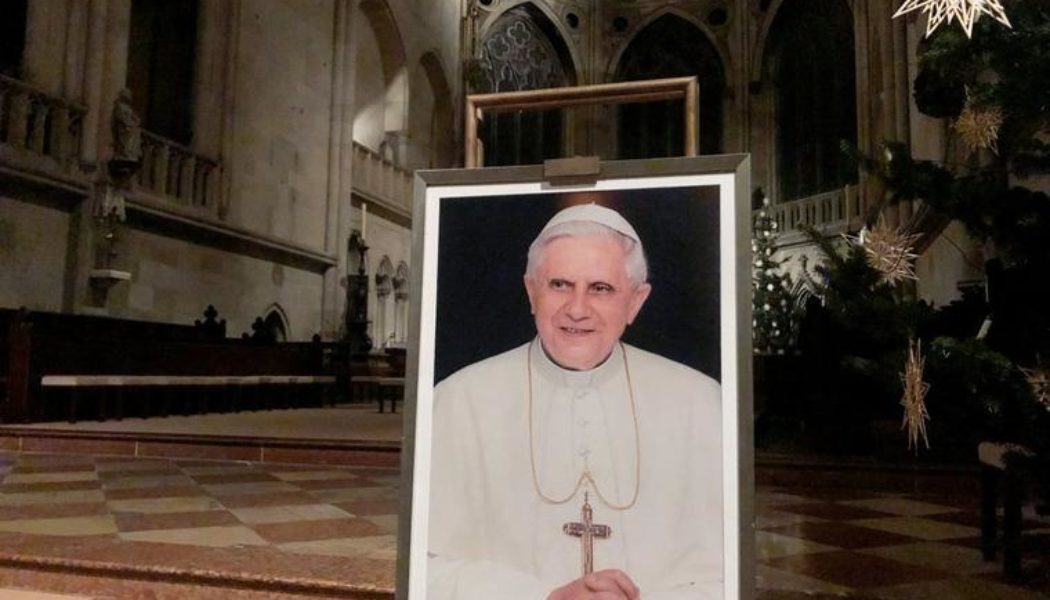

COMMENTARY: The last of the monumental figures of 20th-century Catholicism bears no resemblance to the caricature created by his theological and cultural foes.

The Joseph Ratzinger I knew for 35 years — first as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), later as Pope Benedict XVI and then pope emeritus — was a brilliant, holy man who bore no resemblance to the caricature that was first created by his theological enemies and then set in media concrete.

The cartoon Ratzinger was a grim, relentless ecclesiastical inquisitor/enforcer, “God’s Rottweiler.” The man I knew was a consummate gentleman with a gentle soul, a shy man who nonetheless had a robust sense of humor, and a Mozart lover who was fundamentally a happy person, not a sour crank.

The cartoon Ratzinger was incapable of understanding or appreciating modern thought. The Ratzinger I knew was arguably the most learned man in the world, with an encyclopedic knowledge of Christian theology (Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant), philosophy (ancient, medieval and modern), biblical studies (Jewish and Christian), and political theory (classic and contemporary). His mind was luminous and orderly, and when asked a question, he would answer in complete paragraphs — in his third or fourth language.

The cartoon Ratzinger was a political reactionary, discombobulated by the 1968 student protests in Germany and longing for a restoration of the monarchic past; his more vicious enemies hinted at Nazi sympathies (hence the nasty sobriquet Panzerkardinal). The Ratzinger I knew was the German who, on a state visit to the United Kingdom in 2010, thanked the people of the U.K. for winning the Battle of Britain — a Bavarian Christian Democrat (which would put him slightly left of center in U.S. political terms) whose disdain for Marxism was both theoretical (it made no sense philosophically) and practical (it never worked and was inherently totalitarian and murderous). The cartoon Ratzinger was the enemy of the Second Vatican Council. The Ratzinger I knew was, in his mid-30s, one of the three most influential and productive theologians at Vatican II — the man who, as CDF prefect, worked in harness with John Paul II to give the Council an authoritative interpretation, which he deepened during his own papacy.

The cartoon Ratzinger was a liturgical troglodyte determined to turn back the clock of liturgical reform. The Ratzinger I knew was deeply influenced, spiritually and theologically, by the 20th-century liturgical movement. Ratzinger became a far more generous pope in his embrace of legitimate liturgical pluralism than his papal successor, because Benedict XVI believed that, out of such a vital pluralism, the noble goals of the liturgical movement that formed him would eventually be realized in a Church empowered by reverent worship for mission and service.

The cartoon Ratzinger was yesterday’s story, an intellectual throwback whose books would soon gather dust and crumble away, leaving no imprint on the Church or on world culture. The Ratzinger I knew was one of the few contemporary authors who could be certain that his books would be read centuries from now. I also suspect that some of the homilies of this greatest papal preacher since Pope St. Gregory the Great will eventually find their way into the Church’s official daily prayer, the Liturgy of the Hours.

The cartoon Ratzinger craved power. The Ratzinger I knew tried three times to resign his post in the Curia, had zero desire to be pope, told fellow Churchmen in 2005 that he was “not a man of governo [governance],” and only accepted his election to the papacy in obedience to what he regarded as God’s will, manifest through the overwhelming vote of his brother cardinals.

The cartoon Ratzinger was indifferent to the crisis of clerical sexual abuse. The Ratzinger I knew did as much as anyone, as the cardinal-prefect of CDF and then as pope, to cleanse the Church of what he brutally and accurately described as “filth.”

The key to the true Joseph Ratzinger, and to his greatness, was the depth of his love for the Lord Jesus — a love refined by an extraordinary theological and exegetical intelligence, manifest in his trilogy, Jesus of Nazareth, which he regarded as the capstone of his lifelong scholarly project. In those books, more than six decades of learning were distilled into an account that he hoped would help others to come and love Jesus as he did, for as he insisted in so many variations on one great theme, “friendship with Jesus Christ” was the beginning, the sine qua non, of the Christian life. And fostering that friendship was the whole purpose of the Church.

The last of the monumental figures of 20th-century Catholicism has gone home to God, who will not fail to reward his good servant.