Pillar subscribers can listen to this Pillar Post here: The Pillar TL;DR

Happy Friday friends,

This newsletter is coming to you from swinging London, where we are on a family visit. It is, sadly, a long way to come, and we don’t manage it as often as we would like.

The kid was surprisingly good on the plane ride over, as it happened, which certainly made the trip a little easier for all concerned. But gone forever are the days when trans-Atlantic jet lag was something I laughed off with two large drinks and a quick nap.

When I was in my 20s, I could bounce off an overnight flight straight onto the train into town and put in a full day at the office. Now, 20 years later, I find myself up half the night, trapped in confused, waking half-dreams. By the time dawn breaks I look and feel like one of those suspected Soviet double agents to whom the CIA used to force feed LSD before going to town on them.

It’s all worth it though, of course. It is pure joy to set our daughter loose among our extended family and friends, for whom she is still something of a novelty. Indeed, that’s the best part, really.

Quite a few of our friends here still refer to her unironically as the “miracle child,” remembering the years my wife and I waited with waning hope of becoming parents.

Our daughter is, some two and a half years later, a constant joy for me — no question. But it’s true that the “miraculous” sheen has worn off her, somewhat, just through the rub of daily familiarity.

The welcome bonus of a few weeks here in London, apart from seeing people and logging some quality time in my formerly regular pub, is the reminder of exactly how providential our daughter’s arrival was, and what a gift our family is.

It’s normal, I suppose, maybe even inevitable, to sink into the kind of easy familiarity that leads to taking even the most profound blessings for granted.

But, I think, that’s one of the great helps of regularly tracking back to where you’re from, allowing those who’ve known you best and longest to help you see your life through the long lens of your own history, rather than just the immediate quotidian present.

Speaking of the quotidian present, here’s the news.

The News

Pope Francis has revived use of the papal title Patriarch of the West, bringing it back into the formal litany of papal styles in the Vatican’s yearbook.

The ecumenical office also hinted that ditching the papal patriarchal handle would be good for ecumanism, though dropping it arguably caused some fights.

So why is Francis bringing it back now? What does it mean for relations with the Orthodox, and could this actually be all about… synodality?

—

The Catholic Church in Switzerland announced plans this week for the creation of a new national “synodality commission.”

The joint statement of the Swiss bishops’ conference and the RKZ did not offer a comprehensive picture of the new “synodality commission.” But it did say that both organizations had adopted a statute for the new body and guaranteed funding.

So, how does it compare with the controversial “synodal committee” in neighboring Germany?

You can get the whole story here.

—

This week, Pope Francis named Bishop Paul Dempsey, a 52-year-old leader of the Diocese of Achonry, as a new auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Dublin. It was a bit of a strange move.

It’s not often (though not never) that the pope takes a bishop out of leading his own diocese and installs him as an auxiliary. At first glance it might seem like a pretty pointed demotion.

So what’s going on?

You can read Luke Coppen’s expert unpacking of the situation here.

—

A former parish administrator could be in court next month, facing charges that she siphoned off nearly $700,000 from the Florida parish where she worked for more than two decades.

We’ve been doing a lot of work recently tracking cases like this — of large scale theft at the parish level — and speaking to expert investigators about how to spot it and stop it earlier, because it is an often overlooked crime wave doing serious harm to the Church in a time of diminishing resources.

—

Earlier this week, Pope Francis appointed a new bishop for the Diocese of Charlotte: Fr. Michael Martin, OFM Conv — that’s a member of the Order of Friars Minor, Conventual, if you get a little lost in the acronyms.

Martin will be the latest in the swelling ranks of religious bishops, that is those consecrated from religious institutes and societies as opposed to the secular diocesan priesthood.

Among nearly 250 Latin diocesan and auxiliary bishops in the United States, The Pillar found 17 religious orders, institutes, and apostolic societies represented.

I know what you’re asking: “But who’s in the lead? Which order has the most bishops?”

—

Vatican City’s chief prosecutor, Alessandro Diddi, has filed charges against an Italian reporter, arguing that he published confidential ecclesiastical documents and defamed the pope.

It’s not clear how Diddi, who took over as Promoter of Justice for the city state in 2022, having previously been the chief deputy, hopes to make the case stick.

The Vatican prosecutor’s office filed similar charges against two Italian journalists during the Vatileaks trial, claiming they had published confidential information. The charges were tossed out in 2016 on the grounds that the Vatican court had no authority over the Italian press.

You can read all about it right here.

The Vatican’s gambling man

It is difficult to know what to make of Alessandro Diddi’s decision to charge the man behind a well known, well read, and well informed Church news website with, essentially, doing journalism.

As we noted in our report, this isn’t the first time in the last few years his office (albeit not under his leadership) has tried to prosecute reporters for publishing leaked documents covered by the pontifical secret. It didn’t go well, Vatican City judges tossed the case and made a fairly obvious ruling that the Vatican judicial writ doesn’t run to cover the Italian press.

Perhaps Diddi thinks that since Perfetti runs a site which covers the Church exclusively, rather than a secular newspaper, different rules apply. Except they fairly obviously don’t. The content of a site doesn’t magically bring its authors or servers onto Vatican City territory.

You could, I suppose, try to raise a strictly canonical case against Catholic journalists for subverting ecclesiastical authority, but that’s not what Diddi has done. He’s pressing civil charges, citing the Vatican City civil penal code, of violating state secrecy, with a charge of lèse-majesté thrown in to boot.

I cannot see how this case possibly stands. Though, really, it would be arguably worse for the Vatican if it does. Convicting an (admittedly very unsympathetic) journalist of disrespecting the pope and exposing dysfunction and scandal in the Diocese of Rome is about the worst possible countersign the Church could send in an era supposedly committed to transparency and accountability.

Now, don’t get me wrong, Silere Non Possum is not my cup of tea. It’s written in that (typically Italian) style which blends factual reporting with often splenetic editorializing, often in the same sentence, let alone article. It’s not how I like to read or write the news, and I think often gratuitously personal attacks on the subjects of stories (including the pope) detract from the strength of important reporting.

But none of this marks Perfetti out from much, if not most, of the Italian press. And it certainly creates no obvious grounds to expect Diddi’s most recent attempt at prosecutorial overreach to succeed.

I hope I don’t need to explain to anyone my enthusiasm for the idea of an activist Vatican prosecutor, or my satisfaction when obviously criminal acts are finally treated and punished as crimes in the Vatican.

But as someone with a fairly deep track knowledge of his landmark financial crimes case, I was immensely frustrated with his decision to pursue a kind of grand unified theory of one big conspiracy, trying to tie together what were obviously separate instances of corruption by disparate actors. In doing so, some of the defendants told us, he rejected repeated offers of cooperation.

I wrote at the time that he hadn’t made that case hang together, because it just wasn’t there to be hung, and that the whole result of the nearly three-year trial would come down to whether the judges felt OK rejecting Diddi’s central thesis while still convicting individual criminal actors.

They did, but it was a hell of a gamble for the prosecutor to take — one he’s doubled down on by appealing his own win and asking a higher court to vindicate his one-big-conspiracy theory.

This is the great problem with Diddi: he seems addicted to long-shot indictments, often with more than a whiff of attempted intimidation about them.

In addition to pressing charges against Perfetti, Diddi previously filed notice he was considering reviving a threatened prosecution of Libero Milone, the former Vatican auditor general, after Milone announced in 2022 that he would sue the Vatican for wrongful termination.

It takes a certain kind of prosecutorial mind to threaten a case against a whistleblower filing for wrongful dismissal, but it’s even stranger when you realize that criminal case against Milone was first concocted by Cardinal Angelo Becciu — whose own conviction is Diddi’s single biggest achievement in office.

Ask around the Vatican City watercooler, and you soon hear a common set of observations about Diddi: that he is temperamental, zealous in his duty as he sees it, but above all out to prove himself.

What I hear said most often about Diddi is that he wants to keep his job, and thinks the surest way to do that is to keep as many plates spinning as he possibly can — in the headlines, if possible.

There is a kind of mad logic to that theory: if Diddi is constantly closely associated with sensitive and controversial cases, he can’t be moved without sending them crashing.

But, as the prosecutor charges from case to case, he increasingly runs the risk that he is seen as a serial bluffer and that all his big bets ending up as a very public busted flush.

Before we wrap up, I wanted to just mention again JD’s email from earlier this week about our plan to bring on our contributor Edgar Beltran as a full time Rome correspondent.

Quite a few people opted to help us get close to making it happen, including and especially existing subscribers who chose to increase their rate. Guys, seriously, thank you.

The honest truth is we didn’t quite make the number we needed. That’s what it is, and we cut our coats according to our cloth here at The Pillar — that’s what being a sustainable business means to us.

But I would just like to put a quick word in with our free readers. You know by now what we are all about. You get these newsletters twice a week, you forward around the news we report, and you understand the work we are doing here, for the good of the truth and the benefit of our Church.

You also get it, I hope, that we want to keep our news free to read, as a service to our common Catholic society, but that we aren’t a charity and we aren’t looking for handouts. We’re in the business of reporting the news, I think we deliver serious value for money, and I know Edgar will help us do more of it, better.

So I’m making a last pitch here: If you’re reading our news and think it’s worth $8, help keep it free to read for everyone else.

Thanks.

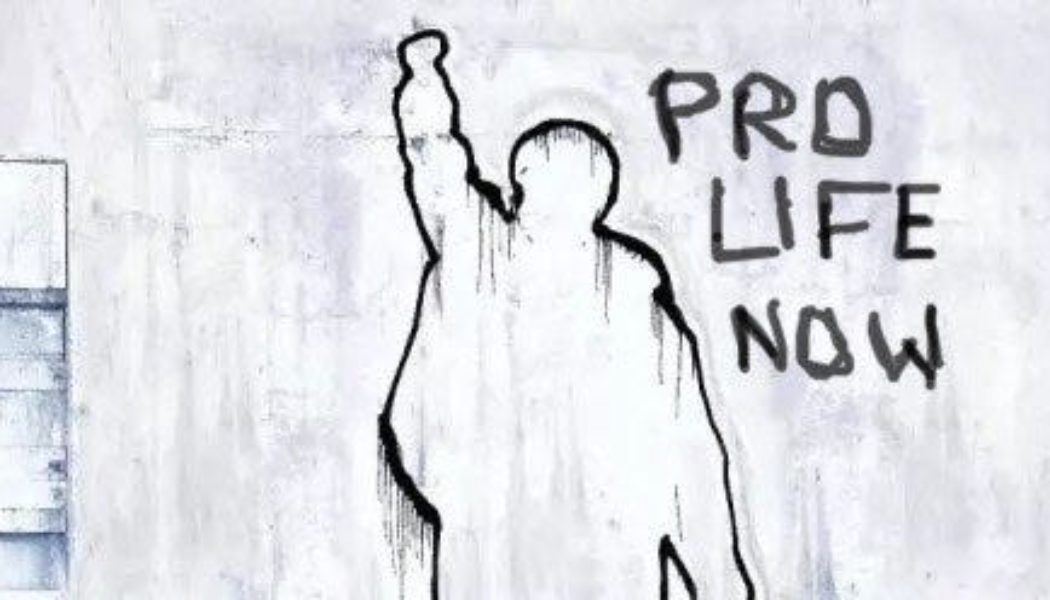

Radical reality

From my perch across the water this week, I was entertained to see the general feeding frenzy accompanying Donald Trump’s most recent statement on the politics of abortion.

Apparently, the Don is content with abortion law in the U.S. remanded to the state level, and he doesn’t want, or envisage attempting, any federal ban to mirror the Democratic commitment to legislating national total protection for the practice.

I know Trump has previously said that he thought Florida’s heartbeat bill was a bridge too far in his mind, even if it was merely a step in the right direction for some of us, so I am not sure why there was the sudden hue and cry from his erstwhile supporters.

To be sure, Trump appointed sufficient Supreme Court justices to finally consign Roe to the dustbin of history where it belongs, being as morally monstrous as it was terribly reasoned. That was the transactional calculus to which he and his pro-life supporters agreed prior to his election, and he deserves credit, I suppose, for delivering on his end of a deal on which pretty much all previous Republican presidents welched.

But while it was all the rage for a certain section of the pro-life movement to refer to Trump in office as “The Most Pro-Life President in History™” with suspicious uniformity, it was clear to anyone watching that he was nothing of the sort. He never espoused any enthusiasm, let alone commitment, to ending abortion entirely, and his record reinstituting the federal death penalty makes macabre reading.

It’s amusing, therefore, to watch some of his formerly most ardent boosters volte face now.

For myself, I’ve never seen Trump as offering the pro-life cause anything more than an utilitarian pact, on which basis I declined to judge those who chose to vote for him, in 2016 at least.

And the terms of that deal certainly bear comparison with the contemptible conduct of Joe Biden, who has publicly walked away from reservations he’d spent decades voicing about abortion as the price of his own presidency.

There is also something encouraging about seeing abortion return to the level of the states: It is my own modest observation that some of the most committed work being done for the pro life political cause, and for caring for distressed expectant mothers and their new children, is at the more local level.

Because money and power mutually attract, both tend to flow upstream, rather than down. So this local heroism is often far removed from the political machine and big dollars of the federal game

It’s become somewhat hackneyed to dissect the antics of “Pro-Life Inc.” and the undeniably big business of political opposition to abortion at the national level. And, while I can’t say I find them edifying, as long as abortion is a political issue there’s going to be a political side to fighting it, with all the big money, hot air and hair spray that comes with it.

But I’ve always revolted at the quasi-messianic zeal for Trump’s cause shown by not a few professional campaigners along the way, Catholics among them. This kind of fervor has long been a source of confusion for me, as well as distaste, though I think I have come to understand it better.

For all the sound and fury we expend talking about abortion in the United States (and abroad), we give little attention to what the practice has done to our collective consciences and states of mind.

We would all think (I hope) that if we were living in an age and place where innocent families and neighbors were being packed by the state into freight cars and shipped off to concentration camps, we’d lie down across the tracks.

Or, to take a less historical example, that if we found out there were centers dotted among our communities devoted to processing the elderly into food, we’d bring the world to a standstill.

Yet, under cover of law and “medicine,” children — not “potential human lives,” but unique persons who in many cases could survive outside the womb — are killed on an industrial scale in our midst. And what do we do?

We vote, we raise money, we campaign, we write newsletters, but do we — do I — do any of this with the panicked, outraged urgency a clear-eyed account of what’s happening would seem to demand? No. Not really.

I go about my day more or less resigned to the common taking of innocent human life as I would describe it, even as I profess to see it for what it is and to despise it. I think the knowledge of abortion should drive us insane, properly speaking. Maybe it has.

It is an irrational reality for which we self-medicate with a range of bromides: zealous political advocacy, lofty-sounding intellectualism, or (in my own case) studied cynicism.

When I was younger and working in professional politics, I considered pro-life activists of the sort who broke into abortion clinics or urgently approached the women entering them as inconvenient radicals. They were right on the merits, to be sure, but really, I thought, they were making it harder for the rest of us to push incremental, lasting change.

Nowadays, I suspect people like Lauren Handy might be the only sane ones among us, and offering the only rational response to what is happening around us.

That sense, and the impression the rest of us may have actually gone a little crazy as a coping mechanism, is only growing as “medical relief” for the terminally ill morphs into open enthusiasm for euthanizing the elderly, the autistic or depressed, and even the poor.

As the Catholic world continues to digest the Vatican’s most recent declaration on our infinite human dignity, I’m coming around to the conclusion that this dignity might require, demand even, a more radical response to our times.

Actually being authentically “pro-life” is radical, radically non-violent of its very nature, and at this point I think we should be comfortable with it being criminal — in the way Martin Luther King was made a criminal.

If that sounds crazy, it might only prove the point.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar

Comments 100

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews