It would be hard to find a place in the world more destitute than Malakal, South Sudan.

The surrounding region defies preconceptions of what the interior of Africa looks like. Watered by the Nile, this is a lush environment which has drawn an eclectic mix of visitors in its history.

In 1898, the nearby settlement of Fashoda (now called Kodok, just upriver from Malakal) was the site of a famous standoff between Lord Kitchener’s British forces and a plucky detachment of French troops under Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand, who had embarked on an epic 14-month trek from West Africa to steal a march on the old enemy who were in the process of conquering all Sudan.

It is strange to think that a dispute over this wilderness once came close to starting a great European war.

Tumult

Malakal’s more recent history is more tragic than strange, as evidenced by the renewed violence before Christmas in the Upper Nile state in which it is situated: violence which has left thousands displaced.

Malakal was one of the largest cities in the unified Sudan, with a large population centre served by an important and busy regional airport.

Heavy fighting between opposition and government forces since the outbreak of the South Sudanese civil war in 2013 has laid waste to much of what had stood here.

Crumbling and derelict buildings are to be seen all around, and the roads to and from the city are completely unsafe. With its shambolic air terminal and cracked runway, Malakal airport serves as the only lifeline to the rest of what is the world’s poorest country.

Malakal’s population has plummeted, and few of its former residents now live there. The Shilluk tribe have mostly fled their homes here, and those now living in the much-reduced city are recent arrivals from the Dinka tribe.

Decimated

A trip to the parish church provides an example of what has happened. Previously, the large church was filled to capacity for Mass on Sunday, to the point where the roof had been extended on one side where grass and earth were the floor covering.

When Mass was first heard after the major battles were over, only three or four people were in attendance. Though the South Sudanese parish priest says the number coming regularly has increased to around 50, it is still a world away from the situation before.

Where then are the parishioners?

In many cases, they are just a few miles away in the United Nations Protection of Civilians (POC) camp, where a New York priest presides over a de facto parish community.

Father Mike Bassano is an Italian-American priest of the Maryknoll Fathers, whose ministry has taken him to many challenging and far-flung postings.

Now in his mid-70s, he lives alongside UN staff and other humanitarian workers while shepherding a large flock among the more than 50,000 residents of a camp divided between two of South Sudan’s largest tribes: the Nuer and Shilluk.

Each day he walks through what has grown into a sprawling and decrepit town. Thousands of small shacks abound, separated by narrow paths and small streams of wastewater.

There are improvised markets and small businesses offering everything from hot food to the opportunity to watch the latest big sporting contest.

Young and old call out to the ‘abuna’ (priest) as he does his round of visits. When invited in by a family, he sits in the shade with them. Often there are sick people to visit, including in the very basic and crowded medical facilities.

The camp is growing, as the Nuer White Army remains a large and menacing force nearby.

The food crisis is another factor; people from across the region continue to arrive in the hope of finding security and regular food supplies.

Anti-government militants are far from the only threat. Back in 2016, the Dinka tribe to which the country’s president belongs were present in large numbers within the camp.

In February of that year, weapons were smuggled into the camp to arm the Dinka residents. Then, government soldiers launched an assault on the perimeter, which was soon breached.

Although thousands of Nuer and Shilluk shelters were destroyed, the Rwandan UN forces insisted on receiving a written order before using defensive force.

Twelve hours after the attack began, they finally put the attackers to flight, but in the meantime, 30 people had been killed and thousands made homeless. Afterwards, the Dinka were pushed out of the camp in retaliation.

Many departed for the old town of Malakal, thus leaving only the Nuer and Shilluk, who are themselves on uneasy terms.

Fr Mike’s ebullient personality helps in his work, which is not his first assignment in the area.

Nearly martyred

Prior to the civil war, he was part of a four-person community from Solidarity with South Sudan who had worked to establish a much-needed teacher training college in Malakal.

In mid-December 2013, the political situation deteriorated sharply and it became clear that Dinka and Nuer forces were about to turn the country’s second biggest city into a warzone.

The students had gone home for the Christmas break, but four of the members of Solidarity’s community (drawn from orders from across the world) remained in the school: three nuns and Fr Mike.

As governments scrambled to evacuate their citizens, the community members were asked to vote on whether they would remain at the college or accept free flights out of Malakal. Committed as they were to the task of training the next generation of teachers, the Solidarity team unanimously chose to stay.

It was a fateful decision. On Christmas Eve, the college came under intensifying fire as the two warring factions fought for control of Malakal with tanks, artillery and rocket-propelled grenades.

Leaving the house was no longer an option: people were being shot on sight outside. The community needed shelter, and one guest bathroom with a high window provided relative safety.

It was this room that they would crowd into whenever a gun battle commenced. “Our prayers weren’t very long: Jesus help us, Jesus help the people…” he recalled.

Eventually, the four were evacuated, but within a year Fr Mike had applied to return to Malakal.

The Solidarity teacher training college would remain closed. Although Solidarity with South Sudan’s projects normally involve clergy living in communities, Fr Mike requested a solo appointment to work in the growing refugee camp.

“I asked if I could come; even though I was the only Solidarity member, I told them the Catholic community had no one; the priests had fled, everyone had come to Juba, the sisters, the priests. There is nobody there for the people in the camp.”

Permission was granted, and to Malakal he returned. Eight years on, he has become — in essence, if not in name — the parish priest of the POC.

Serving the suffering

Here the poverty which exists is of the most visceral kind. New arrivals often appear famished, and the usual diseases associated with war and famine are common. Men limp around with horribly twisted limbs which in another country could be operated on, but which here bring a life sentence of suffering.

As he walks through one of the main thoroughfares, a crippled little girl of about six passes nearby. She moves on all fours along the filthy ground, with improvised knee pads providing some protection.

Malakal’s people are remarkably cheerful in spite of everything, but the circumstances of life have hardened them.

Waiting outside Malakal’s battle-scarred airport terminal, Fr Mike is approached by a soldier from his church. His son has died in Uganda, he tells him, the eldest of his boys. Now he is travelling to the funeral.

“God gives, God takes,” the middle-aged man says simply. He bows his head and receives Fr Mike’s blessing for his late son, crosses himself and walks silently back to his seat, wiping tears away.

Suffering is everywhere, but Fr Mike’s rationale for choosing to stay here goes to the heart of his faith. He said,

“As a young boy, when I went to the church and saw the crucifix of Christ, I would look at the cross and I didn’t think ‘Jesus, why did You die for my sins?’ As a kid, not that it didn’t make sense, but I understood that: why did You do that? To let us know that You’re always with us, and any kind of suffering, if You could go through it, You would give us the strength to face any challenge in life.”

Unusual unity

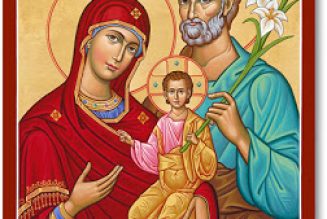

There are many churches within the POC, but Fr Mike’s metal-roofed building — constructed using funds from his order — stands out in one important respect.

Whereas Protestant churches in the camp are divided along tribal lines between the Nuer and Shilluk residents, Fr Mike has succeeded in creating and maintaining a cross-tribal Christian community which is flourishing.

Upwards of 1,000 people come to the Holy Family Church each Sunday wearing their best clothes and putting what little they have into the collection plates. Mass is in Arabic for the most part, and the Nuer and Shilluk languages are both avoided in order to maintain neutrality between the groups. There is no obvious division in the pews.

In what should be a hopeless place, the congregation appear immensely hopeful.

It is a growing community — around 120 people in the camp are currently being prepared for baptism — and one where residents of the camp play an active role through the parish council, an active Legion of Mary praesidium, and a large and popular choir whose rehearsals on Saturday evening draw a good-sized crowd. On Sunday, the differences the people have can be temporarily forgotten, and a better world can be imagined.