The feeding strategy of woodpeckers requires two specialized adaptations: one understood by the whole world, the other known to but a few students of birds.

The first is the ability to hammer into wood and throw aside the chips, whether excavating a nest cavity or digging for tasty beetle grubs. The woodpecker’s head strikes with at least 1,000 times the force of gravity (1,000 g), yet the bird suffers no apparent harm. By contrast, any human who experienced a 100 g impact would surely die. So why don’t woodpeckers damage their brains, or at least get headaches?

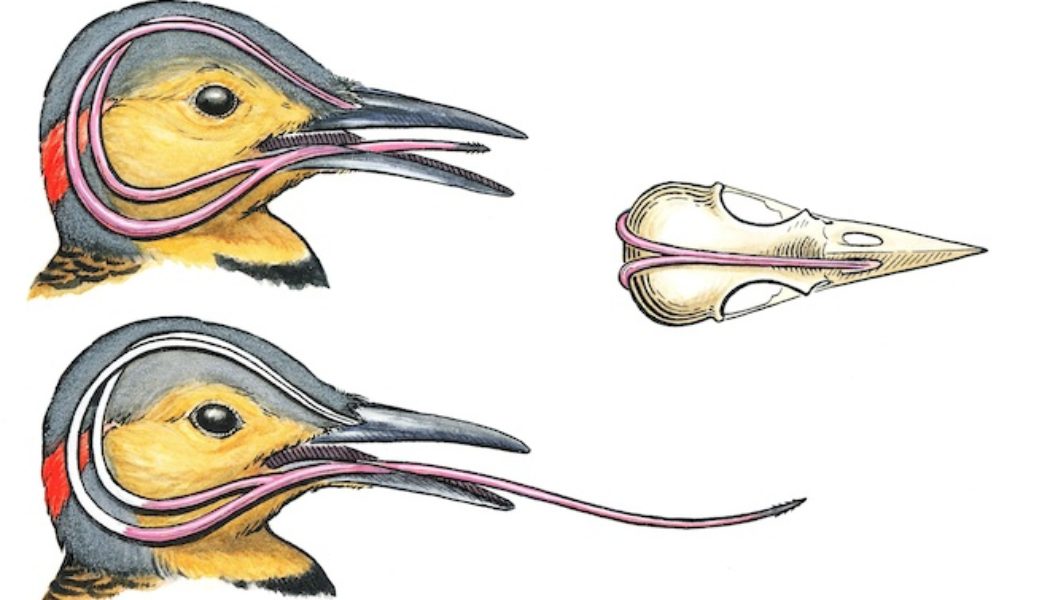

Several factors contribute to the bird’s shock-absorbing capability. One is a self-sharpening, chisel-like beak that moves into wood rather than stopping abruptly. (See the illustration above.) Another is strong neck muscles. Reduced space in the cranium also helps, by keeping the brain from sloshing around. And the orientation of the brain itself is important, since it allows the force to be spread over a larger surface area.

Researchers studied Great Spotted Woodpeckers

Using high-speed cameras, torque sensors, and scanning electronic microscopy, researchers at Beihang University, Beijing, China, recently studied Great Spotted Woodpeckers. In parts of the bird’s skull and lower mandible, they discovered micro-modifications in bone structure that allow sliding (deformation) that helps absorb the impact of pecking. They also found that the tissue layer covering the woodpecker’s upper beak was longer than the layer covering the lower beak, while the boney structure of the lower beak was longer than the upper. This mismatch, the scientists believe, allows energy to be directed through the lower beak and away from the braincase.

The second adaptation is an unusually long tongue. Since a woodpecker typically probes crevices that prevent us from seeing the tongue, its length is one of the best-kept secrets of birdlore. Our best opportunity to see a woodpecker’s tongue is when a flicker feeds on ants at an anthill.

Woodpeckers are omnivores that feed on insects, spiders, and other arthropods, as well as nuts, fleshy fruits, and sap. A specialized tongue isn’t needed to eat nuts and other fruit, but it’s a great adaptation for reaching into narrow openings to extract tasty morsels. This is especially true when a woodpecker taps into an ant run or an insect gallery.

Photo: Red-bellied Woodpecker using its long tongue to reach food

Woodpecker tongues vary, but most are long and narrow and have an assortment of backward-projecting barbs near the tip. A woodpecker sometimes uses its tongue as a spear, penetrating and then dragging insects to the surface, but the bird probably uses it more often as a rake, extending it into holes and then retracting it. Woodpeckers also produce large amounts of sticky saliva that coats the tongue, enhancing their ability to capture insects.

A complex of cartilage and bone called the hyoid apparatus supports the tongues of all vertebrates. In birds, the small hyoid bones and cartilage extend to the tip of the tongue.

Two horns of the hyoid, each consisting of narrow bones and cartilage, project backward and laterally from the base of the tongue. In most birds, the horns of the hyoid terminate on either side of the trachea, but in woodpeckers they continue farther back. Muscles attached to the hyoid move the tongue; when the hyoid apparatus is moved forward, the tongue is extended. The greater the length of the hyoid horns, the farther the tongue can be extended. The tongue can be several times longer than the bill.

Storing a long tongue

A problem with a long tongue is where to store it when it’s not in use. Woodpeckers came up with a creative solution. Rather than terminate below the skull, the hyoid horns continue over the back of the skull, just under the skin, and continue over the top of the skull. The two horns then join, extending forward as necessary — sometimes inserting into the right nostril.

Downy, Hairy, Red-bellied, and Red-headed Woodpeckers all feed on insects and other organisms, as well as fruit. The birds’ tongues are intermediate in length and have varying numbers of barbs.

Flickers, which likely eat more ants than any other North American bird, have a flattened tongue with few barbs and rely on sticky saliva to capture insects. Flickers have the longest tongue of our woodpeckers and commonly visit anthills, where they move their tongue in snake-like fashion over the surface.

Surprisingly, Pileated Woodpeckers have a relatively short tongue. They typically excavate deeply into trees, looking for insects — especially carpenter ants, which the big birds seem to relish. Sapsuckers have the most unusual tongue of all woodpeckers: it’s short and terminates with brush-like bristles that are adapted for feeding on sap. The bristles absorb sap through capillary action.

Sapsuckers typically drill neat rows of closely packed tiny wells, often a quarter-inch in diameter. Besides sap, the birds feed on insects, and especially relish those attracted to the sap wells.

Adaptations to prevent brain damage from a life of hark knocks serve woodpeckers well, and their long tongues permit the capture of hidden morsels of food. The clever adaptations are further examples of the amazing lives of birds.

Read it yourself

You can read the study described in this article, Why Do Woodpeckers Resist Head Impact Injury: A Biomechanical Investigation, in the open-access online journal PLoS One.

Learn more about woodpeckers

Why a Downy Woodpecker might have red on its crown, not nape

Six photos from the Red-bellied Woodpecker family album

Lewis’s Woodpecker wins habitat protection in Oregon

Why a normally black Downy Woodpecker might look gray

Will Red-headed Woodpecker return home?

Where to see and how to help Red-headed Woodpecker

Illustration by Denise Takahashi

Have you taken a picture that shows a woodpecker’s tongue? Share it in our photo galleries.

This article from Eldon Greij’s column “Amazing Birds” appeared in the November/December 2013 issue of BirdWatching.

Originally Published December 10, 2013

Read our newsletter!

Sign up for our free e-newsletter to receive news, photos of birds, attracting and ID tips, and more delivered to your inbox.