Will Jesus Christ really come again? It seems like we believe that less and less. But the faith doesn’t make any sense if it isn’t true, as we see on the Second Sunday of Advent Year B.

“We wait in joyful hope for the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ,” we pray at Mass. But what does that mean?

We aren’t waiting for Christmas — not really. That already happened. What we wait for now is for Jesus to come again. Literally. From the sky. With angels. But do we really believe that after all these years?

If you’re like me, you might think — maybe not. If you’re like me, you might suspect yourself of using Christianity as an emotional crutch to prop up your spirits rather than as a rod of truth pushing you to radical change, and accept that God loves you, a lot, in Christ while struggling with elements of it that sound fantastical.

You may think: We know so much more compared to early Christians. We once thought we were unique, that God made the world for us and then came and joined us in the charming Christmas story — but now we’re not so sure that it’s all true. Or, truth be told, we may be pretty sure it’s not all true. We have seen the science and we buy it: We feel imperfectly made and truly insignificant in a universe that the NASA telescope is proving is even more vast than we knew. Credible Air Force reports of UAPS — formerly known as UFOs — make us feel weak, exposed and vulnerable.

The comfortable story about God loving us alone and coming to die for us feels less and less like a rock solid certainty and more and more like a sweet fable. And if we’re honest, we might admit that the Second Coming seems fanciful at best — or the archaic remnant of an ignorant age, a deus ex machina device to tie up loose ends of salvation history our theology can’t account for.

But the figures we meet in Sunday’s readings were not gullible people seeking psychological comforts.

Start with St. Mark himself. He is doing something audacious and subversive with Sunday’s Gospel, starting with: “The beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, son of God.”

Bishop Robert Barron likes to point out that Mark is challenging the Roman empire. “Good news” is our translation of “evangelium.” When a new land was conquered by Rome, Caesar “sent evangelists ahead with the good news” that the people were now Romans, and belonged to Caesar, who, since Augustus, carried the title “Son of God.”

Mark is making the radical claim that Jesus Christ, not Caesar, is the Son of God and that the land isn’t ultimately the emperor’s — it belongs to a criminal he crucified.

He didn’t say this to provide a helpful psychological crutch for Christians in a hard time. Saying what he said is like telling your boss that you will use your department to support the competition; it’s like telling your coach that you plan to help the other team score; it’s like telling the cop that you have laws of your own that you choose to follow.

The next non-comforting voice we hear is John the Baptist’s.

Like Mark, John’s message was a radical repudiation of the status quo of his time. Only John wasn’t just taking on the Roman empire — he was taking on the religious leaders of his time, too. He said, “One mightier than I is coming after me. I am not worthy to stoop and loosen the thongs of his sandals. I have baptized you with water; he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit.”

And he was rewriting even more than the political order; he was rewriting salvation history — announcing a New Exodus from the banks of the Jordan River. He must have been supremely irritating to the religious and secular leaders of the city, who saw that “all the inhabitants of Jerusalem were going out to him” to receive his “baptism of repentance.”

But he didn’t back down. John didn’t give people reasons to feel good: He gave them reasons to change their lives. And he wasn’t comforting: He was formidable and foreboding.

What is the difference between John the Baptist and Mark and us?

John the Baptist was a special prophet chosen by God and given a special prophetic charism — “among those born of women there has risen no one greater than John the Baptist,” Jesus said.

But Mark was not a prophet in that sense. He was more like you and me: A baptized Christian who knew that Jesus Christ rose from the dead, the kind of Christian Jesus meant when he said: “He who is least in the kingdom of heaven is greater” than John.

And what makes Mark and you and I greater than the prophets — and just as willing to face down the powers of our day? Simple: We share the resurrected life of Jesus.

Mark believed he had a greater king than Caesar because Jesus had risen from the dead, Mark believed Jesus would truly come again, because his friends saw Jesus ascend, and Mark was unafraid because he had received the Eucharist.

If Jesus didn’t rise from the dead, Christmas is exactly what the world thinks it is: A warm and comforting story to indulge in when the weather gets cold and we need a break from reality. But if Jesus really did rise from the dead, Advent is what the Church says it is: A wake-up call telling us in no uncertain terms that we had better radically change our lives or we will find ourselves fighting for the wrong king, playing for the wrong team, and living by the wrong rules.

A number of works take a deep dive into the evidence for the Resurrection. The Resurrection of the Son of God by N.T. Wright is a thorough look at what we know and it comes to a powerful conclusion: This is history, not a fairy tale. Jesus really did rise from the dead.

Dale Allison Jr. at the Princeton Theological Seminary challenges Wright and scores some points as he reviews the evidence, parsing wishful thinking from history in The Resurrection of Jesus: Apologetics, Polemics, History. But ultimately even Allison’s book shows not just that the Resurrection is possible — but that many Catholic apparitions are too, and that Jesus uniquely touches all the hallmarks of the most powerful apparitions.

But maybe the best proof of the resurrection is a book that doesn’t even intend to defend it. Tom Holland’s Dominion shows how Christianity rewrote morality, human dignity, science, and culture, radically changing even non-believing countries.

So when we ask if there will be a Second Coming, the question we are really asking is: “Jesus Christ said he would rise from the dead and then did. He said he would change the world, and he did. He also said he would come again. Will he?”

I’m going to go out on a limb and say he will.

And that means our job now is to get ready for him to return.

People in the early Church thought it would happen in their lifetimes. Not so fast, says Peter in our Second Reading. “Do not ignore this fact,” he said, “that with the Lord one day is like a thousand years and a thousand years like one day.”

It will happen though, he said. “The day of the Lord will come like a thief, and then the heavens will pass away with a mighty roar and the elements will be dissolved by fire, and the earth and everything done on it will be found out,” he wrote, and asked: “Since everything is to be dissolved in this way, what sort of person ought you be?”

His answer is to “conduct yourself in holiness and devotion.” A great place to dedicate yourself to a Christian life that does just that is at Mass, especially after receiving communion.

Vast universe or not, UAPs or not, the one who is risen from the dead will come again, and we should “be eager to be found without spot or blemish before him, at peace.”

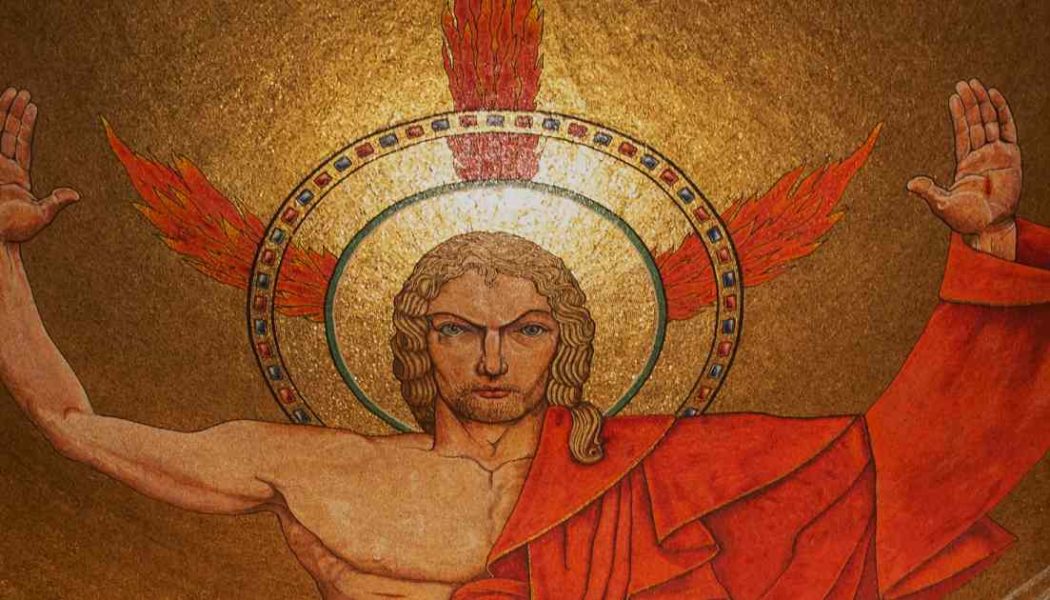

Image: Christ in Majesty mosaic, National Shrine of the

Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C.

Jan Henryk Rosen, Wiki-media