since fallen 25%, even as the total number of deaths in the U.S. has continued to rise. While 21% of U.S. deaths received a Catholic funeral two decades ago, today only 13% of them do.

Whether it is the choice of the deceased or of their surviving children, a growing number of people are not returning to a Catholic church, even when it’s time to be buried.

In order to better understand these trends, we asked people in our survey about their religious identity or affiliation, and about the primary religious affiliation in which they were raised.

In our representative national sample, we found that 24% of respondents currently consider themselves Catholic. An additional 10% of respondents were raised Catholic but no longer considered themselves members of the Church.

We aimed to find out what the Church can learn from those who left, and those who didn’t.

Here’s a technical paragraph, if you’re interested in that kind of thing: Our survey was conducted by research firm Centiment. In addition to our representative national sample, we collected an oversample of current and former Catholics, which provides us with 1099 total respondents who were raised Catholic and still identify as Catholic, and 426 who were raised Catholic but no longer consider themselves Catholic. Those numbers give us a 3% error margin when discussing current Catholics, and a 4% error margin when analyzing trends among former Catholics. You can read more about our methodology in part one of our series.

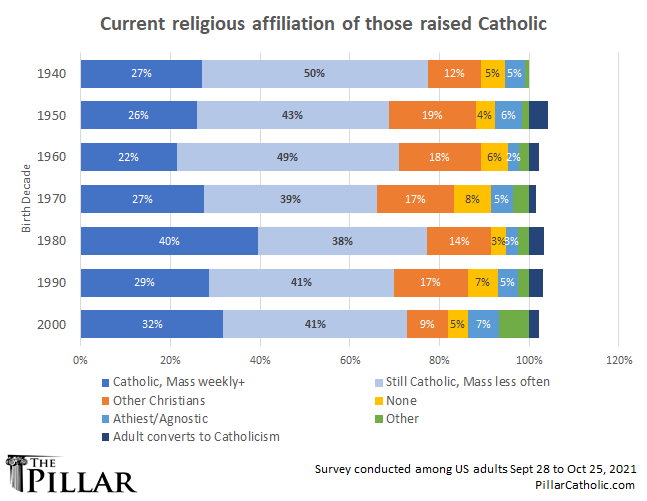

Here’s the big picture: Catholics born in the 1950s through the 1970s are the least likely to still identify as Catholic. Among those who do identify as Catholic, respondents born then are also less likely than other generational cohorts to attend Mass weekly.

Among people between 42 and 71 years old, 69% percent of those raised Catholic still identify as Catholics today.

But among people 41 years old or younger, 73% of those raised Catholic still consider themselves part of the Church.

Twenty-five percent of Catholics between 42 and 71 years old attend Mass weekly, while 33% of adult Catholics 41 or younger attend Mass weekly.

Those born in the 1980s were the most likely (77%) to remain Catholic and the most likely to go to Mass at least weekly.

The ‘domestic Church’

For many Catholic parents, it is both satisfying and terrifying to consider the responsibility that comes with raising a child to know, love, and practice a faith for the whole of life. But what elements of family life have an impact on religious practice? We wondered if we could find out.

Our survey asked respondents about their family’s religious activities when they were school-aged children and teens.

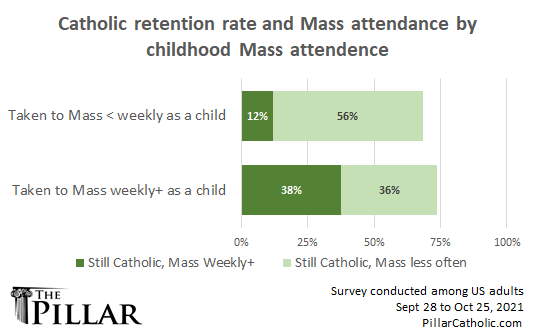

Children taken to Mass at least weekly were only 6% more likely to identify as adult Catholics (74% vs 68%).

But Catholics who went to Mass weekly as children were far more likely to attend Mass as adults than people who did not. Thirty-eight percent of Catholic adults who were taken to Mass at least weekly as children continue going to weekly Mass as adults. Among Catholic adults who were not taken to Mass weekly as children, only 12% go to Mass as adults.

Parents feeling badly about not taking their children to daily Mass need not fret: There is not a significant difference in adult Mass attendance between those who were taken to Mass daily as children and those taken weekly.

The Pillar brings you smart, faithful, independent news about the Catholic Church — when we report news, it makes a difference. We can’t do it alone. Become a paying subscriber now:

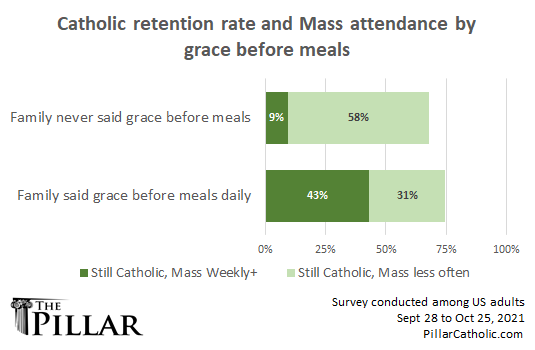

There are some seemingly small family practices which proved to show significant differences in the habits of adults raised Catholic.

Catholics who grew up daily saying grace before meals are 34% more likely to go to Mass weekly than other Catholic adults.

It would be a mistake to attribute that entire difference to the frequency with which people said grace before meals. It is instead likely that this difference of family practice is a marker for a way of life in which faith is practiced in a more everyday fashion.

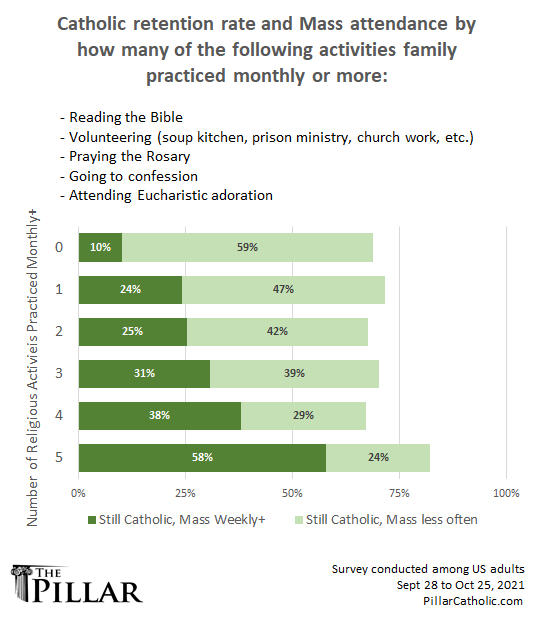

Our survey also asked about the frequency with which respondents’ childhood families participated in various Catholic devotions or practices.

Five showed a clear correlation between childhood practice and regular Mass attendance later in life:

-

reading the Bible.

-

volunteering (soup kitchen, prison ministry, church work, etc.).

-

praying the Rosary.

-

going to confession.

-

Eucharistic adoration.

People who reported that their childhood families had participated every month in all five practices had an 82% chance of remaining Catholic and a 58% chance of going to Mass weekly later in life.

People whose families participated in some of these activities showed average rates of remaining Catholic, but above-average rates of weekly Mass attendance.

Among those who said they participated in none of those activities as children, 69% still consider themselves Catholic, but only 10% attend Mass weekly.

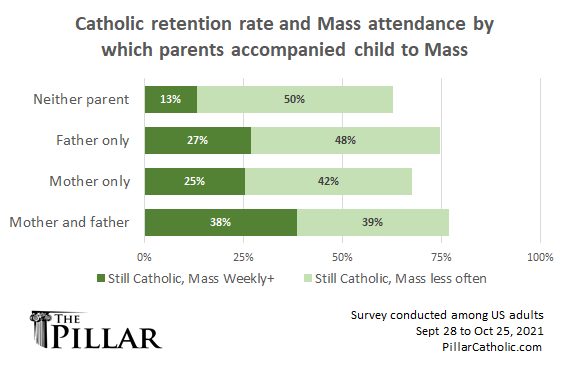

We also found that children whose parents attended weekly Mass with them were more likely to identify as Catholic or attend Mass as adults.

Respondents who went to weekly Mass but were not accompanied by either parent were less likely to identify as Catholic attend weekly Mass as adults than those accompanied by one or both parents.

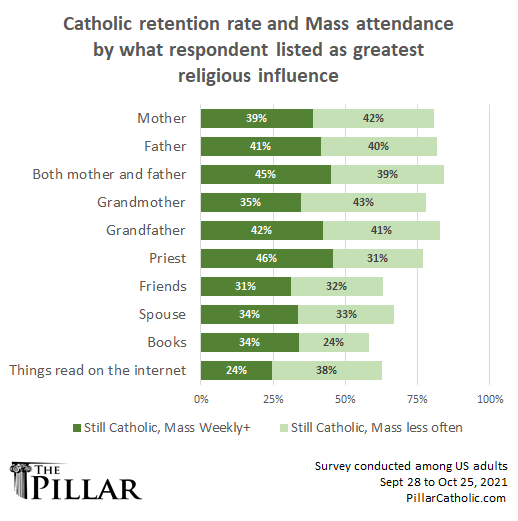

Finally, we asked people “What influences have had the greatest effect on your current religious beliefs and practices?”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, people who listed their mother and father as their biggest influences were some of the most likely to still be Catholic and to go to Mass frequently. Grandparents and priests were also strong positive influences correlated with continued Catholic practice. And — offering a note of humility for those of us who live by the written word — respondents who listed books or things read on the internet as their greatest religious influences were among the least likely to remain Catholic or to go to Mass weekly.

Paying subscribers ensure that everyone — those who can pay and those who can’t — can read The Pillar. Help make sure our work is available to the entire Church. Become a paying subscriber today:

Catholic education

Catholic schools have a unique place in the history of the Church in America. We wanted to understand whether attending Catholic schools correlated to adult Catholic identity and practice.

We asked all respondents in our survey what types of school they had attended. The question allowed them to check all types of school that applied, so the data includes all respondents who had attended Catholic schools for any part of their academic career.

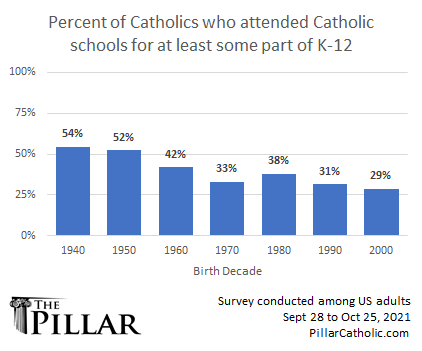

We found that the percentage of Catholics who had attended Catholic schools fell over time. More than half of Catholics born in the 1940s and 1950s attended Catholic schools, but only about 30% of those born in the 1990s and 2000s did so.

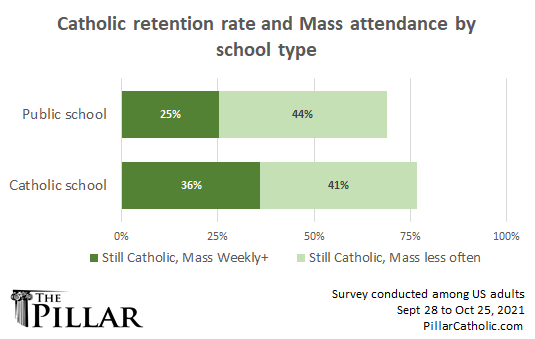

We collected data on all types of schools, but only Catholic schools and public schools had enough attendees to draw useful conclusions. Seventy-seven percent of those who went to Catholic schools still consider themselves Catholic, while only 69% of those who went to public school do.

We tried controlling our data for childhood Mass attendance, family religious practices, etc. — But in all cases, we found a clear difference, in both adult Catholic identity and weekly Mass attendance, between people who went to Catholic schools and their public school counterparts.

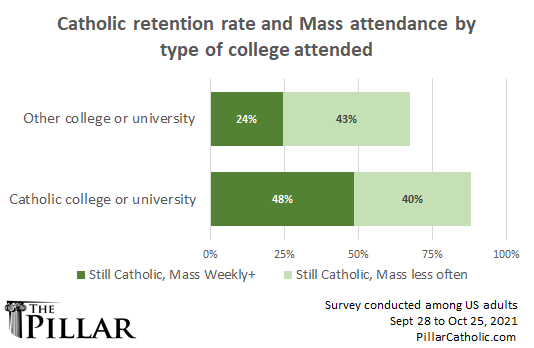

We also asked respondents whether they had attended a Catholic college or university. Among respondents who went to college, 30% of those raised Catholic went to a Catholic-affiliated college or university. Those who went to a Catholic college were 23% more likely to remain Catholic and twice as likely to attend Mass weekly as those who did not.

The apparently significant impact of attending a Catholic college might seem surprising. But survey data might offer an explanation.

Elsewhere in the survey, we asked respondents if they had ever stopped attending religious services for a period of more than a year, and if so, at what age they had done so. Twenty-five percent stopped going to Mass in high school, 13% did so in college, and 19% in their 20s.

Seventy-four percent of respondents who stopped going to Mass for a year or more did so during their teens or 20s.

Perhaps in addition to opportunities for spiritual and intellectual formation, Catholic colleges simply offer more opportunities for students to attend Mass regularly, keeping up the habit.

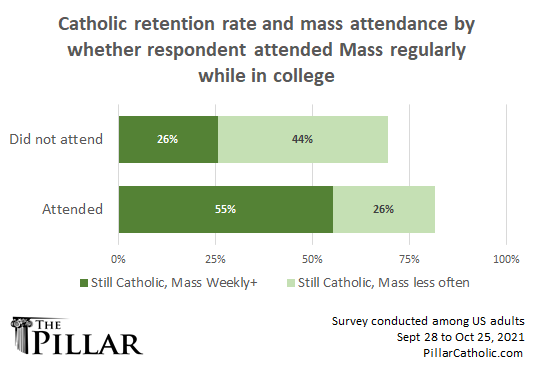

We also asked respondents whether they had participated in various religious activities during college, including whether they regularly attended religious services. Among Catholics who attended college, those who regularly went to Mass while in college are more than twice as likely to be weekly Mass goers now, and 12% more likely to still consider themselves Catholic.

The immigrant experience

When the demographics of American Catholicism are discussed, people often ask whether immigration is “propping up” the number of Catholics in the U.S., as native-born Catholics are heading for the exits.

We asked respondents whether they were born outside the U.S. and also whether one or both of their parents were born outside the U.S.

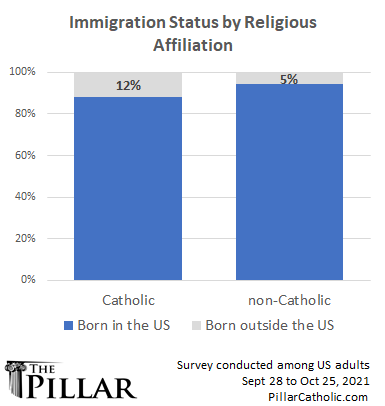

Overall, 7% of the respondents in our nationally representative sample were born outside the United States. Slightly more that half of those are Catholic. This means that immigrants are more heavily represented among Catholics than among non-Catholics.

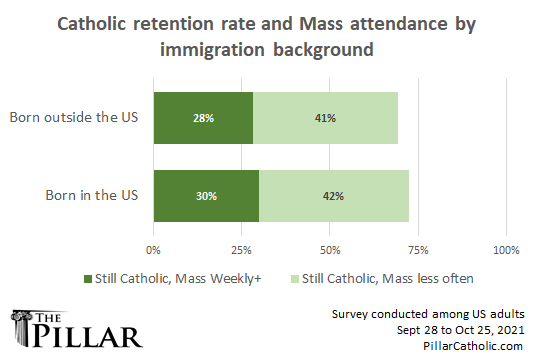

Catholic immigrants are much the same as Catholics born in the U.S., at least in terms of how likely they are to remain Catholic, and how likely they are to attend Mass weekly or more.

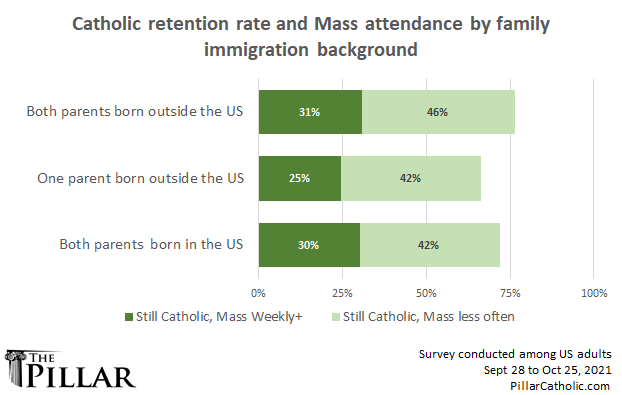

Americans with both parents born outside the U.S. are very similar to respondents with parents born in the U.S; people with one parent born outside the U.S. and another born in the U.S. were slightly less likely to remain Catholic or attend Mass weekly. Given that the immigrant samples in our survey are fairly small in number, the data may be impacted by outliers.

Why people leave

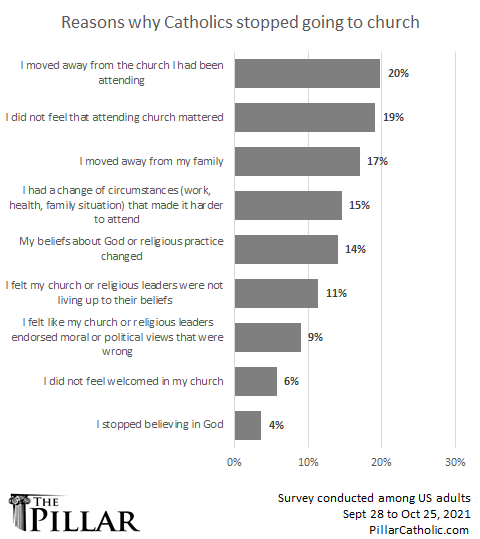

We asked our respondents “If at some point you ceased to attend religious services regularly (for a year or longer) why did you do so?”

The results we received were a mix of theological issues and practical ones. Of the top four, three are practical issues.

The most common reason, cited by 20% of people raised Catholic who stopped attending Mass for a year or more, was: “I moved away from the church I had been attending.”

The second-most common response is more theological: “I did not feel that attending church mattered.”

The next two most frequent reasons for ceasing to attend Mass for a time are practical: “I moved away from my family” or “I had a change in circumstances that made it harder to attend.”

Additional theological and moral reasons for ceasing to go to Mass were less frequently cited.

One implication of the frequency with which these mundane reasons were cited is that when someone moves away from the home of their youth, into a different culture, and perhaps far away from family and friends, that person is likely to experience a rupture in religious practice because for many people the habit of going to Mass and receiving the sacraments is a family and location-driven habit.

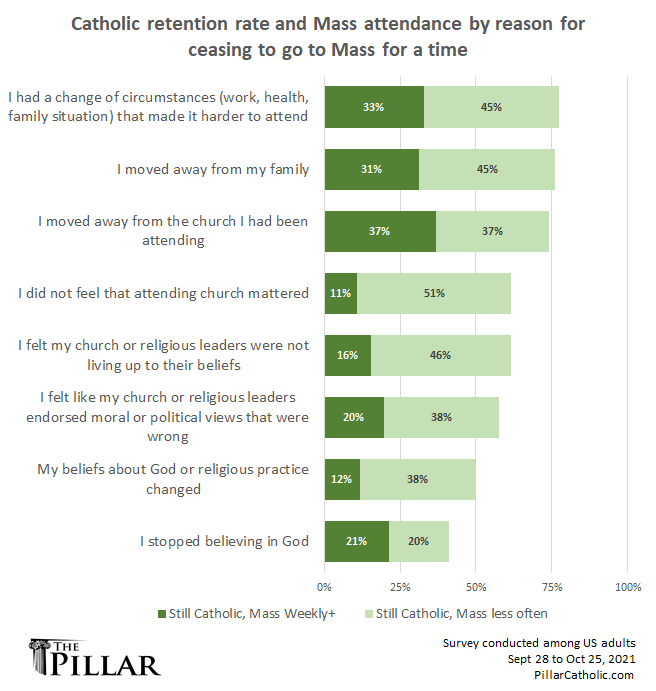

While both practical and theological reasons drive the decision to stop attending Mass, those who stopped for practical reasons were more likely to continue identifying as Catholic.

Those who stopped going to Mass because they stopped believing in God were the least likely to continue to identify as Catholic in the long term. Also very unlikely to identify as Catholic or to resume going to Mass were those who said their beliefs about God or religious practice had changed, or those who believe that their religious leaders had endorsed moral or political views that were wrong.

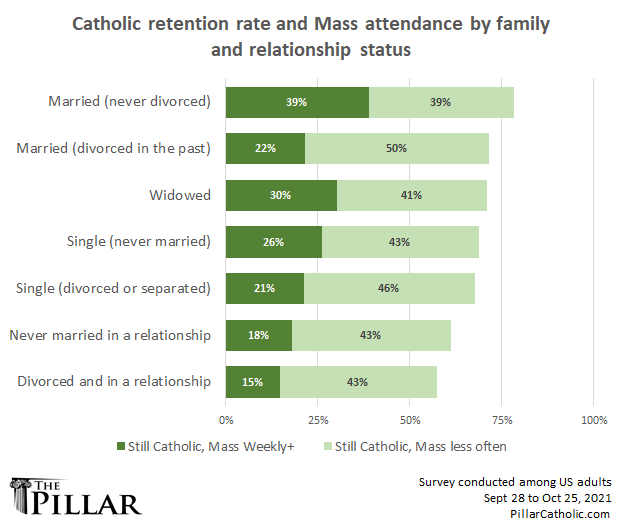

The Pillar’s survey also looked at whether relationship status impacted Catholic identity and Mass attendance. Among respondents raised as Catholic, we found that those who are married-and-never-divorced were most likely to identify as Catholic, while those who are divorced-and-in-a-relationship are least likely to identify as Catholic.

In the short term, many people who stop going to church do so because of a practical disruption in their lives.

But people who stop going to Mass and don’t resume are more likely to have theological issues with the Church, or relationships which put them at odds with Church teaching on marriage.

This points to two different paths which the Church must follow in order to minister to all of the baptized. At a practical level, the Church must find ways to reach out to those who become estranged from the Church for prosaic reasons like moving far from home or far from family. At the more theological level, however, the Church must also find ways to evangelize those whose beliefs or personal relationships might lead to longer-term disaffiliation.

Part one of this series brought you a look at overall trends in the American religious landscape. Part three will bring you a look at the “nones” — the growing number of Americans who say they have no particular religious affiliation at all.

Hey! You seem like a smart, reasonable, discerning consumer of news. So it’s time you become a paying subscriber to The Pillar:

And don’t forget to tell your smart, reasonable, discerning friends, too:

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity