As a systems engineer, he knew how to organize a project, and through the years he assembled an increasingly sophisticated strategy for finding the hard drive. He met with potential investors, and eventually made arrangements with two European businessmen who agreed to support a recovery operation. Howells would get only about a third of the proceeds. He had hoped for a much higher sum; the money was his, after all. He recalls being told, “James, that’s not how it works.” He also consulted with companies that could perform targeted landfill removals. He became increasingly convinced that this was a realistic path. (“They probably move more dirt in one season of ‘Gold Rush: Alaska’ than would be required for this operation,” he told me.) This past January, he obtained a letter from Ontrack testifying that the drive was likely recoverable, and, after the Newport dump manager who’d explained to him the architecture of the landfill retired, Howells enlisted him as an expert.

Earlier this year, as the value of each bitcoin passed thirty-five thousand dollars, and Howells’s holdings exceeded two hundred and eighty million dollars, he made a public offer to give Newport a twenty-five-per-cent cut of the proceeds, which could be earmarked for a COVID-19 relief fund. The city did not accept his offer. “The attitude of the council does not compute, it just does not make sense,” Howells complained to the Guardian. Across the Internet, commenters generally did not take a sympathetic view of Howells’s situation. “Your loss fool,” a poster on the Web site WalesOnline declared. “This is the ultimate definition of a ‘Loser,’ ” another wrote, adding, “Wondering how this guy even survived into adulthood.”

For Howells, it was a particularly cruel twist that he could not get a serious meeting with Newport officials despite having become arguably the city’s most famous resident. He had thought that he was striking a blow for the little guy by mining bitcoin; now it was clear that, in Newport at least, little guys still had no power. “It’s my own local team who are screwing me over!” he told me. “It’s not bankers, it’s not somebody from a far distance—it’s the people I’ve grown up with and lived with.”

This past May, Howells finally was granted a Zoom meeting with two city officials, one of whom was responsible for Newport’s waste and sanitation services. She listened politely to his proposal to recover the bitcoin, at no cost to the city, but was not persuaded. As he recalls it, she informed him, “You know, Mr. Howells, there is absolutely zero appetite for this project to go ahead within Newport City Council.” When the meeting ended, she said that she would call him if the situation changed. Months of silence followed. (A spokesperson for the city council told me that the official permit for the site does not allow “excavation work.”)

Earlier this fall, I went to see Howells in Newport. We had been talking and texting for nearly a year, mostly on the messaging app Telegram. He had been by turns evasive and defensive, often coming across as an unyielding cyber libertarian. Tech shaped his world view. At one point, I asked him what he thought about the still novel COVID-19 vaccines. He replied, “Something I’ve learnt from IT world . . . don’t ever get the first version.” This past January, when online brokerage companies restricted trading in GameStop stock in order to limit its price rise, Howells wrote to me, “It shows once and for all, in plain view of everyone watching, that the game (life) is completely and utterly rigged against the little guy.” While we affably fenced, the value of a bitcoin rose to sixty-three thousand dollars in April, then slumped to thirty thousand dollars in July, then rose again.

On October 21st, the day I arrived in Newport, the value of a bitcoin had just hit a new peak: nearly sixty-seven thousand dollars. Howells met me by the train station, wearing jeans and a crisp sweatshirt from Lonsdale. He drives a twenty-year-old BMW convertible that he bought before his bitcoin days. He is small and fit, with a skin-fade haircut and a light-brown half beard. The over-all effect was of concision and capability.

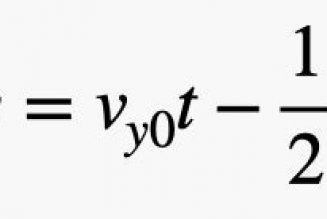

Moments after we sat down in a coffee shop, he pulled out his phone and showed me an app that he uses to track his holdings. Under the rubric “Unspent Coins” was the current value of his bitcoin: $533,963,174. The previous day, he noted, he’d made twenty million dollars. We had Welsh pancakes, and he paid with cash. He explained, “Using credit cards is kind of enabling the opposition, if you see what I mean.”

We next went on a tour of Newport, and he told me about the city’s history of finding lost objects, a topic on which he was very well informed. As we drove across the River Usk, he mentioned that, in 2002, while the city was building a new arts center along its banks, workers had dug up a fifteenth-century Iberian sailing ship. The next day, we visited the local antiquities museum, where he showed me a cooking pot, likely belonging to a Roman soldier, that had been buried in a nearby field. From the shattered remains trickled a trail of coins. Howells compared them to his buried hard drive, then corrected himself: the coins were not like bitcoin at all. Sometimes, he explained, messengers and go-betweens had clipped off a bit of precious metal to repay themselves for the trouble of handling transactions. “People stole from the coins,” he said. The percentage of silver in Roman coins kept declining, setting off runaway inflation. “It’s similar to what the central banks are doing today,” he said. The widespread use of bitcoin, he assured me, would prevent a similar economic collapse.

We went to the dump. It was a bucolic site between an estuary and docks where, many years ago, ships had been loaded with Welsh coal. Derricks stood idle. To get to the landfill, we had to drive past some city offices—“the enemy,” Howells joked. Newport felt rickety: faded signs on small businesses, empty land where factories had once stood. As he drove, Howells mused on why the local officials had refused to allow him to dig up his hoard. He theorized that the dump had not been following environmental regulations, and that unearthing a section of landfill could embarrass the city and make it vulnerable to lawsuits. “Who knows how many dirty baby nappies are buried out there?” he asked.

He drove to the area where he had estimated that his hard drive would likely be. We passed through an open gate and stopped in a paved lot. This large, empty space looked like it was destined for some sort of industrial development by the city, but Howells wanted it to serve first as the command headquarters for his excavation project. We got out. “This plot of land is called B-21,” he said—a propitious number. “How many bitcoins exist? Twenty-one million!”

The sun was shining, an unusual occurrence in Wales in the fall. He pointed at an incline about a hundred feet away: at the top was a tufted hill with gauges inserted in it, to measure gas release. “The total area we want to dig is two hundred and fifty metres by two hundred and fifty metres by fifteen metres deep,” he told me, with excitement. “It’s forty thousand tons of waste. It’s not impossible, is it?”

After our visit to the dump, Howells invited me to his house, so that I could see a PowerPoint presentation he’d delivered, on Zoom, to the Newport officials. His project, he told me, was budgeted at five million pounds, but “there is scope for additional funding.” He calculated that a crew of twenty-five could complete the job in nine months to a year. As he spoke, his dog, Ruby, ran back and forth at our feet. Before he showed me the slides, we went down the street to buy beer and crisps at the nearest convenience store. He had equipped the cashier to accept bitcoin a few years ago, but it had not proved a success. “No one used it but me,” Howells said, shrugging. He gave the proprietor two pounds, and a pound that he owed from an earlier visit.

We returned to his house. On a wall of the living room, above his computer, was a gold-and-black Bitcoin clock. Its hands were stopped. Howells checked his holdings. He was down twenty-two million dollars that day, but he was unperturbed. “I expected this,” he said. “Whenever it shoots up so fast, you always have to expect it to come down a little. In fact, I expect it to come down a lot more.”

He loaded the PowerPoint presentation and pulled up a slide titled “Consortium Members.” An avatar of Howells was at the center, with a pickaxe and a bag of gold. Another slide depicted a flowchart of the process by which his hard drive would be returned to him: dump trucks would carry items from the pit to a hopper, which would feed them onto a conveyor belt, from which “the material would pass under a large 3-D object detection system to identify all hard drive objects for manual retrieval.” The object detector was an X-ray machine outfitted with artificial-intelligence software. “It can spot a gun inside a truck!” Howells told me. All detritus would be loaded onto forty-ton trucks and then, according to Newport’s preference, would be reburied, incinerated, or sent to China.

I said that surely there was an easier way. The whole point of bitcoin was that it was immaterial. It was the eight thousand bitcoins that he was after, and they were the product of a computer algorithm. It was a matter of public record that someone owned them. Why not just run the system backward to the day that Howells mined his coins, and let him re-mine them?

Howells recoiled. My proposal reminded him, he said, of the worst moment in cryptocurrency history. In 2016, the managers of a competing cryptocurrency platform, Ethereum, agreed to restore the equivalent of sixty million dollars to one of the currency’s holders, after the money was stolen through a vulnerability in the system’s code. Howells had publicly disagreed with this decision at the time—he has been very active on crypto social-media sites—and when Ethereum’s holders split into two camps he sided with those who refused to acknowledge the rollback. Howells told me, with considerable passion, “Just for the record, if somebody came along and said, ‘We can get your five hundred million by doing it this way,’ I’d say, ‘No, thank you.’ Because if they can do it that way for my coins, then they can do it that way for anyone’s coins. And then, if the government asked them to seize someone’s coins, guess what? They could do that as well.”

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity

![This guy threw out a hard drive containing $384 million of Bitcoin. Now he’s fighting to dig up the landfill [language warning]…](https://salvationprosperity.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/this-guy-threw-out-a-hard-drive-containing-384-million-of-bitcoin-now-hes-fighting-to-dig-up-the-landfill-language-warning-1050x600.jpg)