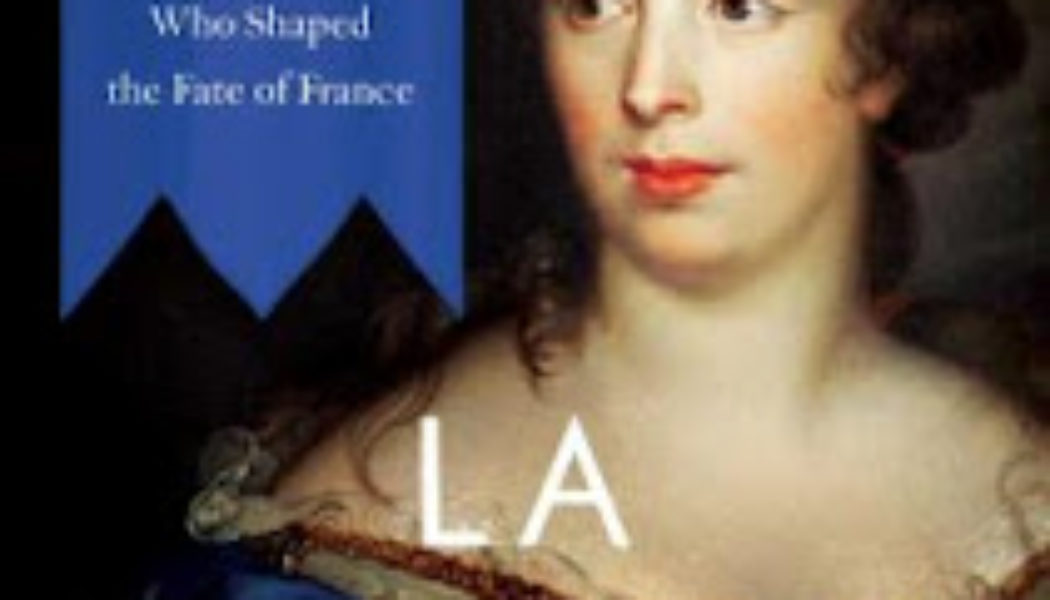

From Pegasus Books with the double subtitle: The Life of Marie de Vigneron–Cardinal Richelieu’s Forgotten Heiress Who Shaped the Fate of France:

A rich portrait of a compelling, complex woman who emerged from a sheltered rural childhood into the fraught, often deadly world of the French royal court and Parisian high society—and who would come to rule them both.

Married off at sixteen to a military officer she barely knew, Marie de Vignerot was intended to lead an ordinary aristocratic life, produce heirs, and quietly assist the men in her family rise to prominence. Instead, she became a widow at eighteen and rose to become the indispensable and highly visible right-hand of the most powerful figure in French politics—the ruthless Cardinal Richelieu.

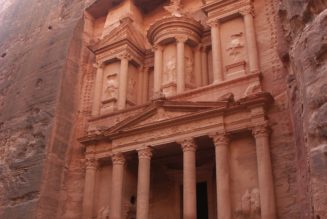

Richelieu was her uncle and, as he lay dying, the Cardinal broke with tradition and entrusted her, above his male heirs, with his vast fortune. She would go on to shape her country’s political, religious, and cultural life as the unconventional and independent Duchesse d’Aiguillon in ways that reverberated across Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

Marie de Vignerot was respected, beloved, and feared by churchmen, statesmen, financiers, writers, artists, and even future canonized saints. Many would owe their careers and eventual historical legacies to her patronage and her enterprising labor and vision. Pope Alexander VII and even the Sun King, Louis XIV, would defer to her. She was one of the most intelligent, accomplished, and occasionally ruthless French leaders of the seventeenth century. Yet, as all too often happens to great women in history, she was all but forgotten by modern times.

La Duchesse is the first fully researched modern biography of Vignerot, putting her onto center stage in the histories of France and the globalizing Catholic Church where she belongs. In these pages, we see Marie navigate scandalous accusations and intrigue to creatively and tenaciously champion the people and causes she cared about. We also see her engage with fascinating personalities such as Queen Marie de Médici and influence French imperial ambitions and the Fronde Civil War. Filled with adventure and daring, art and politics, La Duchesse establishes Vignerot as a figure without whom France’s storied Golden Age cannot be fully understood.

While I’m not quite sure that the Duchesse d’Aiguillon “shaped the Fate of France”, she certainly had a great impact on the Catholic Church in France, French Canada (Quebec), and missionary fields around the world. The impact of the French Revolution kind of limits how much her political and social efforts could shape France’s fate/future. Slightly hyperbolic, but perhaps indirectly she did by supporting the monarchy against the Fronde and Mazarin so that King Louis XIV ruled absolutely, giving the later French revolutionists something to rebel against!

After the death of Richelieu, who made her his principal heir, she retired to the Petit-Luxembourg, published her uncle’s works and continued her generous benefactions to all kinds of charities. She carried out the Cardinal’s last request by having the church and the college of the Sorbonne completed, as well as the Hôtel Richelieu, which has since been converted into the Bibliothèque Nationale. The great Fléchier was charged with pronouncing her funeral oration, which is regarded as one of the masterpieces of eloquence of French pulpit oratory.