SAINTS & ART: St. Francis de Sales anticipated the Second Vatican Council’s focus on the universal call to holiness, in all states of life.

I’m featuring St. Francis de Sales (1567-1622) among this month’s “Saints in Art” because Dec. 28 was the 400th anniversary of his death. (I have yet to understand why his feast falls on Jan. 24, except that Dec. 28 is preempted by the older Feast of the Holy Innocents).

So, why bother with somebody who died 400 years ago? What does he have to say to people today?

A lot.

One of the most important elements in the spirituality of St. Francis de Sales is its focus on holiness as everybody’s concern. His Introduction to the Devout Life — one of the most important classic works in Catholic spirituality — was not written for religious. It was written for average Catholics, in a way that still makes it readable by the average Catholic. Introduction was written not for people planning to renounce the world, but for people who would continue to live in the world while striving to become holy.

That was quite revolutionary for its time. Yes, Scripture tells us to “be ye holy as your heavenly Father is holy” (Matthew 5:48) but, by a certain time, spiritual perfection came to be considered the province of a select few, while avoiding sin seemed to be the preoccupation of the vast majority. St. Francis de Sales rejected that idea.

Perhaps Francis de Sales does not seem so revolutionary to us, given that we have lived with the Second Vatican Council’s renewed focus on the universal call to holiness. As the Council taught, the “Lord Jesus, the divine Teacher and Model of all perfection, preached holiness of life to each and every one of his disciples of every condition” (Lumen gentium, no. 40). But in 16th- and 17th-century France, that was different.

Another way that Francis speaks to people today is the “despair” some call the crises of conscience he suffered in his youth. Francis was deeply worried about his salvation; it was only after invoking the Blessed Virgin Mary that he realized “God willed good for him.”

In today’s Church of Nice, that might not seem so remarkable (though I suspect more people doubt that than let on). But in the 16th century, stalked by plague, war and high mortality, Francis was not alone in those fears. The question is how one dealt with them. Martin Luther, for example, chose to invent his own church.

This concern about one’s salvation also fed into the point raised above, i.e., that God wants us to be holy. The Protestant Reformers regarded holiness as unattainable. For Luther, God’s grace does not change me but how God looks at me. His analogy is that man is like a pile of dung and God’s grace, snow. Snow covers the dung, but it’s still dung: don’t go tiptoeing through the tulips barefoot.

Yet, among Protestants, Luther was the optimist. Francis de Sales lived near Geneva, the headquarters of Jean Calvin, a religious fanatic who deemed mankind a massa damnata (damned mass), mostly predestined to hell, and human nature “utterly depraved.” With Protestants pounding that warped vision of man, one was content escaping damnation rather than aspiring to spiritual heights.

Born in 1567 to a noble family in Savoy, that part of southeastern France near the Swiss border, Francis was prepared for a legal and political career, studying at the University of Paris and law at the University of Padua. Though his family wanted him to make a political and legal career, Francis felt called to the priesthood. He was ordained in 1593.

Because Calvin had turned Geneva into a theocracy, many Catholics now lived in Savoy, while Calvinists were influential in the area. Francis set out on the task of converting Calvinists. He preached and proselytized. When people wouldn’t listen, he slipped tracts under their doors, written in his graceful but solid style. Gradually, he began having an effect.

When the bishop of Geneva died, he became its new bishop in 1602. It should be noted, however, that he never lived in the city. Because the Canton of Geneva repressed the Catholic Church, the bishop lived in exile in Annecy — then in Savoy, now in France, about 25 miles south of Geneva.

Francis’ popular preaching inspired a widow, Jane de Chantal, who, serious about her spiritual life, asked him to be her spiritual director. In the process was formed a friendship that led both to deeper mystical insights and led Jane to found a new religious order, the Sisters of the Visitation. Like Francis, she has been canonized a saint. His spirituality subsequently influenced other religious congregations, e.g., Don Bosco in the late 19th century and his Salesians.

Francis was active in reforming his diocese and personally in evangelizing his far-flung and remote flock, spread over the slopes of the western Alps. At the same time, he carried on active correspondence with people who sought his spiritual direction as well as his own writing. Introduction to the Devout Life and Treatise on the Love of God are two of his very readable masterpieces. Why not try them?

Francis died of a stroke in 1622. He was canonized in 1665.

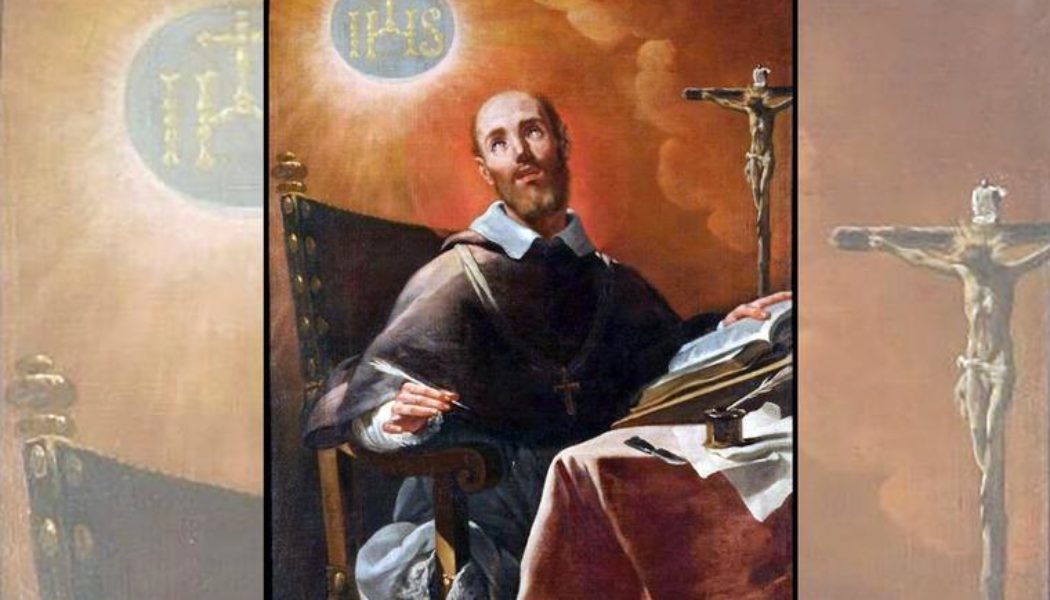

Our saint is depicted in art by Francisco Ruiz de la Iglesia (1649-1704), a 17th-century Spanish Baroque painter with affiliations to the Spanish court. His works included religious themes and portraits. “San Francisco de Sales,” dating from the 1690s, is both. The saint is depicted diligently at his desk, writing. There’s enough paper and quills. He’s caught in a moment of thought, looking beyond himself, while behind the radiation of Jesus’ holy name (IHS) inspires him. Lest anyone think the doctrine is his, a crucifix stands prominently next to his writings, reminding us that the focus is on Christ. The saint is still relatively young — he was only 55 when he died.

The painting is held by the Spanish National Sculpture Museum in Valladolid.