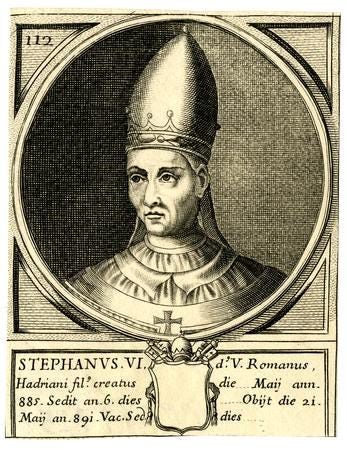

Today in Papal History, the 110th pope of the Roman Catholic Church – Pope Stephen V (VI) – died after a 6-year reign.

Stephen, who immediately preceded Pope Formosus of Cadaver Synod fame, had been elected to follow Pope Adrian III, who ended up being canonized literally 1000 years later (by Leo XIII in 1891).

Apparently the Roman clergy and citizens wanted two holy guys in a row, so Stephen ended up getting the nod.

Late-9th Century Rome was a pretty depressing place. Although Stephen’s family was wealthy and were members of the Roman aristocracy, famine, the neglect of infrastructure, and a literal plague of locusts were hitting the Eternal City by the time of his election, so he largely spent his years feeding the poor, ransoming slaves, and restoring Rome’s churches.

And what’s more, he did it with family money, because the papal treasury was bare.

There’s relatively little else of note about the life of Stephen V, but an interesting bit about the Roman numeral following his name is worth mentioning. The qualifier “(VI)” typically follows the “Stephen V” on papal lists, given the unusual circumstances of a prior Pope Stephen nearly 150 years prior.

When the original Pope Stephen II was elected, he ended up dying before being officially installed as pope. As a result, this “Pope-elect Stephen II” has typically been omitted from modern lists, with the next Stephen being referred to as “Pope Stephen II”.

And so, annoying or confusing as it may be, we give a nod to Pope-elect Stephen II by putting the next Roman numeral in parentheses after Popes Stephen II, III, IV, V, and VI.

Fast forward six centuries, and we find that September 14 also marks the death of another pope – the only Dutchman to sit in the Chair of Peter, as it turns out.

Adrian of Utrecht was elected in January of 1522 to be the 217th successor of St. Peter, following the notorious Leo X and being tasked with trying to clean up the mess he’d made in Germany and beyond.

Adrian, who is one of just two popes in the modern era who chose to keep his baptismal name upon election (Marcellus II being the other), was a man of humble stock who had risen through the ranks of the Church on his own merits – a rarity in those days – and with a bit of “right place, right time” luck.

From our entry on Pope Adrian VI in Popes in a Year:

Despite being born into a poor Dutch family, Adrian of Utrecht gained prominence through his education at the University of Leuven (Belgium). He went on to teach there, and was so beloved that his two most popular books were initially published by his students without his knowledge, simply by compiling their notes from Adrian’s lectures. In 1506, Emperor Maximilian was like, “Yo, Adrian,” and asked him to tutor his grandson, the future Emperor Charles V, successor of King Ferdinand of Spain. Before Adrian was made pope, the humble professor would be made Bishop of Tortosa, Grand Inquisitor of Spain, red-clad cardinal of the Church, and Regent of Spain.

Adrian rode his support from Charles V into the papacy to become Pope Adrian VI – technically as a compromise candidate in order to avoid a Medici being elected on the one hand, and a pawn of King Henry VIII on the other.

To Adrian’s credit, he did his very best to reform all of the errors and idiocies of Pope Leo X, who hadn’t so much ushered in the Protestant Reformation as he was simply too negligent and imprudent to prevent it from happening.

At any rate, Adrian’s efforts by that point were like a single beaver trying to dam up the Amazon River. The damage had already been done, so Adrian VI, hampered further by an immovable College of Cardinals and his predecessor spending all of his money, was unable to accomplish much.

Adrian VI died less than two years into his reign at the age of 64. He’s now buried in the Church of Santa Maria dell’Anima in Rome.

250 years after Pope Adrian VI’s death, papal intrigue abounded.

Well, it was technically papal property intrigue – the French enclave of Avignon, to be precise.

Avignon, as many readers of TiPH will recall, is a rather vital portion of papal history given that popes resided there for 70 years in the 13th and 14th Centuries while under the thumb of French kings. It was also later a refuge of several antipopes during the Western Schism in the late 1300s and early 1400s.

The impregnable Palais des Papes (“Palace of the Popes”) in Avignon, built by Pope Benedict XII and Pope Clement VI during their respective reigns.

The impregnable Palais des Papes (“Palace of the Popes”) in Avignon, built by Pope Benedict XII and Pope Clement VI during their respective reigns.

Even once the papacy had moved back to its rightful place in Rome – aided by St. Catherine of Siena telling Pope Gregory XI (charitably, of course) to grow a pair – it still belonged to the papal states as part of the popes’ domain.

Until the French Revolution hit.

Today in Papal History, in fact, marks the very date in which Avignon declared its independence from Rome and expressed a desired to be annexed by France. Edward Kolla, writing in Law and History Review, recounts the story:

Civil strife between partisans of the pope and those who advocated union with the French nation ensued in both Avignon and its adjacent but politically separate neighbor, also under papal rule, the Comtat Venaissin. After much violence, political and legal wrangling, and a plebiscite (a vote of all the citizens, basically) conducted over the summer of 1791 that according to French officials showed union to be the sovereign choice of the people, the National Assembly in Paris decreed the union of Avignon and the Comtat with France on September 14, 1791.

And finally, Today in Papal History marks the occasion of Pope St. Paul VI canonizing St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, the first American-born saint.

Elizabeth, born in New York City in 1774, was originally a wife and mother, having converted to Catholicism only after discovering it in Italy following her husband’s untimely death from tuberculosis – which made her a widow at age 27 with five young children.

She endured various hardships over the ensuing years, but in spite of them cared both for her children and for those in need around her. She was responsible for the founding of multiple schools, and ultimately helped found the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph in Emmitsburg, Maryland in 1809. She continued to cultivate her community and schools over the next 12 years, but fell ill and died in 1821 at just 46 years of age.

Her cause for sainthood was officially opened by Cardinal James Gibbons of Baltimore in 1882, she was beatified in 1959 by Pope St. John XXIII, and was canonized on September 14, 1975 by Pope St. Paul VI.

According to the National Women’s History Museum, these were the miracles attributed to her intercession – medically inexplicable occurrences that are prerequisites for beatification and canonization:

The first miracle attributed to Seton happened in New Orleans, where Sister Gertrude Korzendorfer made a full recovery from pancreatic cancer in the 1930’s. Four-year-old Ann Theresa O’Neill was also cured of acute, lymphatic leukemia in 1952, after Sister Mary Alice prayed to Seton. Finally, Carl E. Kalin was given a few hours to live in 1963, when he was brought to St. Joseph’s Hospital in New York. He was diagnosed with meningitis of the brain and was in a coma. The Sisters of Charity of the New York chapter visited Kalin, and placed a piece of Seton’s bone, known on a relic, on him and prayed to Seton. Kalin woke a few hours later.

In his homily at her canonization Mass, Pope St. Paul VI said this about the USA’s first native citizen to be raised to the altars:

Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton is an American. All of us say this with spiritual joy, and with the intention of honoring the land and the nation from which she marvelously sprang forth as the first flower in the calendar of the saints. Elizabeth Ann Seton was wholly American! Rejoice, we say to the great nation of the United States of America. Rejoice for your glorious daughter. Be proud of her. And know how to preserve this fruitful heritage of hers. This most beautiful figure of a holy woman presents to the world and to history the affirmation of new and authentic riches that are yours: that religious spirituality which your temporal prosperity seemed to obscure and almost make impossible. Your land too, America, is indeed worthy of receiving into its fertile ground the seed of evangelical holiness. And here is a splendid proof-among many others-of this fact

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity