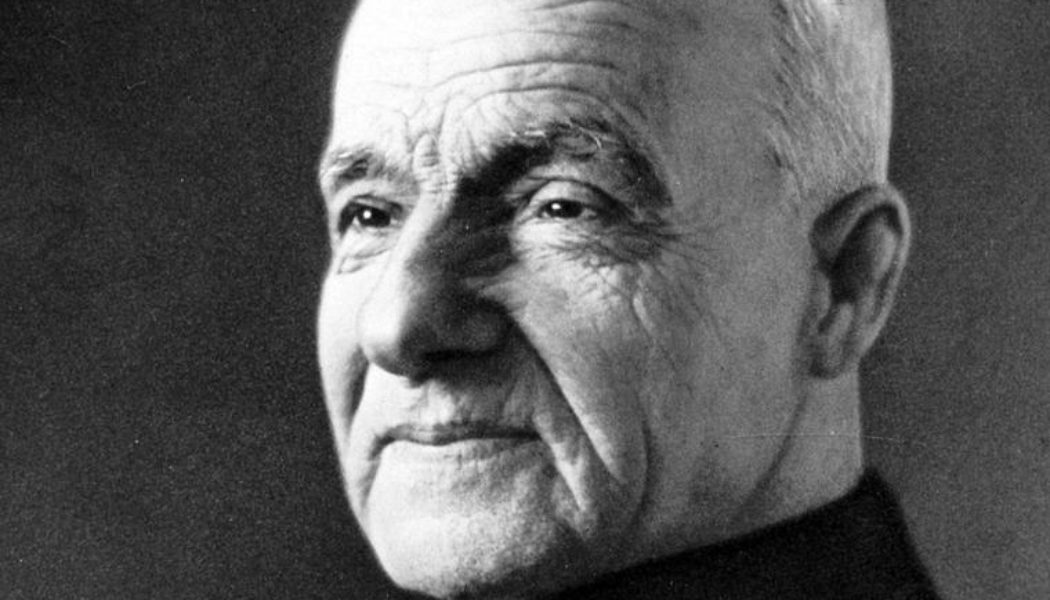

Amid his renowned humility and devotion to St. Joseph, St. André Bessette’s role as a porter reveals his profound accessibility to those in need.

Jan. 6 in the United States (except when it actually is Epiphany) can be celebrated as the optional memorial of St. André Bessette (1845-1937). In Canada, it’s an obligatory memorial on Jan. 7.

Canonized in 2010, he is known for many things. He was a powerful propagator of devotion to St. Joseph. He was the human spiritus movens behind St. Joseph’s Oratory, which towers over Montréal. He was known in his day (and in his sainthood) for the gift of healing.

He was also known for his humility. Frail and sickly, intermittently in school, he didn’t learn to read until he was in his mid-20s. He was a brother, not a priest, in the Congregation of the Holy Cross. He spent his life in supportive physical labors at a Holy Cross institution. He had a deep prayer life.

I’d like to point out one other aspect of his life that perhaps sometimes gets short shrift: his accessibility.

Among what we would today call the “support functions” Bessette performed for the Holy Cross priests and brothers was that of porter. “Porter” here does not refer to the minor order on the way to the priesthood suppressed in 1972 by Pope St. Paul VI in Ministeria quaedam. It refers to a function in many institutions: doorkeeper.

“Doorkeeper” in the United States often transmogrifies into “gatekeeper,” which means the person charged with keeping other people out. Porters are much more common in Europe, and not just in religious institutions. When I was at the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin in Poland, for example, I made acquaintance with many of its porters. They were men who tended the door — part security guard, part guide, part information desk.

Porters exist in many religious houses though, with declining vocations, many are replaced by hired secretaries. Porters do not just keep the door. They connect people to others in the house. They receive Mass and prayer intentions. They dole out charity to the needy. And they listen.

I remember sitting once some years ago in the entrance hall to St. Francis Friary, a Franciscan church across the street from New York’s Penn Station. In that spot of mass movement, the friar-porter at the door helped people, took Mass intentions, handed out bread or some cash to the homeless, and listened to people with various problems and degrees of problems.

Seventeen years ago, I wrote a book review in these pages of Joel Schorn’s book about Padre Pio, Solanus Casey and André Bessette (where I first heard of him). The book was entitled God’s Doorkeepers. Granted, Padre Pio was not so much porter of San Giovanni Rotondo as much as doorkeeper of the Kingdom of Heaven through his confessional ministry, but Solanus Casey and Bessette both performed the humble task of house porter.

And both men were besieged because their reputations for holiness preceded them. And while by perhaps today’s standards some might think those encounters were brief, it’s clear that the queues who waited for them considered them profoundly meaningful and often spiritually rejuvenating.

Little brother André Bessette was something that bigger figures in his congregation were often not: he was accessible. You didn’t necessarily need an appointment. You didn’t have to “call the rectory” to find time to schedule a talk. He met people as they were where they were and many — probably most — went away better for the encounter.

It’s said that our world suffers today from loneliness. In a world of 8 billion people, many of them can’t find somebody else to talk to. To share joy or sorrow with. To simply receive a hello or a smile, much less counsel in the challenges of human life.

Porters like André Bessette and Solanus Casey — in addition to all the other wonderful things they did as a result of the good God began in them — met those needs, those very human needs. That is a virtue: the virtue of accessibility.