It has been a while since there was news from Boston of cravenness and cowardice on the part of its Catholic Archdiocese. The streak was broken this week. From the New Boston Post:

The Catholic chaplain has been forced out at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology because of an email message he sent Catholic students that questioned whether George Floyd died because of racism and stated that Floyd did not live a virtuous life.

Father Daniel Moloney, a priest of the Archdiocese of Boston, was asked to resign last week, according to the archdiocese.

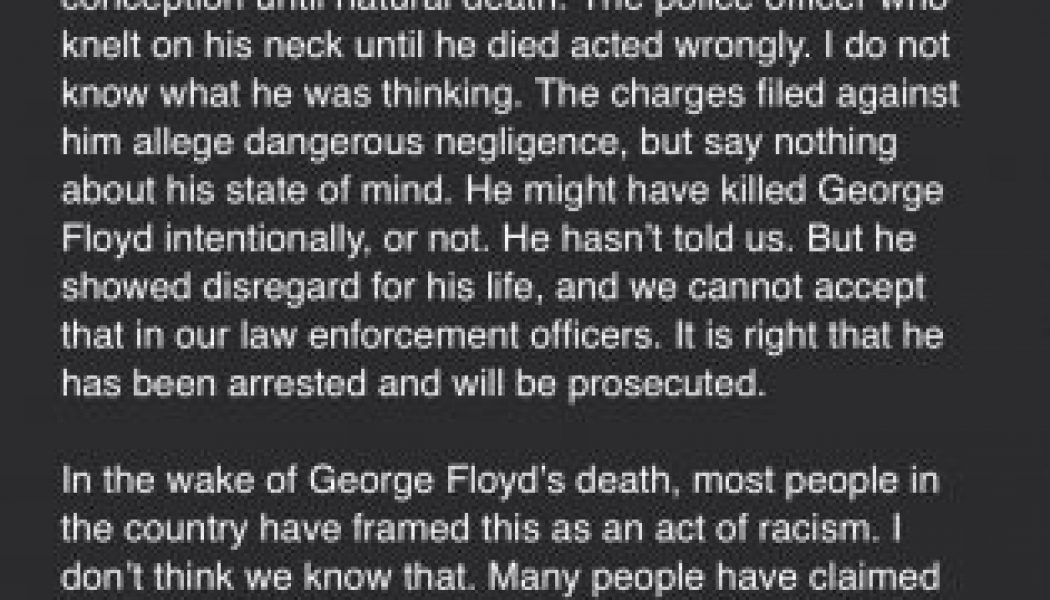

“In the wake of George Floyd’s death, most people in the country have framed this as an act of racism. I don’t think we know that. Many people have claimed that racism is a major problem in police forces. I don’t think we know that,” Moloney wrote in an email message to the MIT Catholic Community, according to a news story published Tuesday night in The Boston Globe.

Moloney, according to the Globe story of Tuesday, June 16, wrote that Floyd should not have been killed by a police officer in Minnesota, but also stated that Floyd “had not lived a virtuous life” and that police “deal with dangerous and bad people all the time, and that often hardens them.”

Some students complained to university administrators, including the university’s Bias Response Team.

University officials contacted the Archdiocese of Boston, which quickly sought Moloney’s resignation.

What did Father Moloney write? Someone posted the text of his e-mail on Twitter. Here are the screen shots; notice that there is a bit of overlap in the text of the messages, in the images:

What on earth is wrong with this e-mail? He is simply stating a fact: that George Floyd had not lived a virtuous life, but that he did not deserve to die like this. Perhaps Father Moloney was speaking to some things that had been going around the Internet — I saw them myself — in which people minimized the horror of Floyd’s death by saying that he was a criminal who was high when he was arrested. Here is a priest telling his flock that even a great sinner possesses human dignity, and should not be treated that way.

The priest also said, truthfully, that we don’t know that Officer Chauvin acted out of racism. It’s not clear yet what his state of mind is. The thing that we can know for sure, though, is that Chauvin’s act was evil. He also makes the perfectly true and reasonable point that police officers, who keep us safe, put themselves into situations that could brutalize their consciences. It doesn’t justify such behavior, he says, but it helps us understand how Chauvin’s killing of Floyd could have happened. We don’t know that yet, so we need to be careful about passing final judgment on either man.

This is how sin works, the priest says: it spreads like an infection through all things human. And he is right. This is the tragedy of being human: even those who seek to do good may find themselves suddenly doing evil, and even those who have done evil may find themselves victimized unjustly. The Catholic Church opposes the death penalty because nobody loses their dignity as children of God, no matter what they have done. This is what the priest is reminding his flock.

The priest goes on to say that we depend on solidarity in a time like this. He notes how divided his flock is over the Floyd killing, the protests, and the riots, and calls them all back to charity with each other, not rash judgment. He points out that people who would have admired each other for their shared opposition to racism and other evils now find themselves hating each other. Again, the tragedy of sin. He ends by calling on his flock to seek to be peacemakers.

That’s it. That’s what Father Daniel Moloney wrote. But hotheads were outraged. How dare he speak of this tragic, complex situation as if there were more to it than simple right and wrong! How dare he remind people that everyone involved in this act of killing — Floyd, Chauvin, cops, the people they police, protesters, rioters, and people angry at the protesters and rioters — are all fellow human beings, and that we need to bear with each other in love and solidarity, as brothers and sisters!

That was too much for these hotheads, including an MIT official:

Suzy Nelson, an MIT vice president and dean for student life, sent an email to students calling Moloney’s comments “deeply disturbing.”

“By devaluing and disparaging George Floyd’s character, Father Moloney’s message failed to acknowledge the dignity of each human being and the devastating impact of systemic racism,” Nelson wrote.

This is a flat-out lie! Father Moloney’s e-mail was entirely about the dignity of each human being: Floyd, Chauvin, protesters, and everyone else!

God forbid the Archdiocese of Boston show any spine, or the faintest brush of integrity. It forced Father Moloney out, denouncing his e-mail as “wrong.” Perhaps MIT gave the Archdiocese no choice in whether or not the priest could remain in his post there, but why did the Archdiocese throw the young priest under the bus by holding him out as a villain here?

Father Moloney said what his flock needed to hear — but not what they wanted to hear. And for that, he paid a price. A Catholic reader e-mailed me to say:

We’ve all lost our minds, and the Church is as craven as the rest of them. They tell the guy to resign over having said two utterly sane things: I don’t know how you know that George Floyd’s death was necessarily a racist act (an argument Loury and McWhorter and have making prominently), and that racists are sinners in need of mercy. If THE CHURCH purges such heterodoxy from its midst, then there really is no place to hide.

This wouldn’t be the first time that faithful Boston Catholics needed to find a way to experience solidarity against the moral cowardice of the institutional church, now would it? What a thing it is to suffer more from the Church than for the Church…

Prof. James Matthew Wilson, a Catholic who teaches literature at Villanova, suggested on Twitter this week that people pondering Father Moloney’s message should read Flannery O’Connor’s short story “Revelation.”Pay attention to the words: “…even their virtues were being burned away.”

UPDATE: This just came in. The priest asked me to blur certain identifying remarks, and I’ve agreed. There’s a particularly important point he made, but he’s afraid if I publish it, it will out him to people:

I’m a Catholic cleric in a very progressive part of the country. I am painfully aware that anything I say or do can and will be used against me, so I have been very aware of the buzzwords that would set the mob off and have avoided them like the plague.

Unfortunately, even with avoiding the bloodshot eyes of the mob, I still have received a couple of notes of grievance from people about not being sufficiently aligned. One person stated that anyone who disagreed with him was a racist and they couldn’t dialogue with them because the other side was filled with hate. My charitable read is that he thought I was thinking of the KKK or something… but my fear is that he meant a different group of people…people like you.

Another long long letter I received accused me of misogyny, arrogance, privilege, and countless micro-aggressions, if not outright racism. The classicly ‘woke’ line was ‘it’s not the intention of your words, it’s just your impact.” This was, ironically, right after they said that if they received a similar letter in their own profession they would be devastated. I wonder what their intended impact was… They were angry that I thought privileged white philosophers I’ve quoted could describe what’s going on today (which I believe is so much deeper than what most people would like to think) instead of… Ibrahim Kendi. Their suggestion, not mine.

I do wonder which one might provide a more comprehensive Catholic position: a daily mass-goer steeped in Scripture, or an activist “millennial, raised in a Christian home, with both parents embracing a James Cone-like Black liberation theology, who believes” that Christianity’s main gist is “struggle and liberation,”(https://christiancitizen.us/how-to-be-an-antiracist-a-prescription-for-healing-america-book-review/), who wants to establish what sounds like an Orwellian committee on anti-racism to police every action by every company (and religious organization) in the United States? I fear it’s already a fait accompli.I would be curious your perspective on Alasdair McIntyre’s thoughts, especially in After Virtue. I have seen a consistent erosion (or vacuum?) of a coherent social theory, even within the Church. I learned all about Catholic Social Teaching in Catholic School… but never had a class on Catholic virtue. I don’t think these are opposed to each other, but looking back on the Catholic Social Teaching Class, it was deeply moralistic: without any roots in the Incarnation or understanding of virtue — natural or supernatural! I know some of my parishioners recognize what’s going on: they’ve told me — but I also know if I sent what they have told me around they would be cast out of their university positions and public jobs.

Here is a quote from Strange Rites: New Religions For a Godless World, a fantastic new book published this week, written by Tara Isabella Burton. It’s a journalistic account of how religion is changing in post-Christian America, with particular focus on the rise of interest in DIY occultism:

Today’s Remixed religions valorize different forms of emotional experience — a person’s perceived “energy” as a clue to their bad character, a modern witch’s sense of divine presence during a spell casting session, a feminist’s “lived experience” as an authoritative account of living in the world — as the key to interpreting both their meaning and purpose. They value, too, authenticity: the idea that one’s actions are in harmony with one’s emotions. They’re less keen on rules, or doctrines, or moral codes they dismiss as restrictive or outmoded. They’re suspicious of moral or truth-claims that don’t root themselves in subjective experience. Three-quarters of Millennials (and 67 percent of the religious “nones” overall) now say they agree with the statement “Whatever is right for your life or works best for you is the only truth you can know,” compared with just 39 percent of the elderly. (And 47 percent of practicing Christians of all ages). They demand agency, creative ownership, in their spiritual lives, dissatisfied with the narrowness of options available. Among the most common saying I heard among the people I interviewed was “I make my own religion.”

(TIB gets those figures from this 2016 Barna study.)

MacIntyre saw it all coming in After Virtue (1981). For that matter, so did Philip Rieff in The Triumph of the Therapeutic (1966).

Here’s the second MacIntyre point I want to make, responding to my priest correspondent’s query. MacIntyre says that people learn moral reasoning through communities of practice. Catholics no longer have that — nor, I think, do many churches in contemporary America. That is, we are not living in communities where people share coherent ideas of right and wrong, and how to think morally. It’s emotivism almost all the way down. This is why I’ve promoted, via The Benedict Option, Christian communities coming together to raise their children within such small communities. It’s not failsafe, but it’s all we have.

UPDATE.2: A reader:

With respect, no, Candace wasn’t making a version of that argument. She states very clearly in her video that the killing was unjust and she hopes that Floyd’s family recieves justice. All she said is that she was uncomfortable with the way some people were elevating him into a saint, something some of your commenters are saying.

This is perceived bad only in the same way Father Moloney’s comments are being percieved as bad, because of tone-deafness and insensitivity.

Granted, Moloney’s message is far more nuanced than Candace’s were; and while she’s simply being contrarian to public sentiment, he leads towards a Christian message about finding brotherhood with each other and reading things people say with charity, rather than suspicion. But this same attitude of charity would apply to interpreting Candace’s remarks, wouldn’t they? The problem is many people who had a knee jerk reaction her video don’t care about nuance, so they don’t care about it in Moloney’s message, either.

If I have mischaracterized Candace Owens’s statement, I apologize and retract. I was going on the way it was repeated to me.

UPDATE.3: Here is a Father Moloney blog post from June 6 that goes in-depth into his thinking about the George Floyd killing, and mercy. Excerpts:

This week, we’ve been focused on how people of different races don’t love each other. Last fall, in the wake of the Jeffrey Epstein revelations and the #MeToo movement, we focused on how men don’t treat women with respect. Before that, we were concerned about how we treated immigrants. And so on. It seems that we get outraged by whatever part of fallen humanity the media causes us to focus on right now, until the next news cycle refocuses us on the sin over there. We can always find genuine, real, interpersonal animosity if we look for it, since we can always find the fallenness of humanity if we look for it.

We can hate people who are different from us. And, as the story of Cain and Abel teaches us, we can hate people who are a lot like us. A few years ago, we were focused on how Irish Christians, racially indistinguishable from each other, were killing each other. We were shocked about how Rwandan Catholics, all of whom are black, conducted a genocide against each other in the 1990s. This Wednesday, we celebrated the feast of Charles Lwanga and the Ugandan martyrs, all members of the Gandan people, who were killed by their own king for refusing his homosexual advances. Husbands and wives, who profess their lifelong love on the day of their weddings, come to hate each other in the wake of the divorce. Mothers kill their own children by the millions through abortion, from some misguided sense of self-preservation (a species of self-love). We can grow to hate or mistrust anyone who isn’t us. That’s the lesson of original sin.

Charity, the greatest gift of the Holy Spirit, is the love that overcomes our anger at injustice and the sinful divisions that follow. Without charity, without grace, our concerns shrink: from a love of all mankind, to a love of our tribe (literal or metaphorical), to a love only of those like us, to a love of this family member but not that one, to a love of ourselves above all, even above Christ. Charity is the love that tears down the walls that divide us. Charity is the readiness to give our lives for those we love, in imitation of Christ’s sacrifice.

As the sad examples of Northern Ireland and Rwanda make clear, Catholics are not free of the temptation to selfishness and even to murder. The Church has had and will always have sinners within it. And yet, in the Creed we say, “we believe in one holy… Church.” This is a dogma. It doesn’t mean that the Church includes only those who are without sin, but rather that the Church is holy insofar as we allow the Holy Trinity to work within us. Through the Holy Spirit, we are baptized into Christ Jesus and his covenant with the Father. When we genuinely act and pray in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, we are holy. Charity is a participation in the interior life of the Trinity.

In my book Mercy, I talk about how a great part of the difference between Christian thinking and secular thinking about politics comes down to mercy, to how we respond to injustices. The mistake of what I call “justice-only politics” is to have well-developed ideas about how things ought to be (aka justice), but no concept of mercy, no real thought about what to do when circumstances and/or people get in the way of their idea of justice.

I think the national reaction to the killing of George Floyd reveals something like this. Some people think that the right thing to do is to enact reforms of the police; others think that the right thing to do is to kill the police and bomb the precinct. Some people think that nonviolent protests are an appropriate response; others think that injustice justifies robbing the local Target. Some people are satisfied when the bad cops are arrested, prosecuted, and convicted; others want to overthrow the government. Some are just so upset that they don’t know what to do. All agree that something deeply wrong happened to George Floyd, but our consensus stops there, at the level of justice.

Mercy is the virtue that comes into play when things go wrong. Once we decide that something is unjust, we still have to decide what is the right thing to do. Do we “cancel” the unjust persons, breaking solidarity with them and removing them from society? Do we send them to the guillotine? Or do we try to make things better? In an interesting Trinitarian statement, Jesus commands his disciples to “be merciful as your heavenly Father is merciful” (Luke 6:36). So justice-only politics, or any politics without solidarity for the offender and the sinner, is not a Christian option.

More:

Racism is a sin, and Jesus conquers sin. It’s a sad fact that most of our thinking about race takes place in a left-wing, Marxist, atheistic context, in which a desire for power and an awareness of otherness crowd out Christian reflections on meekness and solidarity. It didn’t used to be this way. The Civil Rights movement was once led by Christians, most notably the Protestant Pastor Martin Luther King. It appealed to the Gospel to unify people of all races. As in so much of our life, so to with regard to race, it’s a struggle to think in Christian terms. When people only talk about justice, it’s a struggle to cultivate mercy. It’s a struggle to forgive those who have trespassed against us, or people like us. It’s easy to forget what we said above, that mercy is commanded of us.

For this reason, I highly recommend that we Catholics foster a desire for mercy, pray for mercy, and perform works of mercy as much as we can. June is the month devoted to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, a symbol of his suffering for us out of his merciful love—the Solemnity of the Sacred Heart is Friday, June 19, a time when many people consecrate themselves to the Sacred Heart. Many people find that the Chaplet to Divine Mercy helps realign their hearts with Jesus’, so that they can regard people with his merciful eyes and love them with his merciful heart. Both devotions call attention to Jesus’ Passion, the steep price that he paid to conquer sin and division. We’ll find that we, too, have to pay a steep price to conquer the sin in our own hearts—that we cannot be casual or lazy about our own spiritual lives if we want to help the world to be better.

There are no spiritual shortcuts. To conquer racism requires a conversion to holiness, and a willingness to spread grace and charity to hardened hearts. Only through baptism into Christ’s Ascension can any fallen human being participate in the inner charity of the Trinity. Let us ask the Holy Spirit to transform our lives.