Reading “The Screwtape Letters” can be a creepy and unsettling experience because C.S. Lewis does not merely take us into the head of the human who is experiencing temptation, but into the malevolent mind of the devil himself. This same psycho-dramatic technique is employed by the directors of the recently released horror film, “Nefarious,” in which a serial killer appears to be demonically possessed.

Perhaps the darkest of all C.S. Lewis’s works and probably the strangest is The Screwtape Letters in which the narrative voice is that of a demon giving instructions to a junior devil. Throughout its pages, Screwtape teaches Wormwood, the novice demon, how to work and worm his way within the mind and emotions of his human victim, offering suggestive rationalizations and excuses for sin. The satanic mission of this demonic duo is nothing less than to lead their victim into temptation as a means of bringing about his damnation. Their actions are the very inversion and perversion of the prayer of the Our Father, which are designed to deliver us to the evil of “Our Father Below”.

Perhaps the darkest of all C.S. Lewis’s works and probably the strangest is The Screwtape Letters in which the narrative voice is that of a demon giving instructions to a junior devil. Throughout its pages, Screwtape teaches Wormwood, the novice demon, how to work and worm his way within the mind and emotions of his human victim, offering suggestive rationalizations and excuses for sin. The satanic mission of this demonic duo is nothing less than to lead their victim into temptation as a means of bringing about his damnation. Their actions are the very inversion and perversion of the prayer of the Our Father, which are designed to deliver us to the evil of “Our Father Below”.

Reading The Screwtape Letters can be a creepy and unsettling experience because Lewis does not merely take us into the head of the human who is experiencing temptation, but into the malevolent mind of the devil himself. This same psycho-dramatic technique is employed by the directors of the recently released horror film, Nefarious, in which a serial killer appears to be demonically possessed.

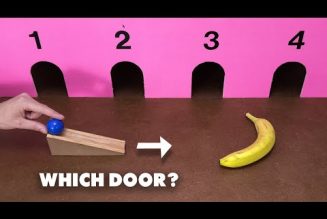

Based on the novel, The Nefarious Plot, by conservative talk show host Steve Deace, the plot of the film focuses on the efforts of an atheist psychiatrist to discern whether a serial killer on death row is faking his claim to be possessed by a demon as a way of escaping his imminent execution on the grounds of insanity. The psychiatrist, played by Jordan Belfi, is outmatched by the killer, played by Sean Patrick Flanery, as it becomes increasingly evident that his philosophical denial of supernatural reality and his scientific skepticism is no match for the diabolus which inhabits the body of the killer.

Flanery’s portrayal of the possessed murderer is nothing less than masterful. When the demonic presence is in the ascendent, which is most of the time, we are reminded of the chilling brilliance of Anthony Hopkins’ portrayal of Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. The diabolus demolishes the facile philosophical presumptions of his supercilious interlocutor, outwitting the psychiatrist’s narrow scientism and atheism with cold and chilling reason. Especially brilliant is the way in which Flanery incarnates the demonic presence in the body language and especially the facial expressions of the possessed man. It’s as though the devil within is disgusted with the physical aspects of humanity. His words spit from the possessed man’s mouth and the face grimaces grotesquely. And yet the words themselves are as clinically persuasive as are the words of Screwtape, the Wormwood within incarnated as Wormtongue. The demonic made flesh and dwelling among us.

During the intensity of the scenes in which the psychiatrist dialogues with the devil whose existence he stubbornly denies, there are moments in which societal evils, such as euthanasia and abortion, are let loose in disturbing twists in the storyline. We come to see and understand that the culture of death is itself a culture possessed by demonic legions. And yet the twists and turns are all done so well. The writing is so top-notch that Nefarious teaches but never preaches. This is the mark of great art which, at its best, exposes the mark of the beast without the didacticism of the Sunday sermon. C.S. Lewis, the past master of such art, would no doubt approve.

Perhaps the most analogically applicable moment, and the most despicably momentous, was the arrival of a Catholic priest into the cell. The demon is evidently disturbed by the presence of this minister of its enemy’s sacramental power, spitting its hatred but also its fear of the power of exorcism. The priest, however, is of the modernist bent, a fact made manifest by the rainbow-coloured scarf around his neck, worn perversely like a stole, the symbol of the sexual pride to which he no doubt subscribes. It becomes evident that the priest has much less faith than the demon in sacramental grace and the power of exorcism. Indeed, the demon has no need for faith because it knows such supernatural power as a fact which it is not at liberty to deny. Finding itself in the presence of a priest of little faith who has betrayed his master with a kiss, the demon welcomes this Judas as an ally and a future victim.

Having failed to have offered a spoiler-alert before revealing this close encounter of Judas with the devil, it would be best were the reviewer to desist from further revelations. Let it be said, therefore, that Nefarious has multifarious moments of dramatic power which palpitate with the theological light and life which expose the darkness of the death-culture.

Paradoxically it is often the presence of evil which animates the desire for the good, much as the man in the dark desires the light or as the drowning man desires the air. And so it is that Nefarious takes us into the dark to remind us of the light that conquers darkness. Nefarious is, therefore, an enemy of all that is truly nefarious.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is courtesy of IMDb.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

body{–wp–preset–color–black: #000000;–wp–preset–color–cyan-bluish-gray: #abb8c3;–wp–preset–color–white: #ffffff;–wp–preset–color–pale-pink: #f78da7;–wp–preset–color–vivid-red: #cf2e2e;–wp–preset–color–luminous-vivid-orange: #ff6900;–wp–preset–color–luminous-vivid-amber: #fcb900;–wp–preset–color–light-green-cyan: #7bdcb5;–wp–preset–color–vivid-green-cyan: #00d084;–wp–preset–color–pale-cyan-blue: #8ed1fc;–wp–preset–color–vivid-cyan-blue: #0693e3;–wp–preset–color–vivid-purple: #9b51e0;–wp–preset–color–awb-color-1: rgba(255,255,255,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-2: rgba(246,246,246,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-3: rgba(224,222,222,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-4: rgba(233,168,37,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-5: rgba(116,116,116,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-6: rgba(120,85,16,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-7: rgba(62,62,62,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-8: rgba(51,51,51,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-custom-10: rgba(174,137,93,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-custom-11: rgba(192,153,107,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-custom-12: rgba(190,189,189,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-custom-13: rgba(62,62,62,0.8);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-custom-14: rgba(68,68,68,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-custom-15: rgba(221,221,221,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-custom-16: rgba(232,232,232,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-custom-17: rgba(249,249,249,1);–wp–preset–color–awb-color-custom-18: rgba(229,229,229,1);–wp–preset–gradient–vivid-cyan-blue-to-vivid-purple: linear-gradient(135deg,rgba(6,147,227,1) 0%,rgb(155,81,224) 100%);–wp–preset–gradient–light-green-cyan-to-vivid-green-cyan: linear-gradient(135deg,rgb(122,220,180) 0%,rgb(0,208,130) 100%);–wp–preset–gradient–luminous-vivid-amber-to-luminous-vivid-orange: linear-gradient(135deg,rgba(252,185,0,1) 0%,rgba(255,105,0,1) 100%);–wp–preset–gradient–luminous-vivid-orange-to-vivid-red: linear-gradient(135deg,rgba(255,105,0,1) 0%,rgb(207,46,46) 100%);–wp–preset–gradient–very-light-gray-to-cyan-bluish-gray: linear-gradient(135deg,rgb(238,238,238) 0%,rgb(169,184,195) 100%);–wp–preset–gradient–cool-to-warm-spectrum: linear-gradient(135deg,rgb(74,234,220) 0%,rgb(151,120,209) 20%,rgb(207,42,186) 40%,rgb(238,44,130) 60%,rgb(251,105,98) 80%,rgb(254,248,76) 100%);–wp–preset–gradient–blush-light-purple: linear-gradient(135deg,rgb(255,206,236) 0%,rgb(152,150,240) 100%);–wp–preset–gradient–blush-bordeaux: linear-gradient(135deg,rgb(254,205,165) 0%,rgb(254,45,45) 50%,rgb(107,0,62) 100%);–wp–preset–gradient–luminous-dusk: linear-gradient(135deg,rgb(255,203,112) 0%,rgb(199,81,192) 50%,rgb(65,88,208) 100%);–wp–preset–gradient–pale-ocean: linear-gradient(135deg,rgb(255,245,203) 0%,rgb(182,227,212) 50%,rgb(51,167,181) 100%);–wp–preset–gradient–electric-grass: linear-gradient(135deg,rgb(202,248,128) 0%,rgb(113,206,126) 100%);–wp–preset–gradient–midnight: linear-gradient(135deg,rgb(2,3,129) 0%,rgb(40,116,252) 100%);–wp–preset–duotone–dark-grayscale: url(‘#wp-duotone-dark-grayscale’);–wp–preset–duotone–grayscale: url(‘#wp-duotone-grayscale’);–wp–preset–duotone–purple-yellow: url(‘#wp-duotone-purple-yellow’);–wp–preset–duotone–blue-red: url(‘#wp-duotone-blue-red’);–wp–preset–duotone–midnight: url(‘#wp-duotone-midnight’);–wp–preset–duotone–magenta-yellow: url(‘#wp-duotone-magenta-yellow’);–wp–preset–duotone–purple-green: url(‘#wp-duotone-purple-green’);–wp–preset–duotone–blue-orange: url(‘#wp-duotone-blue-orange’);–wp–preset–font-size–small: 11.25px;–wp–preset–font-size–medium: 20px;–wp–preset–font-size–large: 22.5px;–wp–preset–font-size–x-large: 42px;–wp–preset–font-size–normal: 15px;–wp–preset–font-size–xlarge: 30px;–wp–preset–font-size–huge: 45px;–wp–preset–spacing–20: 0.44rem;–wp–preset–spacing–30: 0.67rem;–wp–preset–spacing–40: 1rem;–wp–preset–spacing–50: 1.5rem;–wp–preset–spacing–60: 2.25rem;–wp–preset–spacing–70: 3.38rem;–wp–preset–spacing–80: 5.06rem;–wp–preset–shadow–natural: 6px 6px 9px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.2);–wp–preset–shadow–deep: 12px 12px 50px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.4);–wp–preset–shadow–sharp: 6px 6px 0px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.2);–wp–preset–shadow–outlined: 6px 6px 0px -3px rgba(255, 255, 255, 1), 6px 6px rgba(0, 0, 0, 1);–wp–preset–shadow–crisp: 6px 6px 0px rgba(0, 0, 0, 1);}:where(.is-layout-flex){gap: 0.5em;}body .is-layout-flow > .alignleft{float: left;margin-inline-start: 0;margin-inline-end: 2em;}body .is-layout-flow > .alignright{float: right;margin-inline-start: 2em;margin-inline-end: 0;}body .is-layout-flow > .aligncenter{margin-left: auto !important;margin-right: auto !important;}body .is-layout-constrained > .alignleft{float: left;margin-inline-start: 0;margin-inline-end: 2em;}body .is-layout-constrained > .alignright{float: right;margin-inline-start: 2em;margin-inline-end: 0;}body .is-layout-constrained > .aligncenter{margin-left: auto !important;margin-right: auto !important;}body .is-layout-constrained > :where(:not(.alignleft):not(.alignright):not(.alignfull)){max-width: var(–wp–style–global–content-size);margin-left: auto !important;margin-right: auto !important;}body .is-layout-constrained > .alignwide{max-width: var(–wp–style–global–wide-size);}body .is-layout-flex{display: flex;}body .is-layout-flex{flex-wrap: wrap;align-items: center;}body .is-layout-flex > *{margin: 0;}:where(.wp-block-columns.is-layout-flex){gap: 2em;}.has-black-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–black) !important;}.has-cyan-bluish-gray-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–cyan-bluish-gray) !important;}.has-white-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–white) !important;}.has-pale-pink-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–pale-pink) !important;}.has-vivid-red-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-red) !important;}.has-luminous-vivid-orange-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–luminous-vivid-orange) !important;}.has-luminous-vivid-amber-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–luminous-vivid-amber) !important;}.has-light-green-cyan-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–light-green-cyan) !important;}.has-vivid-green-cyan-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-green-cyan) !important;}.has-pale-cyan-blue-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–pale-cyan-blue) !important;}.has-vivid-cyan-blue-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-cyan-blue) !important;}.has-vivid-purple-color{color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-purple) !important;}.has-black-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–black) !important;}.has-cyan-bluish-gray-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–cyan-bluish-gray) !important;}.has-white-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–white) !important;}.has-pale-pink-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–pale-pink) !important;}.has-vivid-red-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-red) !important;}.has-luminous-vivid-orange-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–luminous-vivid-orange) !important;}.has-luminous-vivid-amber-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–luminous-vivid-amber) !important;}.has-light-green-cyan-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–light-green-cyan) !important;}.has-vivid-green-cyan-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-green-cyan) !important;}.has-pale-cyan-blue-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–pale-cyan-blue) !important;}.has-vivid-cyan-blue-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-cyan-blue) !important;}.has-vivid-purple-background-color{background-color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-purple) !important;}.has-black-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–black) !important;}.has-cyan-bluish-gray-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–cyan-bluish-gray) !important;}.has-white-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–white) !important;}.has-pale-pink-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–pale-pink) !important;}.has-vivid-red-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-red) !important;}.has-luminous-vivid-orange-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–luminous-vivid-orange) !important;}.has-luminous-vivid-amber-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–luminous-vivid-amber) !important;}.has-light-green-cyan-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–light-green-cyan) !important;}.has-vivid-green-cyan-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-green-cyan) !important;}.has-pale-cyan-blue-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–pale-cyan-blue) !important;}.has-vivid-cyan-blue-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-cyan-blue) !important;}.has-vivid-purple-border-color{border-color: var(–wp–preset–color–vivid-purple) !important;}.has-vivid-cyan-blue-to-vivid-purple-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–vivid-cyan-blue-to-vivid-purple) !important;}.has-light-green-cyan-to-vivid-green-cyan-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–light-green-cyan-to-vivid-green-cyan) !important;}.has-luminous-vivid-amber-to-luminous-vivid-orange-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–luminous-vivid-amber-to-luminous-vivid-orange) !important;}.has-luminous-vivid-orange-to-vivid-red-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–luminous-vivid-orange-to-vivid-red) !important;}.has-very-light-gray-to-cyan-bluish-gray-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–very-light-gray-to-cyan-bluish-gray) !important;}.has-cool-to-warm-spectrum-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–cool-to-warm-spectrum) !important;}.has-blush-light-purple-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–blush-light-purple) !important;}.has-blush-bordeaux-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–blush-bordeaux) !important;}.has-luminous-dusk-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–luminous-dusk) !important;}.has-pale-ocean-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–pale-ocean) !important;}.has-electric-grass-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–electric-grass) !important;}.has-midnight-gradient-background{background: var(–wp–preset–gradient–midnight) !important;}.has-small-font-size{font-size: var(–wp–preset–font-size–small) !important;}.has-medium-font-size{font-size: var(–wp–preset–font-size–medium) !important;}.has-large-font-size{font-size: var(–wp–preset–font-size–large) !important;}.has-x-large-font-size{font-size: var(–wp–preset–font-size–x-large) !important;}

.wp-block-navigation a:where(:not(.wp-element-button)){color: inherit;}

:where(.wp-block-columns.is-layout-flex){gap: 2em;}

.wp-block-pullquote{font-size: 1.5em;line-height: 1.6;}

.has-text-align-justify{text-align:justify;}

.wp-block-audio figcaption{color:#555;font-size:13px;text-align:center}.is-dark-theme .wp-block-audio figcaption{color:hsla(0,0%,100%,.65)}.wp-block-audio{margin:0 0 1em}.wp-block-code{border:1px solid #ccc;border-radius:4px;font-family:Menlo,Consolas,monaco,monospace;padding:.8em 1em}.wp-block-embed figcaption{color:#555;font-size:13px;text-align:center}.is-dark-theme .wp-block-embed figcaption{color:hsla(0,0%,100%,.65)}.wp-block-embed{margin:0 0 1em}.blocks-gallery-caption{color:#555;font-size:13px;text-align:center}.is-dark-theme .blocks-gallery-caption{color:hsla(0,0%,100%,.65)}.wp-block-image figcaption{color:#555;font-size:13px;text-align:center}.is-dark-theme .wp-block-image figcaption{color:hsla(0,0%,100%,.65)}.wp-block-image{margin:0 0 1em}.wp-block-pullquote{border-bottom:4px solid;border-top:4px solid;color:currentColor;margin-bottom:1.75em}.wp-block-pullquote cite,.wp-block-pullquote footer,.wp-block-pullquote__citation{color:currentColor;font-size:.8125em;font-style:normal;text-transform:uppercase}.wp-block-quote{border-left:.25em solid;margin:0 0 1.75em;padding-left:1em}.wp-block-quote cite,.wp-block-quote footer{color:currentColor;font-size:.8125em;font-style:normal;position:relative}.wp-block-quote.has-text-align-right{border-left:none;border-right:.25em solid;padding-left:0;padding-right:1em}.wp-block-quote.has-text-align-center{border:none;padding-left:0}.wp-block-quote.is-large,.wp-block-quote.is-style-large,.wp-block-quote.is-style-plain{border:none}.wp-block-search .wp-block-search__label{font-weight:700}.wp-block-search__button{border:1px solid #ccc;padding:.375em .625em}:where(.wp-block-group.has-background){padding:1.25em 2.375em}.wp-block-separator.has-css-opacity{opacity:.4}.wp-block-separator{border:none;border-bottom:2px solid;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto}.wp-block-separator.has-alpha-channel-opacity{opacity:1}.wp-block-separator:not(.is-style-wide):not(.is-style-dots){width:100px}.wp-block-separator.has-background:not(.is-style-dots){border-bottom:none;height:1px}.wp-block-separator.has-background:not(.is-style-wide):not(.is-style-dots){height:2px}.wp-block-table{margin:0 0 1em}.wp-block-table td,.wp-block-table th{word-break:normal}.wp-block-table figcaption{color:#555;font-size:13px;text-align:center}.is-dark-theme .wp-block-table figcaption{color:hsla(0,0%,100%,.65)}.wp-block-video figcaption{color:#555;font-size:13px;text-align:center}.is-dark-theme .wp-block-video figcaption{color:hsla(0,0%,100%,.65)}.wp-block-video{margin:0 0 1em}.wp-block-template-part.has-background{margin-bottom:0;margin-top:0;padding:1.25em 2.375em}