The Congregation for the Clergy published last week the “Instruction for the pastoral conversion of the parish community in the service of the evangelizing mission of the Church.” It is not a revolutionary instruction, although many looked to that document for clues of a revolution. They were disappointed when they were not able to find any. This is the paradox of Pope Francis’ pontificate.

The Congregation for the Clergy published last week the “Instruction for the pastoral conversion of the parish community in the service of the evangelizing mission of the Church.” It is not a revolutionary instruction, although many looked to that document for clues of a revolution. They were disappointed when they were not able to find any. This is the paradox of Pope Francis’ pontificate.

The conclave elected Pope Francis with the mandate of carrying out reforms. So, Pope Francis’ pontificate has always had to do with the idea that the Pope was called to revolutionize the Church. What does “revolutionize” mean? It means making the Church more “Council-like” (meaning, the Second Vatican Council), closer to the signs of the times, less connected with the signs of its power. This terminology is rather vague. In the end, it is hard to understand how the Church should change.

The Church has always been close to the poor, and all of its structures are about helping the poor. True, there have been corrupt people or people who perpetuated their own power. It does not mean that the Church has not worked for the poor. The many charities and activities born to help the poor prove it.

The Church has always been at the service of the faithful, with the primary goal of making the Eucharist available all over the world, and to baptize and convert in the name of Jesus. True, there were moments when the Church institution was more rigid, and the separation between the priest and the lay people seemed unsurmountable. Its depth depended on the priest’s sensitivity and circumstances. However, only the priest can consecrate the Eucharist, and priests have specific responsibilities. This has never changed.

Finally, the Church has always been missionary. Missionaries have gone to the “ends of the earth” and keep doing it. True, the anxiety to convert and ties with robust and powerful institutions sometimes made the Churchmen behave badly. It does not mean there has not been an evangelizing mission, though.

Why, then, call for a revolution? Why are people trying to take the Church where, in the end, she has always been?

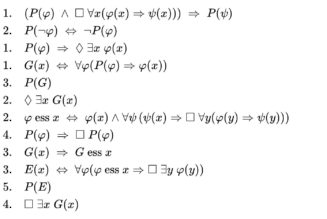

Everything is born out of the Second Vatican Council – better, out of the way the Second Vatican Council was received. This is a central issue. Did the Second Vatican Council changed radically or did it rather look at the Church in a new way, always in continuity with the tradition?

Paul VI, John Paul II, and Benedict XVI always emphasized the continuity with the Apostolic tradition. There was a new way of reading the sign of the times. This new reading did not mean that the previous teaching of the Church was invalid. Everything must be read through the lenses of tradition.

There are those who consider the need for a rupture with tradition. According to this view, the Second Vatican Council’s documents stand apart from norms and traditions. They instead build a different Church. A Church, in the end, that evangelizes without evangelizing. That has the structures to help the poor but not the institution. That speaks to the world, but without a strong voice.

It is, in the end, a paradoxical Church. It is not Pope Francis’ Church. It cannot be at all.

Pope Francis is anti-institutional and pragmatic. He has always promoted a “poor Church for the poor,” and he distrusts aggressive models of evangelization. Pope Francis does not like careerism, and for this reason, he does not like the institutions where careerism can happen. All of his reforms within the Church are aimed at addressing these three issues.

Furthermore, for Pope Francis the Church is a “holy, hierarchical mother.” Pope Francis’ observations on the role of the priests reveals that, to Pope Francis, the priest is still at the center of the village or community. Let nobody be fooled: when Pope Francis speaks about significant involvement of laypeople, and in particular of women, within the Church, the Pope is merely speaking about participation in the life of the structures and the service to the community. He is never speaking about laypeople replacing priests.

These are not slight nuances. There is an extraordinary expectation around Pope Francis as if the “Pope who came from the ends of the world” has been called to change the Church’s foundations. When Pope Francis speaks, he feeds this hope. When he comes to norms, the real Pope Francis is revealed.

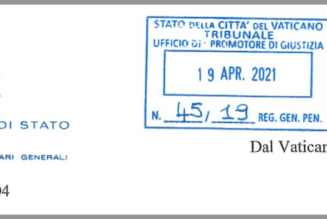

The instruction of the Congregation for the Clergy is no exception. The first part of the instruction is filled with references to the “pastoral conversion” and the need not to perceive the parish anymore as a territorial entity. The instruction even asks the parishes to change, but to do it gradually, so that the faithful are not puzzled with the changes.

The second part of the instruction is about practical application. That part merely reiterates what the Church is already doing. There was a lot of emphasis on the fact that the instruction says that even laypeople, in exceptional cases, can assist in baptisms, marriages and funerals. This is not news. There has always been the possibility to do so. In the end, the Church in Japan was for centuries under persecution and survived with no priests because she was nevertheless able to transmit the faith.

The instruction’s impact was compared to those of Amoris Laetitia and Querida Amazonia. Both of these post-synod exhortations were filled with expectations of a revolution. This revolution never took place. At least, it did not take place the way we expected.

In Amoris Laetitia, the opening to the possibility of divorced and remarried taking communion lay in a footnote. Instead, Amoris Laetitia mostly emphasized discernment, and this is a very ancient theme of the Church.

Querida Amazonia, contrary to expectations, had no mention of married priests, since that was not the center of the Synod’s discussion. The document’s goal was seeing and giving dignity to a specific reality, the Panamazonian Region, to strengthen and elevate the Latin American continent.

These documents live in a constant tension between an inspired theology and the application of norms. This tension is hard to manage and has its origins in the post-Second Vatican Council discussions. Benedict XVI, for example, noted in his letter to the Catholic of Ireland that this misconceptions brought about the setting aside of norms, and this led to a failed response to sexual abuse by Clergy.

Pope Francis is more pragmatic. He lives the moment. He does not look to a general framework. He tries to practically carry forward the pastoral conversion he has been talking about. All of his work is aiming at this goal.

Pope Francis is, however, working under a difficult situation: he is under pressure. The pressure mostly comes from those who say they are supporting the pontificate. These people will support the papacy as long as the pontiff meets their expectations.

Nowadays, the truth is that just a few want to see the Church for what it is. In that case, they should admit that history is different from the way it is told. There would be no need to speak about revolutions nor a need to generate contrasts between pontificates, cardinals or Church’s models. There would only be the Church. And this would be a real revolution.