Hey everybody,

Today is the Feast of St. Matthew, the apostle and evangelist, and this is The Tuesday Pillar Post.

In the news

Meet Juliana Taimoorazy

When Juliana Taimoorazy was smuggled out of Iran as a teenager, she probably didn’t expect to spend her adult life advocating for the religious freedom of women in neighboring Iraq. But — thanks to the invitation of Cardinal Francis George — that’s what she’s done. And now she’s nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

My classmates or the principals would tell me that I would burn in hell for my Christian name. My friends would corner me from time to time in the mornings and try to force me to convert to Islam by reciting the Shahada. And they would say ‘It’s not a big deal. It’s just one verse. Just say it, nothing’s going to happen to you.’

The religious teacher would try to debate me on the Holy Trinity. I was not a theologian, but as a 13-year-old, I would try to defend my faith, and I would be thrown out of class a lot. So, I have been a defender of Eastern Christianity for as long as I’ve known myself.

—

Going to the candidates’ debate

There’s not actually a debate, but there are candidates. The Pillar confirmed this week that two priests will be on the ballot in November to replace Msgr. Jeffrey Burrill, who in July resigned as general secretary of the USCCB.

The priests are Msgr. Michael Fuller and Fr. Dan Hanley, both of whom now work as officials at the conference. Fuller, who was on the 2020 ballot when Burrill was elected, has been conference interim general secretary since July. Hanley is associate director in the USCCB’s office of clergy, consecrated life, and vocations.

—

Francis critics and the synod on synodality

Ed analyzed last week the meeting of a Catholic group critical of Pope Francis — their spokesperson maligned the pope as “ultra-conservative” — who hope to influence the diocesan phase of the synod on synodality, which starts next month.

He noted the group said it hopes to use the synod process to call for changes to the Church’s doctrine on several issues.

Read about the “ultra-conservative” Pope Francis, and his critics, right here.

‘The integrity of the sacraments’

Pope Francis talked last week with reporters about abortion, politicians, and the Holy Eucharist. The pope said that, as far as he knew, he had never been approached for the Eucharist by Catholic politicians promoting legal access to abortion. Truth be told, a lot of priests probably fall into that situation — even while the issue has been fiercely debated by U.S. bishops, it doesn’t come up every day.

But in the Diocese of Springfield, Illinois, the issue has come up a few times. And at The Pillar, we found ourselves wondering how it actually happens that a priest or bishop decides to take the serious step of prohibiting someone from the Eucharist.

And if he does decide to do it, what happens next?

We talked with Bishops Kevin Vann and Thomas Paprocki about their experiences.

Here’s part of what Paprocki told us:

“I gave them the warning, which said that if you continue to promote these bills and they’re passed, then I will have to publicly say that you can’t go to Holy Communion in this diocese. And so they were well-warned and cautioned ahead of time.”

“When I issued the decrees, I said that their point is to call people to conversion. And that they would be an opportunity for a change of heart,” the bishop said.

…

“In my own conscience, I feel that if I did not properly enforce canon 915, I would be at least negligent, if not complicit, with those Catholic politicians who are promoting abortion,” he added.

On the upcoming debate between U.S. bishops, Paprocki was pretty direct:

“There was concern that making some statement would go against the unity of the bishops’ conference,” Paprocki said.

“If there’s a lack of unity, it’s unfortunate, if there are bishops who do not believe or do not want to enforce the Church’s teaching with regard to the worthy reception of Holy Communion.”

Wherever you land on the issue of canon 915, these voices are central to the discussion, and worth understanding.

Oh, Canada!

About 700 of you emailed, texted, or DMed me this weekend with an announcement from the Canadian Archdiocese of Moncton, which is now requiring that Catholics over 12 be doubly vaccinated to attend Mass.

Monitors are required by the archdiocese to record the name and vaccination status of all those in attendance.

We were all set to write about this, when, on Monday morning, the Vatican City State issued a new set of its own policies, which requires vaccines (or a negative test) to enter most of the city-state — except for attendance at Mass and other liturgies.

What most of you have asked is whether the Moncton policy — which, again, requires double vaccination for Mass attendance — is canonically permitted.

I’ve been giving that some thought.

First, it’s worth noting the context for the archdiocesan decision. The civic authorities of New Brunswick have said they’re on the cusp of returning to mandated restrictions on public gatherings and public spaces — but that if they can ensure that 90% of attendees in particular spaces are vaccinated, they believe they won’t have to do that.

Now, whether or not the government’s position seems reasonable to you, it is still the context in which New Brunswick dioceses have had to make decisions.

It seems the Archbishop of Moncton perceived he had a binary choice: eventually face attendance restrictions at Mass, or limit Mass attendance to the vaccinated. That’s a bad situation. He probably had other options — he could have filed a lawsuit against the provincial government, or simply directed his churches to disobey any eventual restriction. But those aren’t ideal choices either.

So agree or not with the choice he made — and nearly every Catholic I’ve spoken with has raised some objection to it — the context helps to account for how the archbishop might have arrived at his decision.

With all that said, is the policy canonically legal? And, more to the point, is it just? Let’s take a look:

I reached out yesterday to the Moncton archdiocese to ask whether vaccines were also required for Catholics wanting to attend confession, and whether their names are required to be collected as well. The archdiocese has not gotten back to me. But I think it would be clearly canonically problematic if Catholics were required to submit their names, or provide identification, in order to avail themselves of a sacrament which is supposed to be anonymous, and protected by an “inviolable seal.”

In fact, that kind of thing has happened during the pandemic, and in some places may still be happening. But most pastors have been sensitive enough to realize that since disclosing who goes to confession can actually be a canonical crime, they shouldn’t be recording names outside the box.

Priests in a lot of places have been terrifically creative during the pandemic in order to ensure that the sacrament of penance remains available.

But what about Mass? Can Mass attendance licitly be restricted to those who are vaccinated?

The Mass is the work of the entire Church. Canon law says that Masses “are to be celebrated with the presence and active participation of the Christian faithful where possible.” But it is not the case that every Mass offered in the world must be open to the public.

Priests offer Mass privately on their days off, religious communities celebrate Mass singularly for the community, and some high-interest events are ticketed, owing only to the limits of space. While it would be a sin to sell tickets to a Mass, or even make them available with the suggestion of a donation, it is not innately immoral or canonically illicit to require tickets or an invitation for entry to some Mass.

But in an ordinary parish church, for an ordinary Sunday Mass, some other issues come into play. The first is that a parish church is “a sacred building designated for divine worship to which the faithful have the right of entry for the exercise, especially the public exercise, of divine worship,” according to the Church’s canon law.

Restricting the right of entry to that space during public exercises of divine worship — in other words, regularly scheduled parish Masses — requires some just and reasonable cause. It is not to be something done lightly. And a restriction which might prevent someone from attending Mass on Sunday is all the more grave.

In the Church’s life, Catholics really are sometimes prohibited from attending Masses, for causes believed to be just and reasonable. A person who is habitually and maliciously disruptive, for example, might be prohibited from attending Masses at a certain parish. And some dioceses restrict the rights of registered sex offenders — permitting them to attend only certain parish Masses, for example, and not “school Masses” or similar events.

The point of norms like that is to ensure that the community’s duty to worship is not impeded by some clear and significant danger.

But when an entire class of persons — the unvaccinated — will be restricted from attending Mass, a clearly compelling and just cause seems all the more obviously necessary. Especially because the CDF has insisted that while vaccination is an act of charity oriented toward the common good, it has also said that people have the right to decide whether or not to receive it, with correspondent responsibility to take reasonable precautions against spreading the virus.

In short, there is no hard and fast canonical norm — no positively promulgated piece of canonical legislation — which says definitively that prohibiting unvaccinated people from going to Mass is canonically illegal. The legislation of Vatican City — which requires vaccination for attendance at all kinds of events, but not for attendance at Mass — would seem to indicate the Church’s preference on the matter.

But as to the policy in the Moncton archdiocese — which effectively prohibits a class of persons from attending Mass — the only way to know whether it is canonically prohibited is for some Catholics to make a recourse, or appeal, to Rome.

I suspect that will probably happen.

The canon lawyers consulted by The Pillar predicted that an appeal to Rome would end with Vatican insistence that the archdiocese make some accommodation for unvaccinated people to attend Mass — either offering Masses outdoors, or in some central locations for them. Several said they believe the Church will decide the archbishop has an obligation in justice to accommodate them.

While Catholics unable to attend Sunday Mass are not bound to the impossible, impeding one class of Catholics from going to Mass on Sunday, while permitting others to do so, is not expected to sit well at the Congregation for Divine Worship.

In the meantime there is a related issue worth noting. Canon law is clear that “any baptized person not prohibited by law can and must be admitted to holy communion.”

The law adds that while the Eucharist should usually be received at Mass, “it is to be administered outside the Mass, however, to those who request it for a just cause, with the liturgical rites being observed.”

It seems clear that being prohibited from attending publicly scheduled Masses is a just cause to request the administration of the Eucharist in another context.

Therefore, whatever is finally decided about Mass in the Moncton archdiocese, Catholics who are not now able to attend Mass — namely those who are unvaccinated — have a strong case to call for the provision of the Eucharist to them in some other setting — perhaps on the church steps, or some other well-ventilated area, after the Massgoers have left the church?

—

All of this raises a point I’ve made before, and think is worth continuing to make. I continue to talk with pastors, principals, parochial vicars, parish staffers and diocesan officials who find themselves hammered on all sides by Church decisions about the pandemic — considered draconian and unbending by some Catholics, and woefully irresponsible by others.

In many cases, the decisions being made aren’t really theirs anyway — but they bear the brunt of the angry phone calls at work, and in some cases, the cold shoulders in their personal life.

That isn’t fair. But for some people working in the Church, it’s not especially unusual.

“It’s hard to work in church,” one diocesan official said to me last week. And indeed it is. A lot of things in life are hard, and this is not meant to single out only one group — call them professional Catholics — for sympathy. But I raise them here because many of our readers work in and around the Church’s institutions, and many of them are continuing to feel acutely a kind of spiritual exhaustion from the challenges of the past 18 months.

Imagine, for example, what it might feel like to be one of Moncton’s few diocesan priests, and, agree or disagree with it, be charged with implementing the archbishop’s decision.

Appeals of that decision — and decisions like it — are well within the rights of Catholics, and sometimes an effective and important way to safeguard rights, clarify ecclesial questions, and ensure justice. And for the Catholics I’ve spoken with, appeals are not the issue that have gotten them down. The issue is tension, a presumption of bad faith, the challenge of implementing unpopular decisions made by someone else, and an enduring situation of unpredictability.

Well, dear readers, know you’re not alone. Know that other Catholics in ecclesial ministry are experiencing what you are. And know that many more, including many who read this newsletter, are praying for you. Some are offering Mass for you. And some are praying even while they file appeals!

Let’s all continue to pray for another. Lord knows, we need it.

St. Matthew’s genealogy

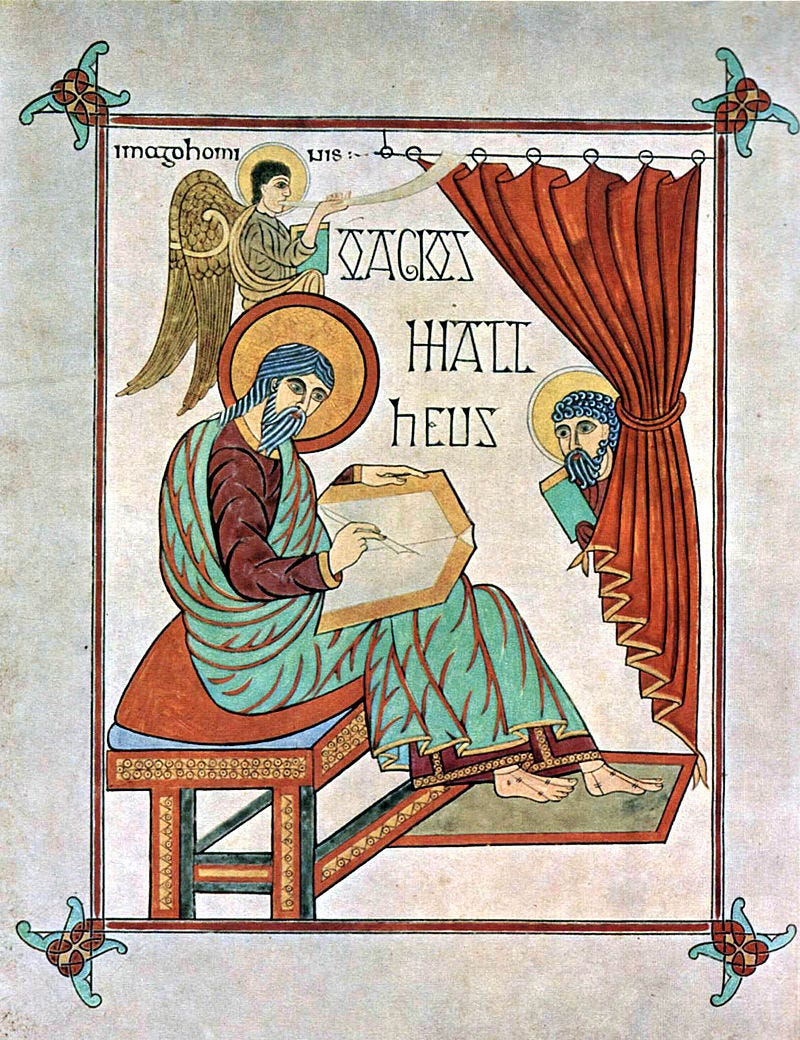

You probably know that each of the four evangelists, the writers of the Gospels, are depicted with the symbols of living creatures.

St. Matthew, whom we celebrate today, is traditionally depicted as a winged man. Mark is shown as a lion, Luke as an ox, and St. John as an eagle.

The symbols come from a vision of the prophet Ezekiel, and were first associated with the four evangelists by St. Irenaeus, a father of the Church.

But it was St. Jerome who popularized that association. Jerome associated Matthew with the symbol of a man, rather than one of the other figures, because Matthew began his Gospel with the genealogy of Jesus. That genealogy, by the way, is important.

In his work interpreting the Scriptures, Cardinal Ratzinger says that Matthew’s account of Christ’s genealogy is really an account of God’s enduring promise to Abraham: That “all the nations of the earth shall bless themselves by him.”

From the beginning of the genealogy, then, the focus is already on the end of the Gospel, when the risen Lord says to the disciples: ‘Make disciples of all nations’ (Mt 28:19). In the particular history revealed by the genealogy, this movement toward the whole is present from the beginning: the universality of Jesus’ mission is already contained within his origin.

Reflecting more on the details of the genealogy, Ratzinger eventually comes to Mary:

Most important of all is the fact that the genealogy ends with a woman: Mary, who truly marks a new beginning and relativizes the entire genealogy. Throughout the generations, we find the formula: ‘Abraham was the father of Isaac . . .’ But at the end, there is something quite different. In Jesus’ case there is no reference to fatherhood, instead we read: ‘Jacob [was] the father of Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born, who is called Christ’ (Mt 1:16). In the account of Jesus’ birth that follows immediately afterward, Matthew tells us that Joseph was not Jesus’ father and that he wanted to dismiss Mary on account of her supposed adultery. But this is what is said to him: ‘That which is conceived in Mary is of the Holy Spirit’ (Mt 1:20). So the final sentence turns the whole genealogy around. Mary is a new beginning. Her child does not originate from any man, but is a new creation, conceived through the Holy Spirit.

The genealogy is still important: Joseph is the legal father of Jesus. Through him, Jesus belongs by law, ‘legally,’ to the house of David. And yet he comes from elsewhere, ‘from above’-from God himself. The mystery of his provenance, his dual origin, confronts us quite concretely: his origin can be named and yet it is a mystery. Only God is truly his ‘father.’ The human genealogy has a certain significance in terms of world history. And yet in the end it is Mary, the lowly virgin from Nazareth, in whom a new beginning takes place, in whom human existence starts afresh.

Jesus Christ is a new creation, conceived through the Holy Spirit, and he is the true Son of the Father. And through him comes a message of salvation for every nation, and culture, and people. And for every one of us.

That’s the promise of St. Matthew’s Gospel. And it’s manifested in the life of St. Matthew himself. A tax collector — an imperial stooge, perhaps a cheat — was called by the Lord, and became in Christ a new creation. He came into the promise of the Lord’s incarnation. And whatever our own sins, we too are called, and we too can come into the promise.

That’s what we celebrate on today’s feast.

St. Matthew – tax collector, evangelist, and new creation in Christ – pray for us.

Finally…

The flood of Haitian migrants and asylum seekers is both a political and human crisis that is compounding an already broken asylum and immigration system, and compounding human crisis at our southern border. It goes without saying that many of the Haitians amassed at the border are fellow Catholics — our brothers and sisters in Christ — and it goes without saying that the federal government seems committed to bipartisan sclerosis on the issue.

If nothing else, each of us can and should pray for the Haitians, and others, at the border, and for a just, humane, and charitable solution to a complex and long-building problem.

And if you want to read about the Church’s work with migrants at the border, and the challenges we’re facing, this op-ed, from Bishop Daniel Flores, is a good place to start.

—

Congratulations to Jessica Rowell and Fr. [We-don’t-know-his-first-name] Manning, who won our contest last week. We’ll be sending them Pillar t-shirts. And if you share this Tuesday Pillar Post, and let us know in the comments, we’ll pick another winner this week. Thanks for passing The Pillar on — we appreciate it.

—

Mrs. Condon is due anytime now with the Condons’ first child.

If, like me, you enjoy reading Ed’s work each week, and, like me, you forgot to get his family some kind of baby gift, I have got you covered.

For less than the price of a onesie, an expensive French giraffe baby-toy, or a trendy Mozart MagicCube from Amazon, you can just get Ed’s baby a subscription to The Pillar.

It’s a little known fact, but Ed’s baby, and babies in general, love supporting the kind of smart Catholic journalism that makes a difference in the Church’s life. And the cool thing is that if you get Ed’s baby a subscription to The Pillar, it will come to your inbox, and the baby won’t mind if you read it too. Ed’s baby is rather generous that way.

—

In last week’s Pillar Podcast, we talked a lot about the life and ministry of the Church, and also a fair amount about platypodes. I forgot to mention that platypodes are biofluorescent; their fur glows under a black light. But listen here to the episode anyway.

And in case you want to learn more about the platypus, here’s a somewhat strange video of a guy taking one out of a box, posing with it, and releasing it into the wild.

Blessed Feast of St. Matthew. Please pray for us, and be assured we’ll be praying for you.

Yours in Christ,

JD Flynn

editor-in-chief

The Pillar

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity