SAINTS & ART: St. Charles Borromeo did more by age 24 than most do all their lives.

St. Charles Borromeo (1538-1584) was a key figure for Catholicism in the 16th century, even if he lived only to age 46. He was archbishop of Milan (one of the most important bishoprics in northern Italy), a cardinal, papal secretary of state and leader of the Counter-Reformation.

He started out with the equivalent of a 16th-century silver spoon in his mouth. His father was a count married to a daughter of the Medicis. His uncle was Pope Pius IV. Both probably out of familial religious commitment and because Charles was his second son and so not immediately in the line of succession, his father agreed to his receiving tonsure — admission to the clerical state — at 12. Charles began his studies (one of his professors was a cardinal) but his father apparently awarded him only a modest stipend that did not meet all the needs of him and his retinue. With his father’s death, Charles wound up taking over family business affairs and got his first practice in diplomacy: the family castle in Arona, It wasn’t so much a family squabble as a squabble between the Kings of France and Spain. Charles kept the peace. By 1559, he had his doctorate.

He was subsequently put in charge of administration of the Papal States. As Secretary of State, Borromeo restarted the Council of Trent, which had been interrupted for 10 years (1552-1562). (He also later had a major hand in the Catechism of the Council of Trent). Not bad for a 24-year-old!

By the way, we might note that, up to this point, Charles Borromeo had still not been ordained a priest. “Cardinal” is a title, as were the other administrative and managerial functions he exercised. His elder brother’s death caused him to decide between involvement in the temporal and spiritual worlds, and he chose the latter. On Sept. 4, 1563, he was ordained priest. On Dec. 7, he was consecrated bishop.

In 1564 he went to the See of Milan. Having begun some reform of the Roman clergy, Charles brought ecclesiastical reform to Milan with a gusto. He imposed clerical discipline, ended abuses, promoted education for priests in seminaries (a major Tridentine reform — previously, many priests were trained by “apprenticeship”), launched the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine to promote sound religious education and catechesis, convoked several provincial synods and demanded monastic reform. It was not received well in all quarters — some religious even tried to assassinate him.

He lived through the success of the Battle of Lepanto against the Turks. His sister’s father-in-law was commander of the papal ships.

In 1576, the plague broke out in Milan. Charles believed the plague was a chastisement for sin, and he intensified his prayer. Pastorally, it’s said he visited the homes of the sick and the hospital, setting an example for his less-zealous diocesan clergy. He led penitential processions, barefoot with a rope on his neck. By 1578, the plague was abating, and Milan built a votive church to St. Sebastian in thanksgiving for deliverance for the pandemic.

Charles continued a hectic pace of travel for the Universal Church to Rome and throughout his archdiocese (even to hamlets in the Swiss Alps) until his death, which came in 1584. It is said he died of erysipelas, a bacterial skin infection, which causes fever. It’s treated today by penicillin, but penicillin was unknown in 1584.

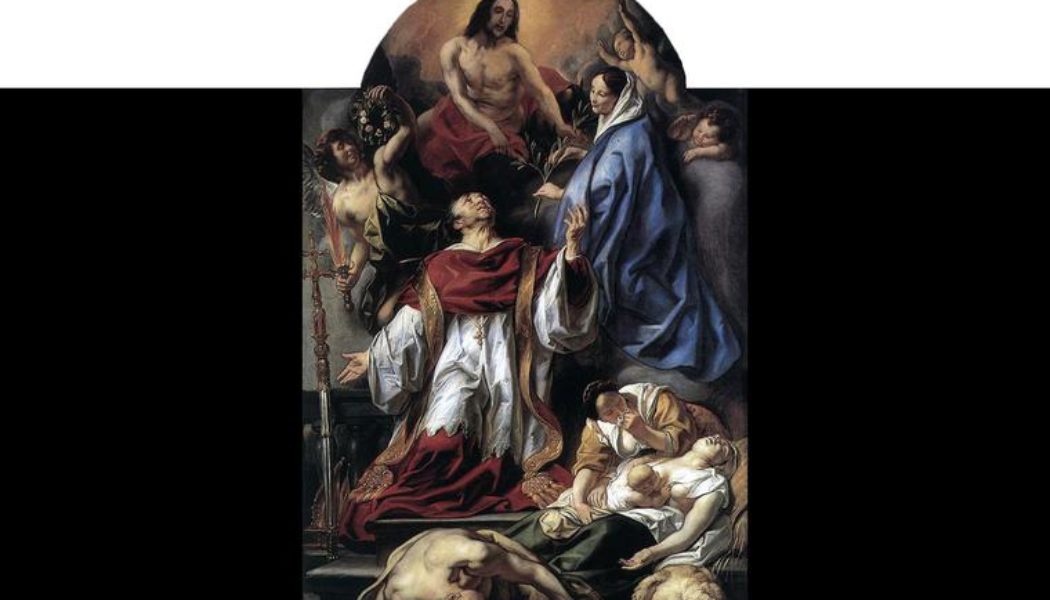

Flemish painter Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678) painted “St. Charles Cares for the Plague Victims of Milan” in 1655. It hangs in a church in Antwerp, Belgium.

Charles and the Blessed Mother are the dynamic figures linking heaven and earth. The posing of their bodies leads the viewer to and through them, up to Christ. Below them are the victims of the plague: a dead man, a dead sheep and a dead woman. Her baby still tries to suckle her breast. Another woman looks at the dead mother mournfully. Man and beast both suffer.

Charles, in full episcopal regalia, turns pleadingly to the Blessed Virgin Mary. His left hand appeals upward to her, his right indicates the victims below. Mary looks at her son, Charles, lovingly, while her Son, Jesus, looks lovingly at her. While the somewhat bare bodies at the bottom of the painting are lifeless, the somewhat bare angels and cherubs are full of life in the presence of God. The composition, forms and physiology of the painting make clear that it belongs to the Baroque, of which Jordaens was a master.

The painting is entitled St. Charles verzogt (“cares for”) the plague victims. The painting shows how exactly ecclesiastical field hospital workers should be “caring for” victims of pandemic: first and foremost by invocation of God’s mercy. But we also know from his life that Charles combined ora et labora — prayer and work — in providing spiritual and temporal care for the dying.

Charles may have enjoyed many benefits and privileges from his life situation, but he used them ad majorem Dei gloriam — “for the greater glory of God” — and the good of souls. There used to be a U.S. Army advertisement whose pitch line was, “we do more by 9am than most people do all day.” Okay, Charles did it by the time death closed his eyes at 46. If “Be All That You Can Be” is a motto for a Christian and not just the Army, Charles was a stellar example.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity