The mosaic of Nativity in the baptistery of the Saint Sebastian cathedral designed by Jesuit Father Marko Ivan Rupnik. Shutterstock

The day that I saw reports that Jesuit Father Marko Ivan Rupnik had serially abused members of a women’s religious community — while serving as their chaplain in the 1990s — I was scheduled to concelebrate Mass at an altar he had designed. During the Mass, I was seeing red. I was so angry that I could barely look at the adornments that he — along with members of the Roman atelier Centro Aletti — had made. My eyes tried feebly to look past the mosaics, to simply cut the tabernacle from my view.

But I couldn’t shake my eyes from the brilliant red side of the altar. The panel depicting the cross, emblazoned with the words Sanguis Christi, drips in my memory as I write these words. Blood of Christ, cleanse us.

Questions remain

Since the recent revelation of his crimes, the Associated Press has reported that Father Rupnik has been convicted of a grave crime that, according to Church law, brings with it the penalty of automatic excommunication: He absolved in the Sacrament of Confession an accomplice in a sin against the Sixth Commandment. And while serious questions remain about the lack of transparency of the Society of Jesus concerning his crimes and the seemingly unusual leniency of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith in the adjudication of his case (infuriatingly, he designed the logo for the 2022 World Meeting of Families after having been censured!), an additional question looms for believers: What do we do with Father Rupnik’s art?

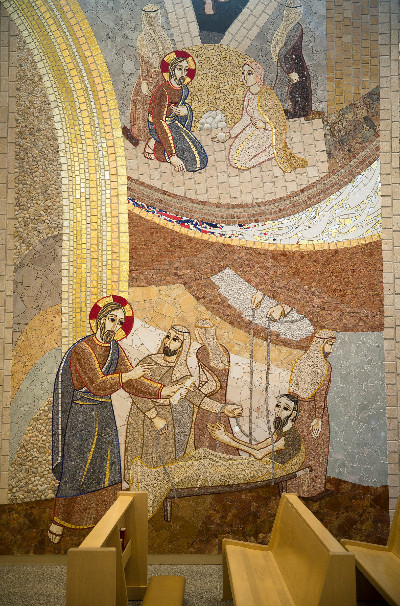

A depiction of the risen Christ appearing to his disciples is seen in a mosaic at the shrine in Lourdes, France. (CNS file photo/Nancy Wiechec)

Father Rupnik is a famous priest artist in Catholic circles, perhaps the most influential priest artist of the 20th century. His works grace the facade of the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary in Lourdes, France, the Redemptoris Mater Chapel in the Apostolic Palace, the St. John Paul II Shrine in Washington, D.C., and churches and chapels throughout the world. His art was not only sacred art, it was ecclesial. Father Rupnik’s work was designed for sacred spaces, to ennoble our acts of worship. His art aims at helping us to communicate with God.

But how could we look past such deeds? My first instinct is to strip it all. Remove every last tile. Hire jackhammers and drills and remove every trace. There’s something biblical about such a notion. In the Old Testament, the sins of an anointed priest demanded the sacrifice of a bull, and the blood of that sacrifice was carried into the tent of meeting and various sacred fixtures were anointed with the blood (cf. Lv 4).

But to strip it all betrays a fundamentally un-Christian notion. The damnatio memoriae is a decidedly pagan practice. Some installations could remove Father’s name and leave the works attributed to the Centro Aletti. But it might be more satisfactory to scar it. What if we removed a panel or two from the larger scenes? There would something fitting about the absence, a public reminder of the wounds caused by sexual abuse and the lies that surround it.

We could leave the art untouched of course, but then detail his biography in every place where his art hangs. We could install signs that explain his crimes and note them in brochures. It’s hard to imagine future studies of Catholic art both ignoring Father Rupnik’s contribution and remaining silent about his past.

The very worst thing is to say nothing at all. We’ve all seen the effect of the unuttered words in our churches these past decades.

The good of art is the art itself

But ultimately, the more I think of it, the more clearly I see that all four of those responses to Father Rupnik’s art flow from a false premise, which is a greater problem.

The good of art is in the work of art itself. If we say anything else, we concede that art is, of itself and in fact, ideological. To deny that the good of art is the work of art itself will result in every creation being simply political speech.

Consider the example of a novel. If I reject a beloved children’s story because the author is deemed by the LGBTQ lobby a “trans-exclusionary radical feminist” — or if i decide to love the work more deeply because I agree with her position — then I’ve fallen into the trap. Art is not a cipher for the good of a particular person. Just as the demeanor of a sleepy priest in no way invalidates the Mass, the work itself is not a measure of the soul of the artist. Art has to be judged by its own standards, not by the moral residue of a work’s creator.

A woman prays during Mass at the St. John Paul II National Shrine in Washington Nov. 28, 2017. (CNS photo/Tyler Orsburn)

Christian art is made in history

Christian art is by its very nature embodied. It is placed in history. That history is usually imperfect and sometimes dramatically unsavory, even in celebrated monuments of Christian art. If we insist on an absolutely pure moral history for all works of sacred art, we give in to the temptation for an artistic Donatism, the ancient heresy that demanded a perfectly pure Church already here on earth, rather than in the new heavens of paradise. Consider the example of Pope Paul III, who designed the Sala Regia (the room where traditionally popes receive heads of state) in the apostolic palace. His name covers the ceiling: Paulus III- Pont Max, Paulus III- Pont Max, Paulus III- Pont Max. But this man had numerous illegitimate children and shamelessly used the papacy to consolidate his family’s power. Could John Paul II or Benedict XVI not have known this? Should Pope Francis wipe the ceilings of the Vatican free from his name thereby purifying them of corruption and sin?

A mosaic illustrating the Gospel story of Jesus’ encounter with the woman caught in adultery is seen at the St. John Paul II National Shrine in Washington Nov. 21. (CNS photo/Tyler Orsburn)

Should we pull down the sacred works of Caravaggio from our churches? Should we destroy the sacred art of Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, known then and now as Il Sodoma? Should we burn the Dominican nuns’ chapel designed by Matisse?

For those who learn his story, the sins of Father Rupnik will change the way we experience his art. How could it not? Today, there must be public consequences for Father Rupnik’s predatory and criminal actions. That begins with, and demands, transparency from the Church about his crimes.

But as for his art, we must recall the purpose of art in a sacred space. Art in our churches renders visible the invisible beauty of the sacred mysteries. Jacques Maritain says this, “In the signs it presents to our eyes something infinitely superior to all our human art is manifested, divine Truth itself, the treasure of light that was purchased for us by the blood of Christ.” If the reality manifested by a work of art is not the beauty of God made known in the sacraments, it does not belong in a church. But if it is, it does, regardless of the artist’s state of soul.

If one believes that the works themselves are worthy to attend the sacred mysteries, then they are. We must, by the grace of God, seek a deeper healing, seek something more than expunging history. In a letter to Raymund of Capua, her spiritual adviser, Catherine of Siena writes: “I beg you dearest Father to pray earnestly that you and I together may drown ourselves in the blood of the humble Lamb. This will make us strong and faithful.” The only way to be cleansed is to be inebriated with the Sanguis Christi. Anything else is politics and show.

Editor’s note: A word of thanks to Father Gabriel Torretta, OP, whose contributions significantly improved this commentary.

Father Patrick Briscoe, OP, is editor of Our Sunday Visitor. Follow him on Twitter @PatrickMaryOP.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity