Notre Dame’s first three open causes for canonization were a trio of headline-making priests (two of whom were eventually made bishops). But perhaps the most impressive Notre Dame man being considered for Sainthood was not a priest, an alumnus of the University, or even a high school graduate. Mercifully, holiness is not contingent on worldly credentials, and Servant of God Columba O’Neill (1848–1923) reached his heights while mending shoes and handing out Sacred Heart badges to generations of Notre Dame students.

Born to Irish parents in a Pennsylvania coal mining town, John O’Neill (his name before entering religion) had two club feet and no real access to medical care. Nobody expected him to be able to walk, but John and his four older siblings were coal miner’s kids and they knew how to work—and work and work. His older siblings worked with him until John was finally able to walk in a slow, shuffling gait that earned him plenty of mockery from other children but which eventually took him across the country and most of the way back again.

But the legs that would carry him to Notre Dame were not strong enough for him to work in the mines alongside his father and brothers. Though he worked separating coal from shale from a young age, it was a source of shame and frustration for John (and his father) that he would never be able to be a coal miner. Physically weak and with no education to speak of, there was little hope for young John until he found a cobbler who would teach him the trade. John showed great promise in this craft, but the advent of the Civil War put a stop to any sense of stability in most American lives. The master from whom he was learning his trade enlisted and John (then only about fourteen) set off as a traveling shoemaker, wandering from town to town in Pennsylvania until about 1869 when he began the long walk to Colorado. He stopped in Denver for a while before making his way to California—and nearly all this on foot! That would have been a tall order for any man, but such a feat was even more remarkable for a man with club feet and slow, shuffling steps.

Since the age of fourteen, John had hoped for a vocation to religious life. In California, he attempted to enter a Franciscan community but was denied because of his disability. But God was at work in his wandering and in this rejection. John had made the acquaintance of a talented cobbler and asked the man where he had learned such skill. The answer: “A little school in Indiana called Notre Dame.”

A decade after the Civil War, Notre Dame was no great research university, and while the students did learn science and philosophy, they also learned a number of trades. John was intrigued—not so much by the possibility of learning more about shoemaking but by what he heard about the men who taught at the school. The stories his new friend told of the Brothers of Holy Cross called out to John, who thus set off back east, intent on entering the congregation.

A dozen years after he had wandered from his home in Pennsylvania, John arrived at Notre Dame; it was the summer of 1874. He was twenty-five years old and had finally come home. The Holy Cross Brothers were entirely unperturbed by his disability and John soon entered the congregation, taking the name Columba.

Upon making his vows, Br. Columba made an optional fourth vow to devote himself to the missions, “to go anywhere in the world the Superior General pleases to send me.” He offered immediately to go to India or to the leper colonies of Hawaii; he was sent instead to Lafayette, Indiana, there to serve at an orphan asylum for nine years. Even this had some element of heroism to it, though it was no arduous journey to foreign lands. But Br. Columba had not been called to a life of impressive mission work and before long, he was told to return to Notre Dame, where, rather than mourning his lost opportunity for glory, he embraced the mundane work of mending shoes.

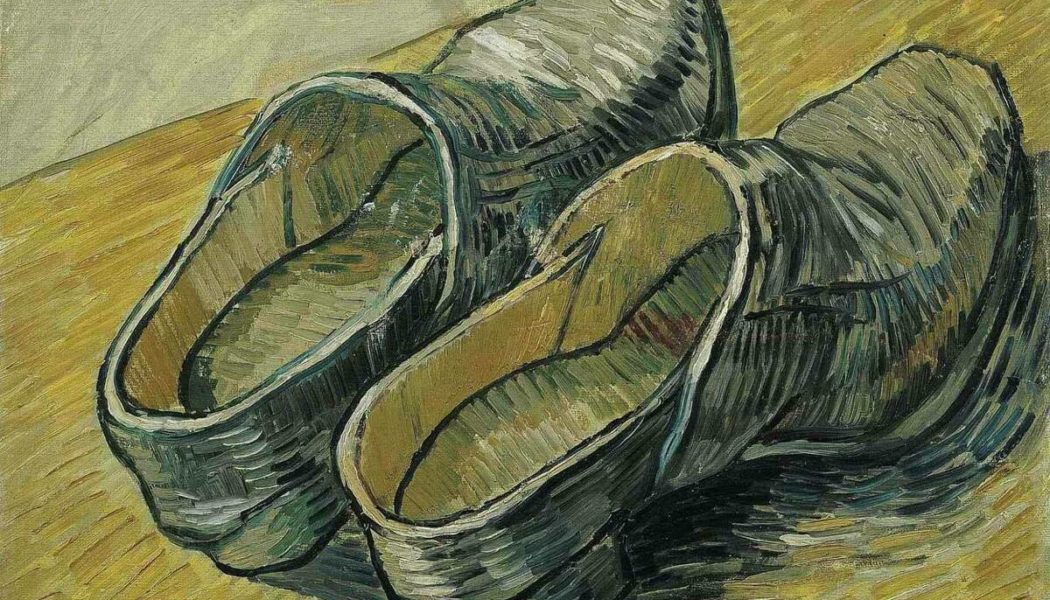

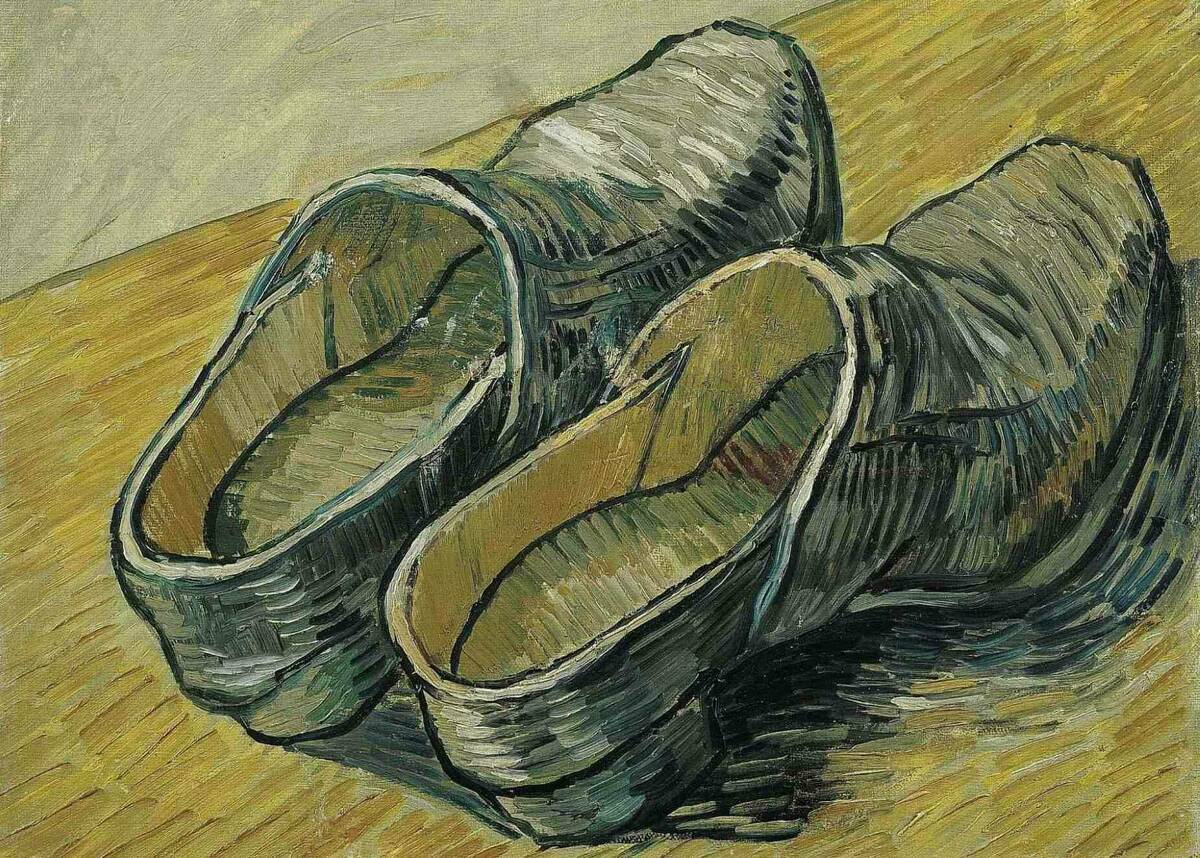

That is what he did for nearly forty years (with two years off to nurse Fr. Sorin as he died). From 1885 on, Br. Columba could generally be found in his shoe shop on South Quad, with a vigil lamp burning before a statue of the Sacred Heart as he worked and prayed—and quietly changed the world. So strong was his devotion to the Sacred Heart that he wanted to share it and so began crafting Sacred Heart badges to hand out to those who might also want a reminder of the abundant love of God poured out in Jesus. He offered Immaculate Heart prayer cards as well, and later chaplets of the Blessed Sacrament. But mostly he made and mended shoes.

Though he objected to the expense, Br. Columba was sent to Chicago for foot surgery by a renowned surgeon; when he had recovered, his lifelong shuffle had become only the slightest limp, an improvement so marked that he regarded it as a miracle. But he never forgot his experience of being disabled, an experience that may have made it easier for him to look with compassion on those who suffered. They sensed this compassion and sought him out, asking for prayers from the simple cobbler. And then the miracles began.

The first one anybody recalls started right there in the cobbler’s shop at Notre Dame, where a man approached Br. Columba seeking special shoes for his disabled son. Remembering all the years of pain that he had endured, Br. Columba was happy to help, but he suggested also that the man take his son to the doctor who had so thoroughly cured Br. Columba. On hearing that there was no money because of an epileptic daughter who needed very expensive care, Br. Columba offered the suffering man a badge of the Sacred Heart, of the same sort that he had been handing out for years. “Tell your daughter to wear this in honor of the Sacred Heart,” he said simply. When the man returned for his son’s shoes a few weeks later, he had tremendous news: his daughter was cured! Br. Columba refused any credit, as would become his habit. “It wasn’t me,” he insisted. “It was the Sacred Heart!”

But the Sacred Heart was working overtime through Br. Columba’s intercession. There were moments of prophecy, so simply uttered that the recipients often did not even notice at the time. There were cures and conversions, addictions overcome, and sanity restored. And after twenty-five years of simple service, Br. Columba accepted it all as a gift from the Sacred Heart. When people wrote to him asking for prayers, he wrote back with confidence (and abysmal grammar). He received dozens of letters each day and wrote to his friends of the many cures effected through his prayers, with no attempt at false humility. “I have a girl on crutches in Detroit,” he wrote. “I told [her] to send the crutches. Don’t laugh.”

“Don’t laugh” was a common refrain in his letters, expressing his own astonishment at the many cures he witnessed. So striking were they that he felt sure that those who had not witnessed them would laugh to hear such claims. Still, he averred, they had happened. All by the power of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Each time he wrote of a cure, Br. Columba described it with simple faith. “The doctors could not understand it,” he wrote once. “If they said their prayers they would.”

Though he lived at a time when Catholics and Protestants were far more divided than they are today, Br. Columba never refused to intercede for a non-Catholic. Indeed, he asserted that Protestants—Black Protestants in particular—were even more likely to be healed than Catholics because of their deep faith. “Protestants nearly all get it,” he wrote (meaning the miracle they sought). And while he told Catholics to pray, “Sacred Heart of Jesus, cure me,” he did not require such a formula from those who were uncomfortable with it. Protestants were told to pray how they liked; in that way, Br. Columba introduced the devotion to the Sacred Heart to those who would never otherwise have encountered it. But he always respected their religious traditions, trusting that God was the one who would show them the truth of the faith. “I won’t say anything about conversion,” he wrote of his plan to visit a Protestant church. “I teach them devotion to the Sacred Heart and tell of the cures. I let the Sacred Heart do the rest.”

Br. Columba was always a man of obedience, so his miraculous intercession had to fit in the margins of the duties assigned to him by his superiors. Generally speaking, that meant making shoes. But as he became better known, they often sent him visiting, making his way through the countryside and eventually throughout the Midwest to visit one person or another who was in need of prayer—but only ever in obedience to his superiors, and always with the self-effacing humility and simplicity for which he was so well-known.

It seems astonishing that such a thing could avoid going to his head, but Br. Columba remained humble, ever the simple miner’s child who was amazed by the good that God was able to do through such a one as he. Even when a local Protestant minister wrote a glowing article detailing the many healings accomplished through Br. Columba’s prayers—some 1,300 at the writing of that 1918 article—the cobbler insisted that it was all God’s power and that he did not know why his prayers had any particular effect. Nor did he know why some were cured and others were not, though he was certain that it was all because God was working to save people’s souls: “It seems as if the Lord cannot make saints out of some people unless He knocks the props from under them.” Even sickness and unanswered prayers were a sign of God’s love in the eyes of the holy cobbler of Notre Dame.

It is impossible to avoid a comparison to St. Andre Bessette, the miracle-working doorkeeper of Montreal who was also a Holy Cross Brother. But while both were unlearned men through whose prayers countless miracles were effected, the similarities extend only to the shape of their lives, not to their characters. Though saintly, Br. Andre was grumpy, constantly struggling with the desire to dismiss the thousands of people who disrupted his life. Br. Columba, on the other hand, seems by all accounts to have been astonishingly cheerful, always happy to pause in his work in order to listen to the struggles of a new visitor or to respond to letters late into the evening.

It was nearly forty years before Br. Columba would consent to have secretaries take dictation for him. Though the president of the University had tried to assign students to the task when the miracles first began (mortified as he was that Br. Columba’s misspellings and bad grammar were being sent out on University letterhead), Br. Columba was embarrassed at the idea, certain that he would become tongue-tied if asked to do something so grand as to dictate a letter. As he neared the end, though, he did not have the energy to write his own letters and the secretaries were finally sent.

Br. Columba had never fully recovered from his 1920 bout with the Spanish Flu (contracted when he insisted on serving those who were sick despite his advanced age). His breathing worsened in the spring of 1923 and he spent his last few months in bed, struggling to breathe but never ceasing his prayers to the Sacred Heart. Before he died, he summarized his life with astonishing humility: “There was an old shoemaker at Notre Dame, and he had a devotion to the Sacred Heart, and there seem to have been some cures.”

Br. Columba O’Neill died peacefully at 75, a faithful religious who thought of himself as nothing more than an old shoemaker. In some ways he was right. But the people around him recognized far more in him. His eulogy (delivered by Fr. O’Donnell, the Holy Cross provincial) marveled at the dichotomy:

With all his wisdom and his years, he was but a simple, good child . . . His no distinction of birth, or wealth, or education, as the world sees it. He wrote nothing, he invented nothing, he contributed nothing to the progress of mankind. He was a shoemaker by day, and sometimes a nurse by night. Yet his name was known to thousands, many of whom came in the course of a year to visit him; the notice of his death is carried by the public press throughout the land, and the religious family of which he was a member unites to give him all the honor within our power to bestow.

Fr. O’Donnell described him as “a miraculous man cut from an apparently un-miraculous cloth” and described his work in the shoe shop thus: “There he remained and worked till in the course of time and the Providence of God the cobbler’s shop itself became a shrine. The humble shoemaker had somehow learned to mend immortal souls.”

Ours is a culture that values strength over simplicity, genius over faithfulness, and success overall. To us, Servant of God Columba O’Neill stands as a witness that holiness lies not in great accomplishments but in the willingness to serve humbly and to fix our hearts on Jesus. Through his intercession, may we embrace our weaknesses and rest content in the gifts God has (and has not) given us.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity