The very first line and the very last line are the most important parts of the Gospel for the Fifth Sunday of Lent Year C as Jesus teaches the way forward from sin of all kinds, but particularly from sexual sin.

The shame and pain of sexual sin causes anger, strife, and despair, but Jesus is here to lead sin’s slaves, like a new Moses, to a place of freedom.

But first, it is worth noting that even the history of the Gospel’s text might be a history of shame.

St. Jerome notes that the story about the woman caught in adultery is missing from many ancient copies of the Gospel text. While modern scholars often say it was added in to the Gospel from a different source, St. Augustine suggests that angry men took it out.

Why? “Some of slight faith, or rather, some hostile to true faith, fearing, as I believe, that a liberty to sin with impunity is granted their wives, remove from their Scriptural texts the account of our Lord’s pardon of the adulteress, as though when he said ‘From now on, sin no more’ he granted permission to sin.”

Whatever the reason the text was missing, Augustine’s suggestion explains one reason the Pharisees used this woman’s case as a trap.

“Teacher, this woman was caught in the very act of committing adultery,” the Pharisees say. “Now in the law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. So what do you say?”

John tells us that “They said this to test him, so that they could have some charge to bring against him.”

Surely Jesus could not forgive an adulteress woman, they thought. Men would not stand for that. And on the other hand, if Jesus ordered the stoning of the woman, he would show that he never really meant all those messages of mercy he had been embarrassing them with, like the Prodigal Son story.

They thought they were putting him in a no-win situation, but as usual he uses the situation to put them in a no-win situation by saying, “Let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.”

He points out that these righteous executioners were sinners too — perhaps even guilty of sexual sin. Jesus tells them, as St. Augustine put it, “If you think I ought to condemn sins, I shall begin with you.”

Jesus does more than show up the Pharisees, though. Jesus models what our behavior toward sexual sinners should be.

“Jesus bent down and began to write on the ground with his finger,” says John, who with that detail suggests that he was an eyewitness to the scene. What did he write? No one knows, and while many suggestions have been made, one thing is clear: That he wrote on the ground is the point, not what he wrote on the ground.

He is modeling what our behavior should be when faced with a sinner. His pause to write in the sand suggests that we should recollect ourselves before we react, and set ourselves apart from both the accuser and the accused.

What should we think about in that pause? The Golden Rule: “Do to others whatever you would have them do to you.” If any of us were caught in a shameful sin, we would want pity and understanding. So this is what we should give to others.

The accusers recognize this. St. John tells us, “And in response, they went away one by one, beginning with the elders.”

What Jesus says to the adulterous woman should be a balm to those caught in a trap of sexual sin.

“Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” he asks.

She replies, “No one, sir.”

Then Jesus delivers this Gospel’s pivotal last words: “Neither do I condemn you. Go, and from now on do not sin any more.”

Look at what Jesus does for her. Sexual sin is isolating and humiliating. The devil starts out tempting the sinner to something enticing and exciting and ends by telling the sinner that he is worthless and disgusting. Sexual sins are also uniquely connected to past wounds that burn in the memory, leaving a lingering despair.

This is why so many young people who are caught up in sexting become suicidal when their images become public. They feel they have redefined themselves and can never come back. Other sexual sinners experience something similar. The research of Jay Stringer in his book Unwanted: How Sexual Brokenness Reveals Our Way to Healing shows that pornography addicts are often attracted to the very images that remind them of degrading events from their pasts.

Sexual sinners are saying with their actions: “I feel like damaged goods and I no longer deserve better, so I will ape love’s actions in ugly ways that fit who I am.”

What a tremendous relief it must have been for this woman to look into the loving eyes of her savior and hear his words, “Where are they? Has no one condemned you?” He is saying: “Where are the high and mighty who treated you like a piece of trash? They fled at the slightest suggestion that their own sins might be revealed. They are no better than you.”

And then Jesus says those words that are the master key to the whole incident: “Neither do I condemn you. Go, and sin no more.”

The vote of confidence from Jesus Christ must have been overwhelming. He says in effect: “You see who I am, and the authority I have, my ability to strike fear into the righteous people who accuse you. And I am telling you that I trust you more than I trust them. I trust that you can go from here changed. I trust that you do not have to return to this ugliness and impurity. I trust that your human nature, at its core, is good, and that you don’t have to keep rooting around in the mud of your past. I have forgiven you, and my forgiveness restores innocence. Go forward on my authority and be who you are. Sin no more.”

St. Augustine says that because of her contact with Jesus she is “cured by the divine physician.”

And that’s where the very first line of Sunday’s Gospel, I think, becomes important.

“Jesus went to the Mount of Olives,” the Gospel begins, then “early in the morning he arrived again in the temple area and all the people started coming to him.”

Jesus Christ is the Second Person of the Trinity. He is one with the Father and through him all things were made. He exists outside of time in absolute unity with the Trinity. For God the Mount of Olives is filled with all the associations of its past, present, and future. And the Garden of Gethsemane at the foot of the Mount of Olives is the place where Jesus takes onto himself the sins of every sinner — yours, mine, and the adulterous woman’s.

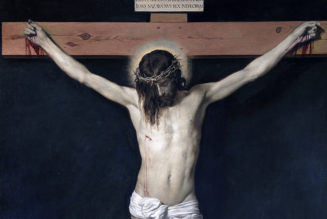

The Law says the woman should die for her adultery. Jesus knows the Law comes from God, and, just as he said, he, the “one without sin,” will be the first to see that sentence carried out — because he will die in her place for her adultery, suffering her torment, starting on the Mount of Olives, where he will sweat blood, as if his body were being pummeled by stones.

Weeks later, when she saw or heard about his sacrifice on the cross, she must have experienced something like what St. Paul describes in Sunday’s Second Reading: “For his sake I have accepted the loss of all things and I consider them so much rubbish, that I may gain Christ and be found in him, not having any righteousness of my own based on the law but that which comes through faith in Christ.”

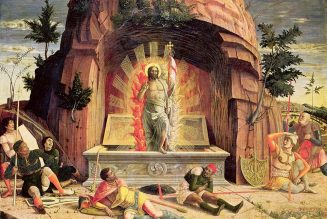

What was redemption like for the adulterous woman? The earlier readings give a remarkable picture of it.

The First Reading from Isaiah describes a New Exodus, one like the Hebrew people breaking free of slavery in Egypt. Their past slavers pursued them, but the Lord, “snuffed them out” leaving them “quenched like a wick” in the Red Sea. His advice to sexual sinners, and all of us, is: “Remember not the events of the past, the things of long ago consider not; see, I am doing something new!”

Sunday’s Psalm describes the return from exile in Babylon the same way: “Our mouth was filled with laughter, and our tongue with rejoicing,” it says. “Like the torrents in the southern desert. Those that sow in tears shall reap rejoicing.”

Pray the First Reading and the Psalm. They describe what freedom and forgiveness after the sacrament of confession looks like, when the same Lord who forgave the woman caught in adultery forgives us, unleashing our baptismal grace like a flood. The prayer of Stephen Langton, a 12th century Archbishop of Canterbury, captures it:

“Holy Spirit: Wash what is unclean.

Water what is parched.

Heal what is diseased.

Bend what is rigid.

Warm what is cold.

Straighten what is crooked.”

But freedom from sin, including sexual sin, has to be chosen each day.

For the Israelites, the Exodus from Egypt and the return from Babylon were beginnings in their journey, not their journey’s end. It’s the same with for those forgiven in Christ.

St. Paul describes the road ahead this way: “Forgetting what lies behind but straining forward to what lies ahead, I continue my pursuit toward the goal, the prize of God’s upward calling, in Christ Jesus.”

God gives his people a new identity; a new direction; a new life to replace the painful memories of the past, pressing on to the higher calling of our Lord.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity