Hey everybody,

Blessed Solemnity!

Today the Church celebrates the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which, for most readers of The Pillar is a day of precept — so get to Mass, if you’ve not been already!

The Assumption is the sort of solemnity with great customs of processions and festivals to honor the Blessed Virgin Mary.

In New Jersey, where I’m from, a growing number of parishes are taking up again a longstanding Assumption custom that had, for some, fallen by the wayside.

They’ll have processions to the beach after Mass, carrying aloft a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary. In some communities, a priest will be rowed out past the waves, where he’ll bless the water of the sea — and in some cases, throw a wreath of flowers into the ocean.

The custom dates back at least as far as the 15th century, by some accounts, when a bishop reportedly threw his episcopal ring into the sea on the Assumption, to calm a growing storm.

Whether that’s true or not, the custom of a blessing for the sea is a good and beautiful one, and a helpful reminder that while the waves rage, the Lord is stronger than the storm — and that the Blessed Virgin Mary intercedes for us at the turbulent moments of our lives.

Plus, the other cool part of this custom is that it means the whole parish will be hanging out at the beach together after Mass and the ocean’s blessing, and hopefully prolonging summer just a little bit longer.

If you went to the beach this morning for a blessing, praise God. If not, maybe consider at least hanging around the parish parking lot to say hello after Mass, or inviting some friends over to toast the Blessed Virgin Mary with some beers or summer cocktails.

Her soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord. Her spirit rejoices in God the Savior.

On the feast in which she was assumed into heaven, let’s do the same.

The news

Astute readers of The Pillar likely recall that in November 2022, Cardinal Luis Tagle and the entire board of Caritas Internationalis were dismissed from their posts, as the centerpiece of a major Vatican-ordered shakeup of the global network of Catholic relief and aid agencies.

When the Holy See said the pope had made that move because of management “deficiencies,” the narrative emerged that Tagle himself had been an ineffective or incompetent leader at the agency — a surprise for those who had seen him as a competent Vatican figure with a longstanding ecclesial record.

Few details have emerged since the shake-up.

But Michel Roy, who was Caritas Internationalis’ general secretary until 2019, spoke with The Pillar this week, outlining his sense of what unfolded.

As Roy sees it, the Vatican’s Dicastery for Integral Human Development went too far, using complaints about management to absorb much of the agency’s management prerogatives.

From Roy’s view, that decision was beyond the pale: “At a time when clericalism is pinpointed as an evil, and when synodality is promoted as the best way forward for the Church, this decision is totally incomprehensible,” he told The Pillar.

“I see here a major issue of deontology: You direct an investigation — clearly, an unequal one whose result was already written before — and then you take the lead of the organization of which you have had the leadership ousted,” he added.

“That was also an opportunity to slap Cardinal Tagle,” Roy said of the Vatican’s intervention, alleging that Tagle was not removed for bad management, but as — effectively — a power grab by the Dicastery for Integral Human Development, which is led by Cardinal Michael Czerny.

Roy’s charges are extraordinary — and he doesn’t pull any punches — but he says they’re rooted in his experience in Caritas International’s top management position. They’ll no doubt prompt reactions from Vatican figures who support the dicastery’s decision.

—

In the wake of World Youth Day, you might have seen a fair amount of controversy among some Catholics, about liturgical decisions made at the Lisbon event, which concluded in a Mass with Pope Francis for some 1.5 million people outside the city.

The criticisms had to do with reverence and piety toward the Eucharist — concern with how Holy Communion was stored ahead of that vigil Mass, and concern with how it was distributed at another Mass.

In some corners, those concerns have been dismissed as the contrarian fussiness of the terminally online. I don’t think that’s fair: The Church can’t say, on the one hand, that she wants a Eucharistic Revival, and then blanch, on the other hand, by Catholics who hope to see the Eucharist revered — and who get concerned by the prospect of Eucharistic impiety at a major Catholic event.

If we want to help people revere the Eucharist, we should treat the Eucharist with reverence.

In any case, it’s our firm belief at The Pillar that facts should precede analysis — so in the case of the questions about World Youth Day, we went out and got the facts.

Was the Eucharist really reserved like this at World Youth Day?

Were these really the ciboria?

There are lessons on this front to be learned from World Youth Day Lisbon, and some of you are keen to discuss them. Have at it. I think that discussion is important, and I hope it will be had among bishops and liturgical planners ahead of other large ecclesial events.

Coleridge drew a line between what he called the “highly likely” prospect of married male priests for indigenous communities and women’s diaconal ordination, which he termed “a glimmer of possibility.”

The archbishop added that there’s “no way you’re going to recruit a celibate clergy in [indigenous] cultures,” which will require married priests for the Church to be effective in their communities.

The remarks are reminiscent of some perspectives offered during the 2019 Synod of Bishops on the Amazon region, during which Pope Francis was called to consider the priestly ordination of married men in some communities. The pope reaffirmed the “gift” of clerical celibacy in the Latin Catholic Church after that meeting.

The Pillar notes the resignation of Bishop Harrie Smeets of the Netherlands, who stepped down last week at 62 as he suffers the effects of a brain tumor.

Obviously, it would be a work of mercy to offer a prayer for Bishop Smeets.

But, in addition to his health problems, the bishop’s resignation is of note because of what preceded it — in July, Bishop Smeets attempted to declare his diocesan see impeded, declaring an unusual canonical circumstances, which the Vatican did not accept.

So what’s an impeded see? Why did Bishop Smeets declare one? Why didn’t the Vatican accept it?

All that sounds like good fodder for a Pillar explainer — and you can read one on the subject right here.

So what is an impeded see, anyway?

—

Finally, Wyoming Catholic College — a 200-student school in small town Wyoming — announced a new president last week: Kyle Washut, who served as academic dean of the college until his appointment.

Wyoming Catholic College is a small place, but it’s fascinating. It aims to combine a primary texts liberal arts curriculum with a lot of time outdoors — students go on mandatory backpacking trips and spend a semester working on their horsemanship. The school says its curriculum is based upon the notion of wonder — that experience of the world, and delight in creation, gives rise to a search for answers to the deepest questions.

Of course, with all that said, there are a lot of people in America who know something about Wyoming Catholic College because it’s the fictionalized setting for “Heroes of the Fourth Turning,” a finalist for the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in drama.

I talked this week with the college’s new president, about pedagogy, serving the Church, and about the fictional version of his institution. It was a wide-ranging and fascinating conversation.

Here’s an excerpt:

You know, when Catherine Doherty talks about the hermit tradition — the desert tradition — she makes a comment about the hermitage, which she calls the poustinia. She says the hermitage really only has three walls — that the fourth wall is open, so that the poustinia is integrated into the world around it.

And it seems to me that at Wyoming Catholic College, we’re inviting people out into the wilderness in some senses. We’re inviting them out for this kind of immersive encounter with reality.

But our encounter is not a kind of cloistered encounter. It’s an encounter that opens up onto the community that we find ourselves in.

…

We have a technology policy by which we ask the students to give up their cell phones. They check them in, they don’t have them while they’re here. We don’t have wireless internet in the dormitories. There’s a kind of a break —- even if you’re from a devoutly Catholic family.

Perhaps you’ve been tuned in, you’ve been locked into internet debates about Catholicism or internet apologetics, or you’re constantly concerned about what’s happening all over the world. And because of that, you’re not thinking about the reality right in front of you — there’s a way in which it becomes sort of an abstraction.

And so even for devout Catholics, to be able to come and make it real and intense, and have a kind of lay novitiate in a kind of radical way, is important.

—

I should be able to have a mai tai and enjoy a movie

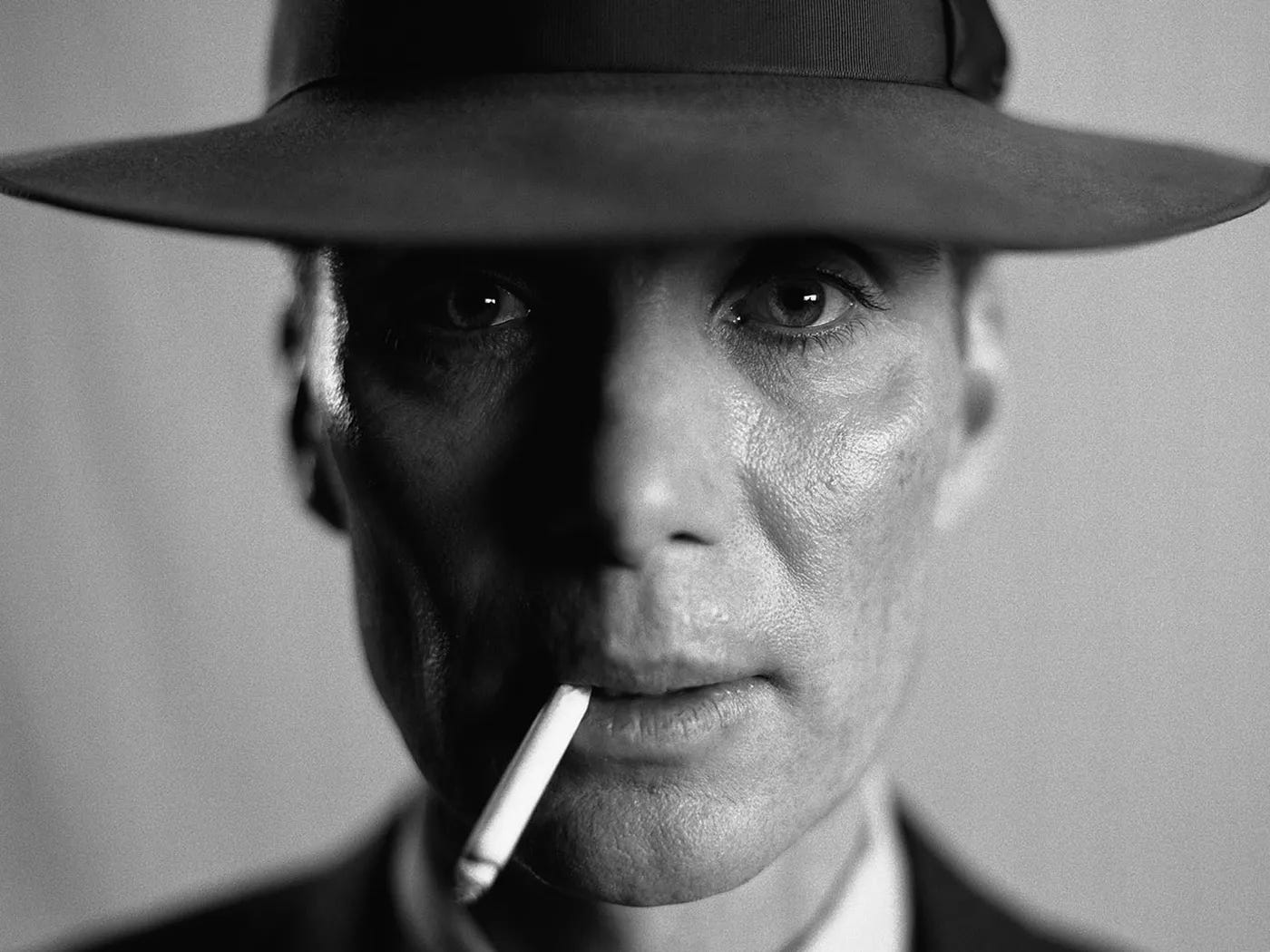

I saw last night “Oppenheimer,” Christopher Nolan’s bio-thriller on the life of American physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, who led the Manhattan Project during World War II.

I had planned to save my review of the film until I could debate it with Ed during this week’s episode of The Pillar Podcast, which we’ll do, for sure.

But I’d hate for anyone to spend their money on “Oppenheimer” without the benefit of a good forewarning.

I’ll offer three caveats:

— I saw “Oppenheimer” with my dad, who bought my movie ticket and my popcorn. I love going to the movies with my dad — a Pillar reader in a good way — so I should clarify to him that I’m reviewing the movie, not the experience. I’ll see a movie with you anytime, Dad. Especially when you buy the popcorn.

— I saw “Oppenheimer” after two Mai Tais, which packed more punch than I expected. Those Mai Tais didn’t impact my judgment, but they might have lowered my sense of decorum, which is why I laughed at some of the movie’s super serious parts.

— There was gratuitous nudity and sex in the movie. It didn’t need to be there, or — if, for some reason, it did — it didn’t need to be quite so graphic. It was to my way of thinking so ugly and mechanical that while sexual, it was not pornographic. It was salacious, but not titillating — an ugly exploitation of sex, in which the plot’s most bleak moral outlook was laid bare.

I wouldn’t take a young person to the movie, because of the sex, but for about 50 other reasons, too.

—

So, caveats aside, here’s my take:

“Oppenheimer” is a well-shot, well-planned, well-acted film, full of haunting cinematography, especially its focus on the face of its protagonist, which was used to tell masterfully a great deal of the story.

It captured well the bleak beauty of the desert, man’s quixotic quest to control nature, the folly of bureaucratizing the most powerful weapon in human history, and the moral depravity which gripped nearly everyone who got involved.

It was a film about Eden, and about Babel.

And it was a movie about actions with consequences, which might be entirely foreseen, and still vainly charged into.

The mode of storytelling was itself part of the story, it flashed between periods of time — it offered snippets, not sequences, to vivify that some calculation on a blackboard could set the world on fire.

In all of those senses, it was an interesting and powerful movie.

But it suffered the problem that most Christopher Nolan movies suffer from — it prized vibe over substance, nearly collapsing under the weight of its own “artfulness,” and its inconsideration to the viewer.

Christopher Nolan is the sort of filmmaker who is probably offended by the idea that he might do anything, ever, to accommodate people who plunked down 12 hard-earned bucks to see his movie, maybe after a pair of Mai Tais on an empty stomach.

If he isn’t going to tell his story sequentially, in the time-honored manner of storytelling, he might at least put the date in the corner from time-to-time, so that people watching the movie might have some idea what the hell is actually going on. Or make the flashback black-and-white, and put the present in color. Or have a radio announcer in the background say the year.

Christopher Nolan is rude, if you ask me, and borders on scornful toward the people who see his films. It’s cinema as ego trip. An audience is a privilege, not an irritation.

It’s one thing, I guess, for a movie like “Inception” to leave the viewer confused — and to confirm at the end that the whole thing was just one big mindjob, possibly devoid of actual rationality, but revered by the Nolan-gnostics as a work of genius, which normies like me are just too insipid to understand.

But “Oppenheimer” was ostensibly a movie about a real person who really lived through the real events depicted in the movie. Would it have been so hard to say “this part happened in 1959,” or “right now, it’s supposed to be 1946?”

Would it have offended Nolan’s artistic integrity to let people know what the real sequence of this man’s life actually was? Could he have maybe just put on the table, in some critical scenes, a newspaper with a date displayed?

I talked with someone this morning who read “American Prometheus,” the book upon which “Oppenheimer” is based. To them the movie was intelligible and coherent. Fair enough. But none of us should have to read the book to get the movie. That ‘s too much of an ask.

I’m not saying a weird, confusing movie is always bad — and I actually liked Nolan’s “Memento” very much.

But “Oppenheimer” is too clever by half — its effort to bend space and time — like a nuclear reactor, I guess — leaves normal members of the audience feeling like they got bombed by an insecure “genius” desperate to prove himself.

OH!

Maybe that’s the point.

Maybe “Oppenheimer” was more autobiography than biopic.

At least that’s what I’m going to say when fanboys tell me that my tastes are too middlebrow, and that I don’t deserve Nolan’s genius.

They’re right. I don’t deserve Christopher Nolan. None of us do, no matter our sins.

Or, maybe I am too middlebrow. Maybe I prefer a nice Tom Hanks-style biopic with a beginning, middle, and end. Maybe I just like, you know, normal movies.

I can live with that. For 12 bucks, just tell me a story that isn’t about how smart you are.

Einstein, by the way, was the most interesting character of “Oppenheimer.” Despite himself, maybe Christopher Nolan knows that he’s no Spielberg.

—

Anywho, have a blessed Assumption. Don’t forget to celebrate the gift of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Please be assured of our prayers. Please pray for us — we need it.

And if you can, please consider becoming a subscriber. The Pillar reports news worth paying for — and we need you on the team.

In Christ,

JD Flynn

Christopher Nolan nemesis

editor-in-chief

The Pillar

Comments 16

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews