1918, Sisters and Church Closings

March 21, 2020 by Amy Welborn

A few years ago, I set out to research my grandmother’s early childhood in Philadelphia, looking for clues about what the world was like in the first precarious years of her life. I knew that she was born in October 1917, that she had lived through the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 as a baby, but I was unprepared for the harrowing details I uncovered in my search.

Reading about the fall of 1918 left me grappling with a series of images of the outbreak as it was experienced locally: hushed streets, shut doors, bodies piled up in basements and on porches because the morgues had run out of coffins. Businesses and public

spaces citywide were shuttered, including churches, schools and theaters. In a single day, on Oct. 16, more than 700 people in Philadelphia died from influenza.

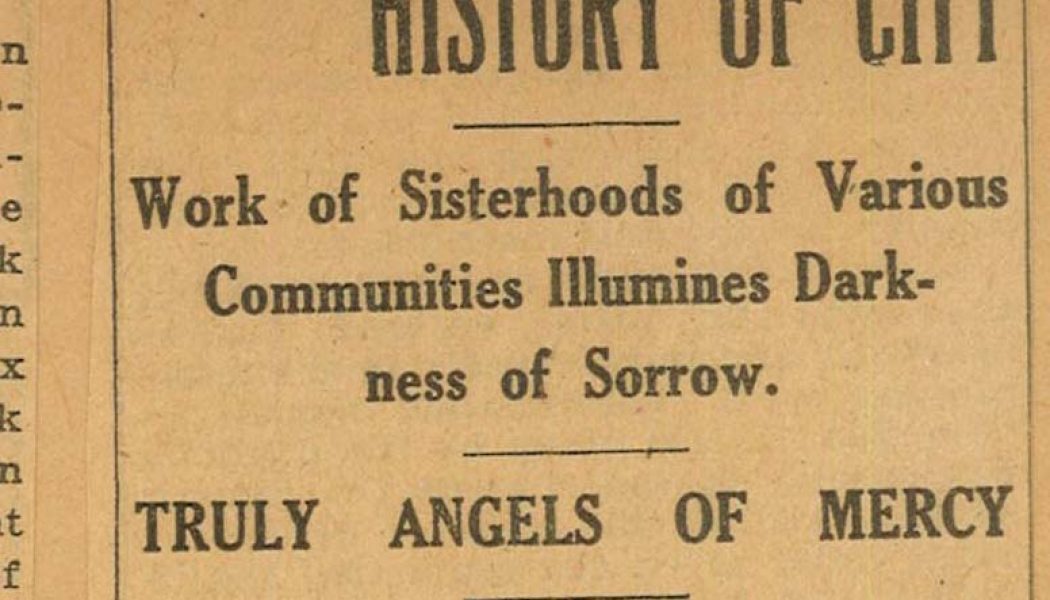

But as I read the first alarming headlines about the coronavirus in January, what came to mind from my family research was one particular document, an oral history published in 1919 by the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia to preserve living memories of the Spanish flu. “Facts unrecorded are quickly lost in the new interests of changing time,” its author began; here, he meant to “gather information for the future.” Within these unassuming pages, I found the story of an extraordinary act of generosity and compassion, carried out at the height of a pandemic. Titled “Work of the Sisters During the Epidemic of Influenza, October 1918,” within this document was evidence of the enormous human capacity for personal sacrifice in the name of public good.

In early October, the Red Cross warned that Philadelphia did not have enough nurses to treat and minister to the sick, whose numbers were growing rapidly. “The nursing forces of the city have been depleted by the war. There was a serious shortage in many of the hospitals before the epidemic broke upon us,” an official cautioned. “Now it is a matter of life and death.” It was in this tense atmosphere that the archbishop of Philadelphia called on nuns in his diocese to leave their convents and take up posts caring for the sick and dying across the city.

You can read the entire document here.

Letter of the Archbishop Authorizing the Opening of Parish Buildings, Halls and Schools for the Use of the Sick, also the Nursing and Relief Work of Uncloistered Sisters. Archbishop’s Residence 1723 Race St. Phila. October 10, 1918.

During the Influenza Epidemic, permission is given to utilize church edifices, particularly halls and parochial schools, as hospitals. Permission is also granted for un- cloistered Sisters to serve as nurses. If need be, the aid of the St. Vincent de Paul Societies should be utilized in each parish. The members of these Societies can help to nurse the patients and also open kit-chens to provide soup and other foods for the sick. These foods could be brought to the doors of the suffering by messengers, particularly by the school-boys. It is left to each pastor to devise the best means to combat the epidemic in his own parish. Priests and nuns are advised to obtain and use masks whilst attendng those attacked by influenza. Very affectionately yours, D. J. Dougherty, Abp. of Phila.

In connection with the closing of churches during the epidemic the following points seem to deserve notice and record :

First – The action of Pastors and Rectors of churches was in accordance with the orders of civil authorities – the State Board of Health, city and local departments of health and public safety – as directed by the letter of his Grace, the Most Revē Archbishop, which follows :

Archbishop’s House 1723 Race St. Philadelphia October 4th, 1918.

Rev. Dear Sir: We hereby direct your attention to the order of the Board of Health, issued on Thursday, October 3d, which prohibits the assemblage of all persons in the churches and schools of Philadelphia until further notice. Yours faithfully in Xto., D. J. Dougherty, Archbishop of Philadelphia .

Second – In many, probably all, the city churches this order was given during the afternoon and evening of Thursday, October 3, when usually there are many Confessions in our churches in view of Communions for the ” First Friday “. The notice to close was generally brought to the church or the rectory by the police then and there on duty. Some of the churches were closed, as reported to the compiler, at 6 o’clock p. m., others at 8 o’clock. Permission was granted in some at least of the churches to allow the people to come to the church on Friday morning, October 4, for Holy Communion. This permission was granted when requested by ‘phone from departments of health or public safety.

Third – While formally and legally closed, the doors of churches were not locked, and attendance at private Masses during the week and on Sundays was not forbidden. Devout and prayerful visits in acknowledgment of the Real Presence, in the churches of the business section of the city were apparently quite as regular and frequent as in normal times.

Fourth – Some of the city churches tried to meet the difficulty by Mass in the open air on Sunday, October 6 and 13. There was no prohibition or public protest against this, so far as the compiler has been able to find; but the practice did not meet with general approval, and, after the second Sunday was discontinued.

Fifth – City churches were closed October 6, 13, 20. The permission to open churches for Sunday, October 27, was followed by unusually large crowds for Confessions on Saturday evening, October 26. The list of the dead in the announcements at Masses on October 27 seemed almost interminable; in some churches more than one hundred names. Outside the city the date for ” reopening ” the churches varied according to different views taken by local boards, and different interpretations given to the action of the State Board of Health in ” lifting the ban “. Some country churches followed the order of city churches and assumed the right to open October 27; others in the same townships, and under the same local boards, did not reopen until November third.