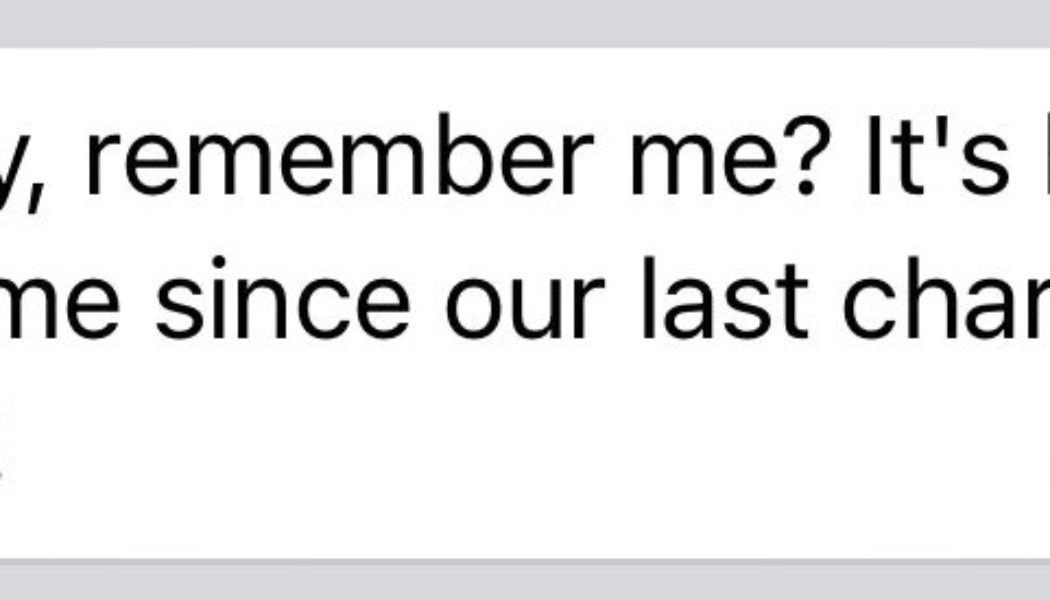

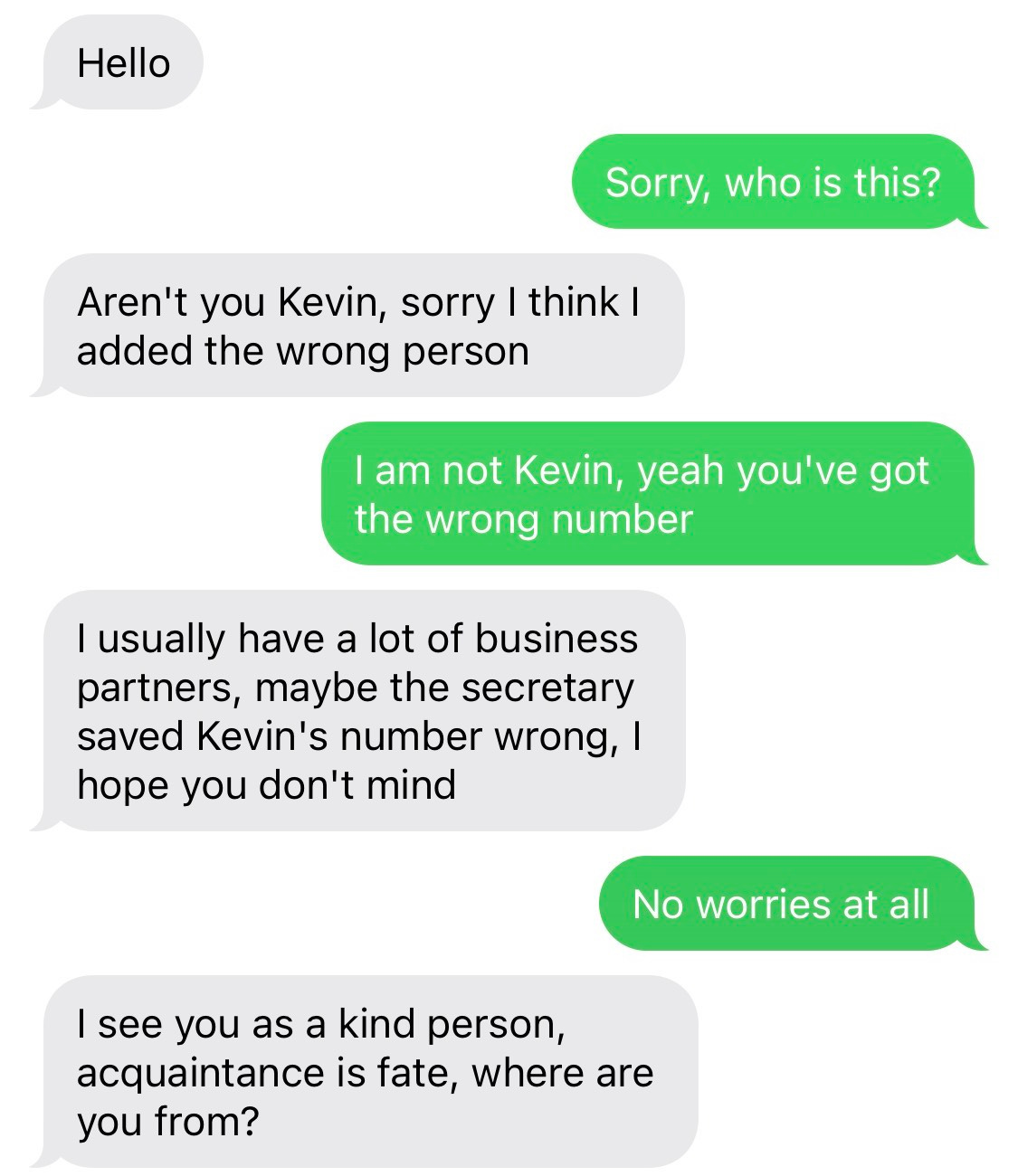

A few months ago I received the following WhatsApp message from a number I didn’t recognize:

Even thought it was clear this message was the lead-in to a swindle of some kind, I had to pause and admire the craft that went into its composition. Like everyone else, I get scam text come-ons pretty frequently, and they’re always poorly pitched and low-energy. In contrast, this text opened up a rich world, animated by detail and alive with mystery. I didn’t care about packages missing their intended destinations, or Bitcoin investing advice, or whatever scammers usually texted me about, but I was interested in Tony: How many charity galas did he go to, anyway? And why hadn’t he seen his/my unknown interlocutor in such a long time? Before I reported the number to WhatsApp, I took a screenshot of the message to better remember it.

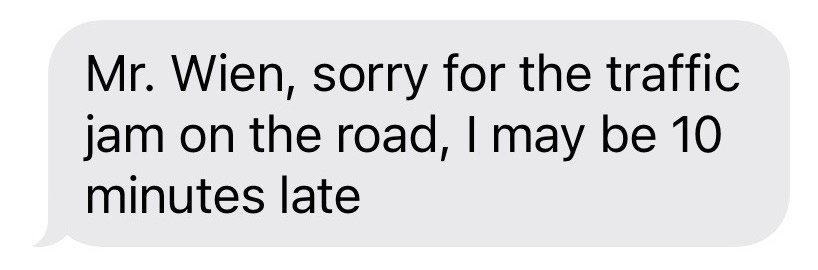

But I didn’t really need to. Over the next several months, alongside the spam calls and texts, I kept getting mysterious wrong-number texts, all of them clearly from scammers, but without an obvious angle. Nevertheless, they shared with the original charity-gala text a literary sense of narrative tension:

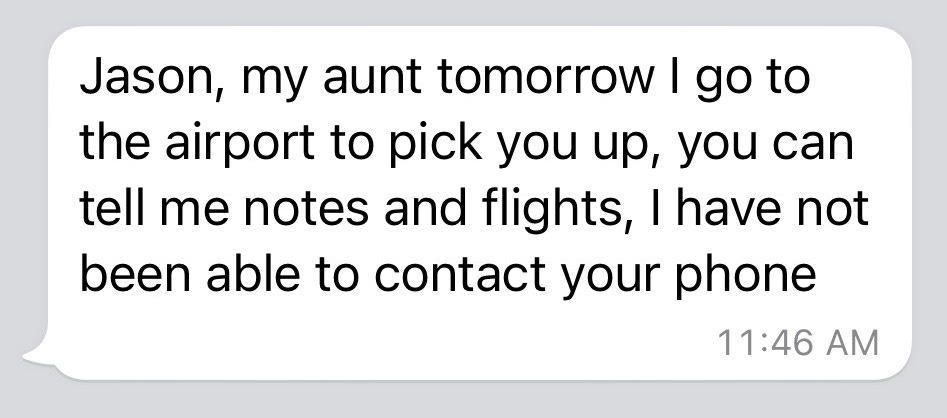

I am not the only person who has suddenly found themselves flooded in these mysterious texts. Last weekend my friend Mark Slutsky and I were texting some of our favorites back and forth, including this particularly intriguing one that Mark received:

There’s something to be written about here, Mark texted. What is the deal with these texts? Why do they sound like that? Who is sending them?

The Pig-Butchering Scam

The fact that these scammers never include the pitch in their opening texts makes them seem confusing and mysterious. But the scam itself is an old and obvious one. If you respond (with “wrong number,” say) the scammer will attempt to draw you into conversation, as in the below exchanges, provided by readers:

This is the first step in what is, at its core, an old-fashioned “romance scam,” in which the scammer exploits a lonely and/or horny person by faking a long-distance, usually romantic relationship. After the scammer has gained the trust of their victim, they convince them to transfer money, often for an investment; in some cases, the victim can be enticed into several successive transfers before they realize they’re being played.

This kind of con has proliferated over the last few years in China, where it’s called sha zhu pan, or “pig-butchering,” because the victim is strung along for weeks or months before the actual swindle, like a pig being fattened for slaughter. Originating in sophisticated online-fraud networks first developed to take advantage of Chinese offshore gamblers, the sha zhu pan scams end with targets depositing money into forex or gold trading — or, seemingly most commonly, into fake cryptocurrency platforms. (Interestingly, they’re often not “romantic” at all, and instead rely on cultivating a trusting friendship that culminates with a little bit of friendly investing advice.)

While sha zhu pan scams are common enough in and around China that there are Chinese-language YouTubers whose stock in trade is identifying and publicizing scams, the same scam networks seem to have expanded outward over the past year or so, joining America’s (and Europe’s) own homegrown romance and crypto-scam industries on dating sites and, yes, via “accidental” wrong number texts. Here’s a poor guy on Reddit who lost money after taking the advice of a “beautiful Korean woman” who “accidentally” texted him:

Hello fam. i have a south korean beautiful woman who “texted the wrong number”

We talked for a while and we have trading (crypto) in common now. She assisted making an account on a OTC website for trading crypto. Everything is very shady and kindness like this doesnt exist. Weve made certain trades and its gone through and ive make money but this is super sketch need some help.

In this case, the victim deposited the money into a fake crypto platform that told him his investments were performing well, presumably to entice him to deposit even more. Of course, once he tried to withdraw the money, he found he was unable to. In the comments, a near-victim describes the process in more detail:

i was the victim of a chinese badass scam, That chinese woman texted me ‘by mistake’ and she has an uncle who taught her trading, she lives in new york for 20 years but originally from hong kong, studied finance and she’s a business owner, she was fattening me for two weeks then she wanted to mentor me and help me earn money, she was obviously using google translate because she was quitting WhatsApp every minute and then translating to English then she pastes the message, which made me even more suspicious: how come she’s been living in new york for 20 years and she’s using translator? i got fattened and was prepared to be slaughtered and once she asked me to send money to this website: flxbank.com , i started researching it and i found a post on reddit that got me educated about it! Reddit’s community literally saved me 700$!

The scam’s pattern is the following:

– She texts you ‘by mistake’, she keeps talking to you and befriending you, she asks you a lot of questions about your life, she keeps telling you about her successes, trades and profits, she also said that she gives 20% of profits to charity and wants to mentor me to trade under one term- give 20% of profits to charity, which was a big point that made me believe her.. but in fact, 100% of profits\’invested’ money is going to the scammers, to fund the scam and hire more scammers and expand their criminal businesses.. she almost gained my heart but her progress and her slaughtering got halted when i’ve read an amazing article on a wonderful and remarkable website, ‘reddit.com‘.

Another, even longer description of the scam from the point of view of a near-victim can be found here. A wonderful and remarkable website, “reddit.com.”

The texts and scripts

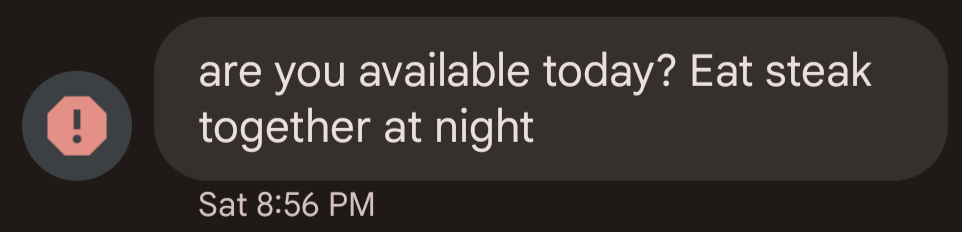

These descriptions of the scam’s progression make it clear why the world-building detail in the opening salvos is so important: Who wouldn’t want to take investment advice from someone who goes to so many charity galas they can’t remember the last time they went to one with Tony? This text, for example, suggests its author belongs to a network of successful property owners:

While this one is from a clearly very busy executive in England:

Possibly this person’s “business meeting” is related to the “business work” at which this texter toils:

Business numbers, are, naturally, given out freely…

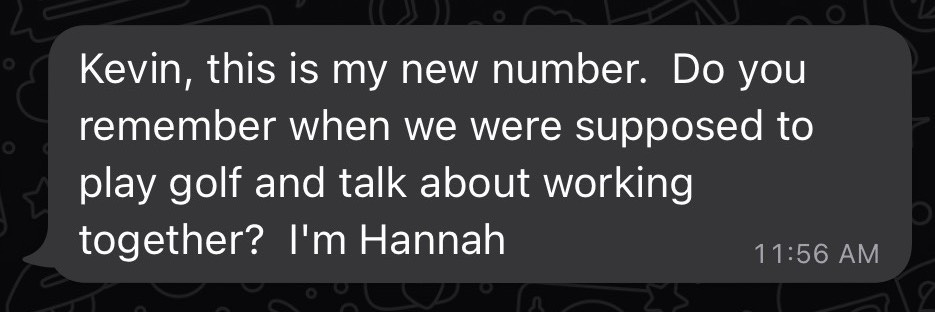

…as are, unsurprisingly, invitations to golf:

The best message of all, however, is the following:

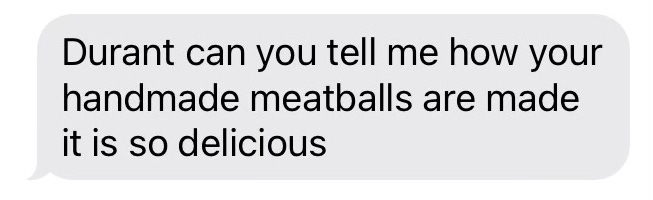

Can you think of a text that more compactly communicates that you are dealing with a person of great wealth and sophistication than “Andy, will my custom mahogany furniture arrive next week?”

Except maybe this one?

The texts don’t always rely on signifiers of wealth like “eat steak together at night,” though often when you respond “wrong number” the scammer will blame an unnamed assistant, to better communicate to you that you’re texting with a big shot.

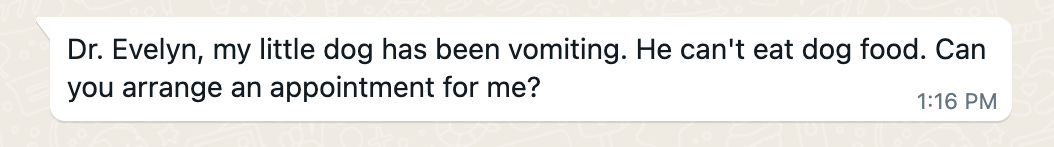

Sometimes they are simple sympathy plays, often concerning pets. What kind of hard-hearted person would decline to respond to a wrong-number text like these?

And then sometimes — as with the text Mark received above, directed toward Durant — you’re simply thrown strange curveballs:

As you might guess from the consistency of the themes (and in some cases the identical wording), sha zhu pan scammers, working across multiple phones and accounts, use scripts and handbooks like any professional telemarketing organization. Some of these documents have allegedly leaked, often published by the Global Anti-Scam Org, an anti-scam group founded by a Taiwanese scam victim that collects and translates material on these scams from Asian outlets and social media. Excerpts from one such handbook, supposedly a training manual from a sha zhu pan scam network, were posted to Reddit; here’s advice on how to “cut in” on the victim:

Three, how to cut in

1. I am making extra money (lots of free time, does not affect regular chatting)

2. I am looking at trend/candlestick charts (preparing to make money on WeChat)

3. I am waiting for a friend to make money (waiting for him to draw up an investment plan on WeChat)

4. I am going to teach my relatives and friends to make extra money (always let her help her make money, and [she] cooks for me everyday to please me)

5. I just placed a bet (after the enthusiasm has peaked pause for one minute, and then speak)

6. Profit screenshot

Send two pictures of luxury bags or jewelry to the guest and ask the guest to help choose one, hinting to the guest that one has recently made a considerable amount of extra income and wants to buy a gift for family.

Choose two tourist attractions to go to and let the customer choose one, to imply to the guest that you have recently made some impressive profits from the sideline and want to reward oneself.

Send high-end restaurants to comment on their expensive and unpalatable meals. Better off to stabilize the side income first, or it’s too wasteful.You can ask the guest what they usually do when they are bored. After the guest answers, they will usually ask you what you have done and you will have a chance to get in.You can say: travel, walking the streets/window shopping, listen to music, play mahjong, making money on WeChat, etc. [or whatever platform]

I haven’t seen any handbooks or scripts that include any of the wrong-number texts reproduced here, but GASO has another very detailed one here, leaked by a Nepali translator, and here’s another one that appeared on Reddit. Also floating around on Reddit and Chinese social media are screenshots, purportedly of conversations between scammers and anti-scam “scambaiters,” who try to entice scammers into confessions that they then post online. In this one one a scammer complains he has only five phones, and shares a screenshot of the victims he’s talking to at the moment:

To be clear, I can’t independently confirm that any of these screenshots or supposed leaked documents are what they claim to be, but I don’t on the other hand have a particular reason to doubt them.

The dog-pushers

As you can imagine from the elaborate handbooks and detailed scripts, the pig-butchering scams that emerge out of wrong-number texts aren’t the product of individual con artists or even of small informal groups. Rather, as has now been pretty extensively documented in the Asian press, they’re a key revenue stream of large hierarchical organizations — fraud businesses, basically — based in Southeast Asia. Worse, the “dog-pushers” — the lowest-level scammers who initiate conversations with victims — are often workers from around the region, tricked into indentured servitude, held captive in dormitories and offices, and beaten by the managers and bosses.

Nikkei has an excellent long article focusing on the trafficking situation in Cambodia in particular. Workers — mostly in China, but also in Malaysia, Thailand, India, and elsewhere — respond to job advertisements on Wechat or Facebook for, say, customer service; they’re smuggled into Cambodia (or elsewhere) and find themselves trapped and forced to work:

A supervisor gave him a cellphone, showed him to a computer and told him to download Chinese social networking apps. Each day, until the early morning, he was told to befriend women in China, gain their trust and entice them to invest in bitcoin.

Every few days, the bosses held performance meetings. Earners would be rewarded, allowed to start late. People whose work was deemed unsatisfactory would be beaten.

“We were either sleeping or eating or we were working,” he told Nikkei.

Captives are subjected to violence and torture, which is sometimes filmed and sent to relatives to spur them to send ransoms. Some have been killed and their deaths reported as suicide, according to workers who have escaped.

Some are sold between companies. Prices start at around $8,000 but vary depending on the financial means of a victim’s family.

Some (graphic) videos of dormitories, offices spaces, and violence the kidnapped workers can be subject to have been uploaded to the Chinese social media site Zhihu here.

Not all the scammers are unwilling victims, of course. The fraud rings are often offshoots of shady online gambling groups, run by and catering to Chinese nationals but based elsewhere in the region, in places like Sihanoukville, a coastal city in southwestern Cambodia. (Gambling is banned in China outside the state lottery.) Sihanoukville boomed between 2016 and 2019, as casino operators fleeing a crackdown in the Philippines opened up shop, but when Cambodia banned online gambling (apparently under pressure from the Chinese government), Sihanoukville’s growth seems to have stalled. What could be done with all those new buildings? According to The Straits Times, describing a police rescue of 16 captive Malaysian workers:

Based on photographs seen by The Sunday Times, the syndicates take over abandoned high-rise buildings, which are heavily guarded and fenced up. Within those walls, scammers of various nationalities contact hundreds of people daily via social media platforms, hoping to find scam victims.

To ensure they do not escape, those working in the syndicates are kept under tight surveillance, with CCTVs everywhere and workers’ phones checked regularly. Ah Heng said he had enough to eat but living conditions were filthy.

Authorities — and sometimes private citizens — regularly mount “rescue missions,” often ultimately paying a “redemption fee” (something between an indenture and a ransom). This wild GASO report of an operation to reunite a Taiwanese father and son in the Dara Sakor resort development seems like a not-atypical story: the team of journalists and human-rights activists (and, naturally, YouTubers) had their photographs leaked to the scam ring by the police, and were forced to aggressively negotiate for the kid’s freedom as the bosses were trying to sell him to a different fraud ring in Sihanoukville. (And, after all that, GASO suggests that maybe the kidnapped kid was not as unwilling as he’d originally claimed.)

Andy, will my custom mahogany furniture arrive next week?

So, to answer our question: What’s the deal with the weird wrong-number texts? These texts are usually the lead-in to romance scams that usually end with fake crypto deposits, written so as to imply wealth and success on the part of the scammer, who is often an abused and captive worker operating multiple phones and attempting to con several people from a compound operated by shady gambling rings somewhere in Southeast Asia.

Now what? It seems likely we can expect this species of pig-butchering scam to eventually fade into the background, thanks to victims getting wise and authorities cracking down. An interview with the subject of the GASO rescue mission suggests that the scam rings’ operations in Europe and North America, at least, are not as profitable as they’d hoped:

Zhen Xu was confined and worked inside one of the real estate properties developed by Chinese investors. Reportedly, whole buildings are dedicated to doing online scams. His particular company targeted Americans and Europeans, though with business doing poorly they are turning (back) to the Japanese market. Zhen Xu claims to be bad at scamming so he was assigned as an “assistant supervisor” to a team all composed of Indians and Bangladeshis.

And, just as Sihanoukville was the refuge of shady operators forced out of the Philippines, increasing crackdowns in Cambodia seem to be pushing the fraud rings (and associated human-trafficking operations) into northern Myanmar:

By the late 2010s, both Cambodia and the Philippines were subject to increasing pressurefrom the Chinese government to rein in the excesses of the online gambling/fraud industry. In order to survive, the sector, especially its more fraudulent sections, needed a highly accessible place where the influence of the Chinese authorities is minimal. Shwe Kokko perfectly fit the bill. It is a personal fiefdom run by Saw Chit Thu’s Border Guard Forces (BGF), which are nominally under the Tatmadaw but practically act as his personal army. This means that although technically under Burmese sovereignty, the area is beyond the effective control of the Burmese state, with no Burmese immigration or customs control on the border and Burmese officials forbidden from entering the area without informing the BGF in advance. In addition, the location has access to the wider world through Thailand’s electric grid, telecommunication network, roads, and airports, while physically and legally separated from it by a river.

These developments, and history in general, suggest that eventually you won’t notice the odd literary plaintiveness of dog-pushers’ wrong-number texts, and sha zhu pan and its abused fraudsters will eventually join old-fashiond viagra spam, classic Nigerian 419 fraud, group-text touts, and, of course, the daily chime of spam calls warning you about expired car registration or outstanding insurance premiums as another tone in the great background hum of scammery, injustice, and abuse that makes up contemporary life.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity