The final word on the legacy of John Fisher and Thomas More, and the final judgment (under God) on why we should see them as heroes, is given by G. K. Chesterton, a man who proves in his very self that the killing of More and Fisher did not kill learning, laughter or holiness: “There is this true relation between the martyr and the doctrine for which he died; that he died, not only defending the Pope, but defying the sort of man who wants to be Pope.”

O, how wretched

O, how wretched

Is that poor man that hangs on princes’ favours!

There is, betwixt that smile we would aspire to,

That sweet aspect of princes, and their ruin,

More pangs and fears than war or women have;

And when he falls, he falls like Lucifer,

Never to hope again.

—William Shakespeare

(From King Henry the Eighth)

In June 1532, displaying a courage that was sadly lacking in the rest of England’s bishops, John Fisher preached publicly against the king’s plans to divorce Catherine of Aragon. In January of the following year, the king secretly went through a form of marriage with Anne Boleyn, who was now pregnant. Two months later, Thomas Cranmer became Archbishop of Canterbury. A week later, Fisher was arrested. It seems that the king and Cranmer wanted Fisher out of the way so that he could not speak out publicly against the granting of the king’s divorce, which Cranmer pronounced in May, or the coronation in early June of Anne Boleyn, who was now six months pregnant. Bishop Fisher was released two weeks after the coronation, with no charges being made against him.

In March 1534, John Fisher was accused, along with Thomas More and others, of alleged complicity in the so-called treason of Elizabeth Barton, known as the Holy Maid of Kent, who had claimed to have had a vision of the place in hell reserved for Henry if he divorced Catherine and married Anne Boleyn. Dispensing with the formality of any trial, Parliament found Fisher and others guilty of the charge. Fisher’s punishment was the forfeiture of all his personal estate and imprisonment at the king’s pleasure. He was subsequently granted a pardon on payment of a fine of £300. The poor hapless “Holy Maid” was not so fortunate. In April she was hanged for treason, along with five of her associates, four of whom were priests. Her head was then severed and placed on a spike on London Bridge as a warning to any others who might be tempted to question the actions of the king. A year later, the heads of John Fisher and Thomas More would suffer the same grisly fate. In the words of historian Richard Rex, “[t]he execution of the Holy Maid and her companions was one of the many ways in which judicious use of judicial terror … was employed to secure compliance with the English Reformation.”[1]

In the same month in which More and Fisher had been arrested for their alleged involvement with the Holy Maid, Parliament passed the First Succession Act, a law which compelled all those called upon to do so to take an oath of succession, acknowledging any children from the marriage of Henry and Anne to be legitimate heirs to the throne. Failure to do so would be considered an act of treason, punishable by death.[2] John Fisher refused the oath and was imprisoned in the Tower of London on 26 April 1534. Two weeks earlier, Thomas More had also refused the oath.

It was from his prison cell in the Tower that More saw the abbot of the London Charterhouse and three other monks passing below his window on their way to meet a martyr’s death, chanting praises to the Lord as they went. Like More and Fisher, they had refused the oath. “These blessed fathers be now as cheerfully going to their deaths as bridegrooms to their marriage,” More exclaimed to his daughter.[3]

As news of the horrific and heroic deaths of these holy monks reached them, John Fisher and Thomas More must have reflected grimly on what awaited them if they continued to refuse to conform to the king’s new tyranny. What must More have thought and felt when visited by Margaret, his beloved daughter, who was pregnant with his grandchild? How could his paternal heart not break as he looked upon her? “He may be called almost the patron saint of family life,” Christopher Hollis wrote. “Of his [family] life there we have so many and such vivid pictures, and his happiness came to him so largely from it. His happiness was thus a happiness that does not differ in kind from that that is offered to every normal man and woman, and it is this very fact which heightens the horror and the grandeur of his final end. He stepped out to that end from just such a life as our own.”[4]

In comparing More’s imprisonment and passion with that of John Fisher, we see the palpable difference between the laity and the priesthood. More has a loving wife and children for whom he is responsible and who are his dependents. Fisher, on the other hand, has taken a vow of celibacy; acting in persona Christi, he chose the Bride of Christ (the Church) as His spouse. More has, therefore, more of an excuse for having divided loyalties. We can understand the temptation to equivocate with his conscience in order to succor his family. He is, therefore, to be praised and venerated all the more for having resisted it. A priest, however, is not in this awkward position. He has the Church as his Bride and is called to lay down his life for her. This absence of divided loyalties is one of the strongest arguments for priestly celibacy. It is, therefore, tragic, and an indictment of the weakness and cowardice of the Church’s hierarchy, that John Fisher was the only English bishop to defy the king. He serves, therefore, in his day and ours, as a potent symbol of the self-sacrificial duty of the bishops of the Church in all ages to resist the spirit of the world, the spirit of the age, and to remain true to the Body of Christ, serving the Heilige Geist and not the zeitgeist.

Bishop John Fisher, aging and ailing, was so weak on the morning of the execution that he had to be carried from his cell. As to the execution itself, we have an eyewitness account of his final words, spoken from the scaffold. “Christian people,” Fisher declared to the crowd gathered on Tower Hill, “I am come hither to die for the faith of Christ’s Catholic Church.”[5]

Although Fisher’s last moments epitomized the dignified courage which had characterized his life, there was nothing dignified in the manner that his body was treated following his death. Presumably on Henry’s orders, the decapitated corpse was stripped naked and left on the scaffold for the rest of the day. In the evening, it was removed unceremoniously to a nearby churchyard, where it was dumped, still naked, into a rough grave. There was no funeral prayer. Fisher’s head was stuck upon a pole on London Bridge where it remained for two weeks, its ruddy and apparently incorrupt appearance exciting much attention.

It was now Thomas More’s turn to face the executioner’s axe.

Three days after the martyrdom of John Fisher, Henry ordered preachers to denounce the treasons of Sir Thomas More from their pulpits. Since More’s trial for treason wasn’t due to start until a week later, on July 1, the king’s orders signified, if such signification were necessary, that the trial was already a foregone conclusion and that only one verdict would be tolerated. The parallels with the justice system in other secularist tyrannies, such as the show trials in the Soviet Union under Josef Stalin, are clear enough.

Mounting the scaffold on July 6, 1535, More turned to Edmund Walsingham to request his help ascending the steps to his place of execution. “I pray you, Mr. Lieutenant,” he quipped, retaining his sense of humour to the last, “see me safe up and for my coming down, I can shift for myself”.[6] From the scaffold itself, moments before his head was severed from his shoulders, he proclaimed to the gathered crowd of Londoners that he died “the king’s good servant, but God’s first”.

More’s head was taken to London Bridge where the severed head of John Fisher was still on gory display. Fisher’s head was removed from its place and thrown into the Thames. More’s head was then put in its place.

Hollis described More and Fisher as “the two most learned men in England” and their deaths as the killing of learning, as well as the killing of justice, laughter and holiness.[7] With such a sweeping judgment we can only partly agree. Whether More and Fisher were indeed peerless in learning is perhaps a moot point but their deaths did not kill learning, which continued “of a sort” (to quote Belloc),[8] nor laughter which would re-emerge uproariously in the comedies of Shakespeare, nor holiness, which always defies the grave, the blood of the martyrs being the seed of the Church. It did, however, kill justice or at least seriously weaken it. The king’s usurpation of the religious rights of the Church, and therefore the religious liberties of his subjects, set in motion a process of secular nationalism that would lead to the rise of the sort of secularism which ripens into secular fundamentalism. When the State gets too big for its boots, trampling on religious liberty, it is not long before the boots become jackboots, trampling on the defenseless and the weak, and piling up the bodies of its countless victims.

The final word on the legacy of John Fisher and Thomas More, and the final judgment (under God) on why we should see them as heroes, is given by G. K. Chesterton, a man who proves in his very self that the killing of More and Fisher did not kill learning, laughter or holiness. In an essay on Thomas More, Chesterton goes to the heart of what separates the pride of a king from the humility of a saint:

Henry always wanted to be judge in his own cause; against his wives; against his friends; against the Head of his Church. But the link which really connects More with that Roman supremacy for which he died is this fact: that he would always have been large-minded enough to want a judge who was not merely himself.… [T]here is this true relation between the martyr and the doctrine for which he died; that he died, not only defending the Pope, but defying the sort of man who wants to be Pope.[9]

This essay is an edited excerpt from Joseph Pearce’s new book, Faith of Our Fathers: A History of True England (Ignatius Press).

This essay was first published here in June 2022.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1] Richard Rex, “The Execution of the Holy Maid of Kent”, Historical Research 64 [1991], 220

[2] Technically they were guilty of misprision of treason, which, at the time, was itself considered to be treason and therefore a capital offence.

[3] Philip Caraman, ed., Saints and Ourselves (London: The Catholic Book Club, 1953), 76-7

[4] Christopher Hollis, St. Thomas More (London: Burns & Oates, 1961), 31

[5] Maisie Ward, ed., The English Way: Studies in English Sanctity from Bede to Newman (Tacoma, Washington, Cluny Media Edition, 2016), 212

[6] From William Roper’s Life of Sir Thomas More (1626); quoted in Hollis, 237.

[7] Hollis, p. 239

[8] Hilaire Belloc, “Lines to a Don”.

[9] Ward, ed., The English Way, 221

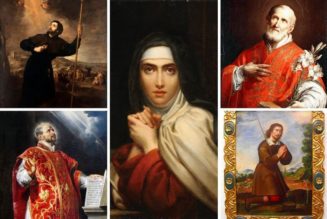

The featured image is a portrait of Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher (1600s), and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.