COMMENTARY: The Nativity of the Lord illuminates our lives.

What happened on Christmas night more than 2,000 years ago fundamentally and irrevocably changed the path of humanity.

“When peaceful stillness lay all over and the night was half spent, your Almighty Word, O Lord, descended from heaven’s royal throne” (Wisdom 18:14-15).

This night, God and man become one, God and man are reconciled, and God and man begin a new path in history. That is the profoundly Good News of Christianity, not just this night, but every day and every night for the past more than 2,000 years.

It’s hard to comment on the readings of Christmas because, by tradition, there are three different Christmas Masses: at midnight, at dawn and during the day. To them has been added a vigil Mass for the evening of Christmas Eve.

The Gospel readings for the Masses at midnight and dawn come from Luke. Midnight Mass (Luke 2:1-14) features the decree of Caesar Augustus announcing a census that provokes Joseph and Mary’s trip to Bethlehem, her delivery after an unsuccessful quest for lodging, and the announcement of the angels to the shepherds. In the Mass at dawn (Luke 2:15-20), the shepherds make their way to the place where the Child lay.

Mass during the day moves back from the events directly surrounding Jesus’ birth to his preexistence as the “Word of God” from all eternity. The Gospel featured is the Prologue of John (1:1-18), which affirms the truth of this day: “The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory.” It also gives a final, Advent-in-the-rear-view-mirror salute to John the Baptist, who “came to testify to the light” that “was coming into the world.”

The vigil Mass repeats the previous Sunday’s Gospel: Matthew’s account (1:18-25) of Joseph’s dream by which God reassures him of Mary’s integrity and by which he “took his wife into his home.” Matthew’s Infancy Narrative does not mention the shepherds but does mention the Three Wise Men, the Gospel we will hear for Epiphany. The celebrant of the vigil Mass can use the long form of Matthew’s account (1:1-25), which prefaces the account of Joseph’s dream with Jesus’ genealogy, divided into three sections of 14 generations each, split at key moments of Jewish history: its origins with Abraham, the kingship of David, the Babylonian Exile, and the birth of Jesus. Of special interest in Matthew’s genealogy is the mention of five women — Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, she who “had been the wife of Uriah” (Bathsheba), and Mary — pregnancies that were all in some sense “out of the ordinary” (e.g., foreigners, the fruit of adulterous murder, and a Divine conception).

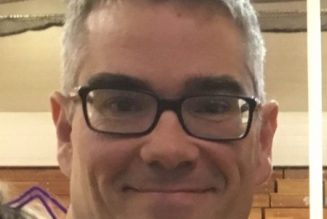

The Solemnity of the Nativity of the Lord is illustrated by the 18th-century French painter Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre (1714-1789). This oil painting is held in a private collection.

Nativity testifies to Jesus Christ, that the “true Light, which gives light to everyone, was coming into the world” (John 1:9). The center of illumination in the painting is the Christ Child. Virtually all the light in the painting emanates from him. (True, there is a full moon in the sky on the upper right, but Jesus is the true source of illumination in the painting.) All the dramatis personae are revealed in his light, with the greatest light reflected on his mother, Mary, whose body, in comparison with the others, is almost totally illumined by her Son — not just an artistic but a theological statement. Joseph, as usual, occupies a humble, back-row position on the right, his body configured in a cross between adoration and readiness to action. Two male shepherds and two women appear on the left. All of creation is gathered here: the plant world (hay), the animal world (the brown cow on the lower right, the sheep — “Lamb of God?” — on the lower left), the human world (the Holy Family and the shepherds), the angelic world (three cherubs adoring from above), and God himself. The eyes of all persons but one’s is on the Child; the highest angel looks heavenwards, from whence “Your Word … descended from heaven’s royal throne” amidst the Most Holy Trinity.

Despite the universal attendance roster at this manger, the inhospitable welcome of the Savior of the world is underscored: Against the warmth of his light stands the exposed nature of this manger, a pillar supporting its thatched wood roof that reveals its openness to the outside world, including the dark, rough topography on the left.

“The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light. Upon those who dwelt in the land of gloom, a light has shown.” So does Isaiah inform us in the first reading (Isaiah 9:1-6) at midnight Mass. Pierre captures that great light shining amidst gloom in his Nativity. What at first glance seems a standard Nativity scene can also be read in a theologically sophisticated way.

Pierre won the grand prize of the Royal Academy of Painters when he was but 20, and from 1770 until his death, two months before the storming of the Bastille, he was royal painter for Louis XV and Louis XVI.

May we ever reverence the Light of the World, at Christmas and always.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity