St. Bartholomew is one of the 12 Apostles, but one about whom relatively less is known. Certain Apostles immediately stand out: Peter, James the Greater and John come to mind. Certain Apostles are known only by name — think Simon or Jude Thaddeus (loss of whose memory is further compounded, as the St. Jude Novena Prayer used to put it, by “the name of the traitor [who] has caused you to be forgotten by many.”

But then there’s a middle group, occasionally mentioned but not very prominent. Think Matthew, who’s called from his tax collector’s table to follow Jesus. Think Philip, who apart from some questions he poses to Jesus gets one of his few starring roles in the Gospels by finding Bartholomew under a fig tree and leading him to Jesus.

Two comments about his coming to Jesus. First, the Bible shows us the importance of family and friends in our relationship to God. Andrew brings his brother, Peter, to Christ (John 1:40-42). Philip brings Nathanael to Jesus (John 1:45-46). What was their relationship — friend or family? Probably the former, since biblical tradition tends to mention the latter. The important thing is that somebody else helped a friend or relative to come to Jesus. Are there any friends or relatives I should help to come (or come back) to Jesus?

Second, note I wrote “Philip brings Nathanael to Jesus.” Isn’t this essay about St. Bartholomew? Well, yes and yes. Most of the Biblical tradition has identified Bartholomew and Nathanael. There were some dissident voices, e.g., who claim that John’s Gospel sometimes focuses on people — like Nicodemus — that the other Gospels do not mention. But, as I said, there are solid arguments in the tradition for considering Bartholomew and Nathanael the same, and I accept them.

“Bartholomew” in fact, may not even be a proper name (which is probably why the Bible — which knows that God calls us by name (see Isaiah 43:1) — prefers the proper name “Nathanael.” Etymologically, “Bartholomew” means “son (bar) of Tolmai.” The Biblical world was not one of isolated individuals: one’s identity was associated with one’s family, clan and tribe. Consider the two genealogies of Jesus (Matthew 1:1-17, Luke 3:23-38) — “and X was the father of Y, Y was the father of Z” — to appreciate the role roots played in ancient Israel.

Philip finds Nathanael sleeping under a fig tree, grabs him by the hand, and leads him to Christ. The manner in which he presents Jesus also points to this relatedness aspect of his world: “We have found the one Moses wrote about in the Law and about whom the prophets wrote — Jesus of Nazareth, son of Joseph” (John 1:45). Philip’s introduction is simultaneously a declaration of faith: Jesus is the one to whom the two most important sources of Jewish religion — the Law and the Prophets — lead. Had Philip been at the Transfiguration, he would have known why Moses and Elijah speak to Jesus. And Philip tells the son of Tolmai about the son of Joseph.

Nathanael is a bit blasé at first: seizing on Jesus’ hometown, his is a bit of a put down: “Can anything good come from Nazareth?” (John 1:46). He’s Galilean himself, from Cana. Nazareth was a poor and tiny town in Galilee. Bethlehem at least had the Davidic pedigree, but the Perth Amboy of Galilee? (I love my hometown but, based on experience, some places — in the words of Rodney Dangerfield — unfairly “don’t get no respect.”) But Nathanael goes.

And Jesus greets him with respect but also a bit of tongue-in-cheek: “Here is an Israelite in whom there is no deceit” (John 1:47). Nathanael told it like he thought about Nazareth, and Jesus recognize his candor.

Bartholomew is caught off guard: “I saw you under the fig tree before Philip called you” (John 1:48b), says Jesus. It’s a clear allusion to the God who “before you were born, I knew you” (Jeremiah 1:5). That’s why Bartholomew, like Philip, makes his own declaration of faith: “Rabbi, you are the Son of God; you are the King of Israel” (John 1:49).

Jesus’ response is salvific and eschatological: alluding to Jacob’s Ladder (Gen 28:10-17), I follow the Polish writer, Roman Brandstaetter, who sees in Jacob’s Ladder the Incarnation Son of God, Jesus Christ, the “Ladder’ who connects heaven and earth, with whom Nathanael just began the adventure of a lifetime.

After starting his Apostolic vocation with Jesus, we don’t hear much else about Nathanael, other than being listed among the Apostles, in the New Testament. He’s a witness to the Apostles’ miraculous catch of fish on the Sea of Galilee (Tiberias) following the Resurrection: see John 21:1.

Tradition says that Bartholomew preached in the East, often spoken of as “India.” As the Catholic Encyclopedia notes, “India” at that time was a pretty broad and somewhat ambiguous concept: almost 1,500 years later, even Christopher Columbus thought the Caribbean was the “Indies.”

Apart from his calling, many people probably remember Bartholomew/Nathanael for the method of his martyrdom: he was “flayed,” i.e., skinned alive. This was a particularly brutal, humiliating and excruciating torture that we know reached all the way back to the Assyrians, who were not exactly the kindest and gentlest invaders of Antiquity. Michelangelo captures it in his “Last Judgment” (with some believing Bartholomew’s skin being how the artist got himself into the picture).

Think of when you sit down to dinner and, in the name of reducing calories, remove the skin from that piece of chicken, turkey or salmon lying on your plate. Now imagine doing the same thing to a living human being. That’s how St. Bartholomew was put to death.

For some reason, the cult of St. Bartholomew took off in late medieval and Renaissance/Baroque Spain. I confess to some surprise, because I’d typically associated that country with St. James and the pilgrimage road to Santiago de Compostela.

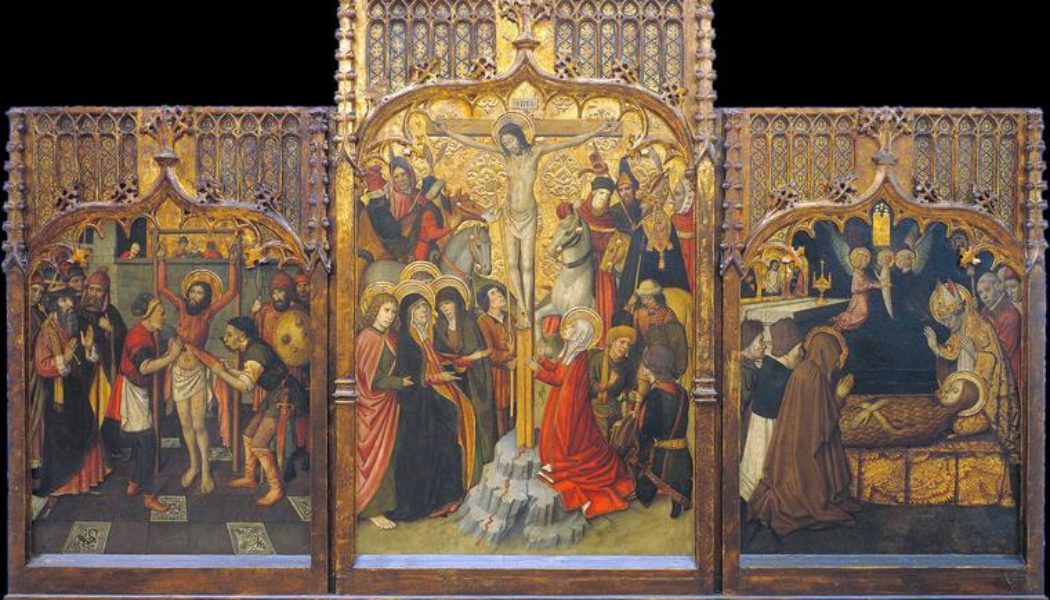

Many art historians consider Jusepe de Ribera’s “Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew” one of the best examples of Spanish art connected with St. Bartholomew. I prefer, however, an earlier work by 15th-century late Gothic Catalan painter Jaume Huguet. His is the altarpiece depicting Calvary with the Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew and the death of St. Mary Magdalene. It dates from around 1480 (a dozen years before Columbus and before the unification of Spain). It is found at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya in Barcelona. (For those interested in other artistic examples of the Iberian cult of St. Bartholomew, also in Barcelona, see here, here and here.)

Huguet’s work is a theologically sophisticated example of late Gothic art. The death of a Christian, be it by martyrdom or any other cause, makes sense only in the light of the death of Christ. Baptism is baptism into his death (Romans 6:3). Bartholomew’s martyrdom is of interest not out of some morbid interest in its particular gruesomeness, but because it was a share in the Paschal Mystery of Christ. Where Christ went, the Christian must follow: “If anyone would come after me, let him … take up his cross daily and follow me” (Luke 9:23). In a few weeks, we’ll hear that line in the Sunday Gospel. Bartholomew concretely shows us what that means. (Note that even in Ribera’s painting, Bartholomew’s body is placed in a cruciform position).

In the altarpiece, Jesus’ Passion and Death is rightly center stage. Interestingly, of the two deaths recorded on the side panels, only one was beneath that Cross: Mary Magdalene, almost certainly the woman in red. (One art historian once commented that it’s almost impossible to put Mary Magdalene in a painting without making her the most physically beautiful woman there). Mary, the most spiritually beautiful and in whose direction Jesus’ head is bent, is supported by St. John. Bartholomew, like the other Apostles, is not to be found, which is why tradition holds that John — having experienced the living martyrdom of Calvary — was exempted the sole Apostle exempted from martyrdom himself.

On the left, St. Bartholomew’s executioners are busily stripping a layer of flesh away from him as spectators look on. One of the executioners is holding a flaying knife in his mouth as he peels off a strip of the Apostle’s skin. His bloodstained sword and boots attest to his diligence. On the right, Mary Magdalene, in an almost Dormition-like scene, expires peacefully on her bed while two angels conduct her small soul heavenwards. Anachronistically, a bishop in full episcopal regalia blesses her as she dies, affirming the importance of spiritual assistance at this most decisive moment of one’s life, a moment that gets its significance from the One dying in the middle of this altarpiece, whose scourged image is depicted opposite Magdalene’s now closed eyes. Let us aspire to die with Jesus in our sights and his Name the last word on our lips.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity