There is an easy way to tell whether or not the Church is following the way of servant leadership and suffering that Jesus describes this Sunday, the 29th Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year B.

Where Christian leadership means serving and suffering, numbers are growing. Where Christian leadership means “lording it over” others, numbers are falling.

In the United States, our numbers are falling. Fast.

We who practice and love our Catholic faith make a critical error when we think that makes us the “betters” of other people.

In the Gospel for this Sunday, James and John approach Jesus and, like us, feel they have a special relationship with him. They have good reason to think so. He has a special nickname for them, “the sons of Thunder,” and he picked them out for all kinds of special favors — seeing Jairus’s daughter raised and witnessing the Transfiguration.

So they approach Jesus and ask something strange: “Teacher, we want you to do for us whatever we ask you.” He is God and they are not, but they speak to him like an earl would speak to a butler.

Jesus’s answer is, if possible, even more strange. He answers the way a butler would answer back. “What do you wish for me to do for you?” he says.

We treat Jesus exactly this way. Like them, we feel, with good reason, that we have a special relationship with Christ. We have gazed upon the Blessed Sacrament with belief and longing and sacrificed for him while most people ignore him or treat him with contempt. Since we have done this, when we pray, we also expect him to snap to attention and give us whatever we ask.

James and John deliver their request: “Grant that in your glory we may sit one at your right and the other at your left.”

What they picture in their minds is a trip to Jerusalem where Jesus will establish his throne over the Romans and pick his right- and left-hand men from among his apostles. What they don’t realize is that his throne will be a cross and that condemned criminals will be to his right and left. It is this sacrifice on the cross that Jesus is inviting them to when he says they their only path to glory is to “drink the cup that I drink” and be “baptized with the baptism with which I am baptized.”

This is the deeper meaning of the initiation we receive in baptism and Eucharist — for us as much as James and John.

We have heard what the sacraments mean: We are baptized into Christ’s death and resurrection and we partake in his body and blood, offered for us on the cross and at Mass. Catholics who are “in the know” understand that Jesus is truly present in his sacraments: We really become members of his body in Baptism and we truly receive him in the Eucharist. But we might think that at least the “dying” and “suffering” part of the sacraments are symbolic — that he did that part so that we don’t have to.

Maybe that’s what James and John had in mind when they said they were willing to drink his cup and be baptized with his baptism. “We can,” they said. “You will,” Jesus answered. And then they did. James was killed by the sword. John was exiled on an island.

But that was the early Church, right? For us, we think, baptism and the Eucharist will just be a matter of a respectable life, serious but comfortable. But many Christians in the world know the truth: baptism into Christ’s death often means you will die too, and communion with his blood will mean spilling your blood, too. The 20th century saw more martyrdoms than all the previous centuries combined; and the 21st century is on pace to set a grim new record.

For us in the West, as Christianity grows more and more countercultural, the sacraments will grow increasingly costly too.

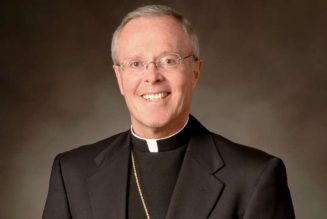

This “law of suffering” goes double for priests and bishops.

To get a sense of what the Gospel is talking about, imagine a child asking his parents if he can take over the farm. The child thinks this is simply a matter of being declared the boss. The child may think being in charge will be a way to escape certain chores. The parents know that being in charge of a farm entails a lifetime of early hours in the cold, late nights of worry, and every variety of pain. They know that on a farm the “boss” isn’t a pampered ruler, but a virtual slave not just to the needs of every family member, but to the needs of every cow, chicken, and pig.

“To sit at my right or at my left is not mine to give but is for those for whom it has been prepared,” said Jesus, which is another way of saying “I can’t give you this; you only get it through blood, sweat and tears.”

Today, as in many dark times of the Church’s history, priests and bishops in the West often act like princes and bosses rather than like servants. This is obvious in the sex abuse crisis but it shows up in the attitudes that persist among many pastors who live in relative luxury and consider the Church their fiefdom. When bishops and priests “lord it over” their flock and “make their authority over them felt,” scores of people choose “none” when asked what their religion is.

In the suffering Church, from Afghanistan to Iran to Africa, bishops and priests often live in poverty and lead in suffering, and the Church has grown by leaps and bounds.

In the Second Reading, from Hebrews, and the First Reading, from Isaiah, God shows us the ultimate example of priestly love.

“For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses,” Hebrews says, “but one who has similarly been tested in every way, yet without sin.”

Jesus himself was the high priest who was the very greatest VIP, the Second Person of the Trinity, who subjected himself to everything we suffer — and more. “He gives his life as an offering for sin,” says Isaiah, and “through his suffering my servant shall justify many, and their guilt he shall bear.”

Jesus tells bishops and priests (and the laity) to do the same: “Whoever wishes to be great among you will be your servant; whoever wishes to be first among you will be the slave of all. For the Son of Man did not come to be served but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many.”

Jesus’s “ransom” of us is a key concept.

Mark quotes Jesus saying he was a “ransom” for many; Paul tells Timothy Jesus was a “ransom” for all; the Ephesians find out that this “redemption” came through his blood.

We think of ransom as giving money to a kidnapper; for the Jewish people it meant freeing a slave through blood.

God called Israel his “firstborn son” and their freedom from Egyptian slavery cost the blood of Pharoah’s firstborn sons and a lamb in the place of sons for the Israelites. God’s action is echoed, in Leviticus, where the Law describes how only a family member could “ransom” a family member who was enslaved by a “foreigner..”

Today he “redeems us from the house of bondage” just like he did in Egypt, only now it’s the devil who holds us and baptism and the Eucharist makes us his family, “bought with a price” paid in the blood of his own firstborn son.

But God is far more powerful than Satan. Why did he do it this way? Why didn’t he take us back by force?

Because God is love, and love never forces itself. God never overpowers us and makes us love him, he always woos and wins us instead.

We will win over our people in our time only by wooing and winning them, also. They will only follow if we suffer.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity