(Redux)

Earlier this week, Cardinal Dolan of New York published a column in which he reflected on the results of the listening sessions in the archdiocese related to liturgy. In particular, he wrote about the complaint that Masses are “too long:”

Could they be on to something? A liturgical scholar observed to me recently, “The greatest advance of liturgical renewal after the council was the restoration of the prominence and solemnity of the Easter Vigil. But the greatest negative of these last decades has been that every Sunday Mass is now as long as Holy Saturday!”

The dismal stories the people shared with me reached litany length. Now, they tell me, Mass starts with music rehearsal, then an obligatory “greeting” to those around you. By then, we’re five minutes past when Mass was supposed to start. The celebrant will usually give a lengthy introduction; the “Gloria” can exhaust the angelic choir, to say nothing of an unending sung responsorial psalm. The prayers of the faithful can go on forever, with the final petition — for the deceased — added to on the spot as some are dropping dead in front of us. Then we sit and wait awhile for the collection and offertory procession. The “Lamb of God” can reach the length of a baseball game. Often, we add a “reflection” after communion, with subsequent announcements. Don’t forget the long list of “thank you’s” for all those who had a part in Mass. God forbid we would leave before all five verses of the closing hymn are sung . . . and I have not even mentioned the biggest culprit of all — the mammoth homily from priests and deacons who ignore Pope Francis’ admonition to keep homilies at 8 -10 minutes!

Much discussion on Twitter/X ensued, and I could write a few thousand words – and have, over the years – on the issues Dolan mentions.

But I think everything I would have to say comes down to the topic of this blog post: It’s not the reverence – it’s the ego.

For every one of the issues Dolan cites can be tracked back to the victory of ego – the celebrant’s, the musicians’, the liturgical planners.

That is not to say that a lengthy liturgy is necessarily the consequence of ego, and honestly a focus on length avoids the real issues.

For a lengthy liturgy in any cultural setting can certainly be an act focused on worship of God, and globally, outside the Western world, tends to be that.

The Mass I normally attend – Novus Ordo, but with lots of Latin, chant and 10-12 minute homilies – is never less than 75 minutes long, is packed, noisy with kids (“the baby choir” as one celebrant memorably and cheerfully described it) and almost everyone stays to the very end of the last verse of the final hymn, of which we do, yes, sing all the verses, sorry, Cardinal – “God forbid we would leave before all five verses of the closing hymn are sung…”

The point is – most of the particular features Dolan points out – features of our suburban Western Catholicism – are all about the centering of the self.

Further, as I also have banged on about for years, ego is what is just waiting to happen when you emphasize the spontaneous action of the Spirit over given liturgical forms or even – hate to tell you – the “needs” of the “local community” in liturgical celebrations, especially in cultures where there is, you know, no culture to speak of.

So when you have a liturgy, you have ministers. You have people in charge. And it is not shocking at all that in a context of being told that The Spirit will work through your words and actions – trust it – you immediately construct a huge, boundless playground for the Ego.

The Ego that at one point might have been constrained by strict rules about obeying rubrics, not to speak of the use of a foreign, non-vernacular language, is unleashed, not only by the fateful “in these or other words” – but by his new role, in constant dialogue with the congregation, who now spend an hour or more gazing on his face, and who has been taught that, in some crucial way, the congregation’s spiritual experience at this liturgy depends on his personality – that his personality and interaction holds a key to a fruitful spiritual moment.

But there’s more.

One of the stated purposes of the conciliar liturgical reforms (growing from the Liturgical Movement) was to help the faithful see the sacredness of the moment – by breaking down the wall between the altar and the pews, that would work to help the faithful bring the sacrality found in worship out into their individual lives and the present moment. Again, isn’t it more impactful, with this goal in mind, to give people liturgy that reflects the current moment in that community’s life rather than something that reflects the experiences of 16th century hierarchs?

How does this work out in real life?

Well, in real life, this grand theory is put into practice by a small group of people – depending on place and time – celebrants, lay ministers, worship committee, musicians – who are operating out of a set of perceived needs and agendas – theirs. It can be little else. Oh, some people have a more expansive vision, but most don’t.

And of course, these people in charge of liturgies are human beings.

How many times have we seen this, in liturgies and in general church life, when leaders, both lay and clerical, have centered their efforts, words and plans on particular agendas and causes, while in front of them sits a congregation gathered with their broken hearts, fears about life and death and all of it, addictions, disappointments, temptations, frightening diagnoses and exhaustion – wondering why they can’t just pray?

To me, it’s an interesting extension of the post-Enlightenment centering of human experience in the cosmos. In a Catholic context, it took different forms, as theological and spiritual thinkers cycled through various angles and anthropologies over the past two centuries, all of which prioritized human experiences of the present moment as the portal to truth and authenticity.

The trouble is – well, one of the troubles – is that given the opportunity, human beings, especially human beings given positions of power and leadership, and encouraged to let the Spirit speak through the present moment and the uniqueness of their own experience, will do just that – imposing their own understanding of the needs of the present moment on the community as normative and fundamental, using the call to inculturate as an invitation to construct a narrative that serves their own purposes and concretize an agenda when all we really came for was the Creed.

I’ll finish of what is turning into a clip episode of this blog by reprinting much of a post I wrote two years ago in relation to the recently announced Eucharistic Revival.

Here. I’ll save you time, anticipating some (justified) tl;dr responses:

For decades, Catholics have been taught, essentially, in word and practice:

You are fine as you are, because God made you that way. God desires you to live eternally with him, and will find a way to bring you to him. What happens in church is good and special, but you can be in God’s presence anywhere and anytime. We sure want you to come, and it might add value to your life experience, but it’s not actually necessary, even if you’re Catholic.

So…why go to Mass?

Let’s paint a picture of the past six decades of Catholic life in America. First, a seemingly small point, but I believe actually quite important:

- Collapse of the Catholic school system, both in terms of numbers and Catholic identity. No, not all Catholic children were educated in Catholic schools especially after 8th grade, but the difference over the past decades is profound and undoubtedly has an impact. Instead of a large percentage of Catholics having experienced, as children, almost daily formal catechesis and, for many, daily Mass, the vast majority of Catholics experience a few years of weekly catechesis, most centered between the 1st and 8th grades, in perhaps 20-30 sessions a year, some not even coming to Mass during that time (ask any DRE about that).

I think that’s key – and know that I’m not a “product” of Catholic schools myself, having attending only a Catholic high school. Most of my formal childhood catechesis was in the 60’s and 70’s mode of – bring newspaper clippings to class and we’ll rap about them (that was 5th grade CCD in Lawrence, Kansas in 1970).

Nonetheless, with the widespread decline of Catholic education, you’ve lost a core population formed in daily “liturgical living” thanks to their schooling.

Let’s expand. Let’s look at the broader landscape of what Catholics heard and learned over the past decades, via church, culture and society, leading up to the present situation of low Mass attendance and low levels of belief in what’s going on there in Mass:

- Eternal life is a given. For almost everyone, The good kind of eternal life, that is. Hell exists (maybe?), but there are very few life choices that will get you eternal damnation. And by “everyone” we mean “everyone.”

- There are countless paths to eternal life, which makes sense since it’s almost just an effortless, natural extension of earthly existence. God loves all, desires all to dwell with him in eternity, and extends his grace without exception to all. Everyone is destined for eternal life with God.

- There are various paths to this end, various ways of understanding and expressing truth. The Catholic faith may be very, very true and quite helpful (and fun! and beautiful! and culturally important! and weird in a fun way!) but it’s not the only way.

- Of course God is everywhere – and so you can experience Him everywhere and anywhere.

- Authenticity and truth is determined, most of all, by emotional response and perceived psychological well-being, not by life lived in the light of any objective reality. God made you, made you just as you are, and loves you just as you are.

- It’s good to be involved in spirituality and faith because that – God’s love of us – is confirmed and experienced. But it’s not the only way, of course.

- What we hear and read in Scripture – what’s proclaimed to us every Sunday in Mass – is primarily interesting and important for what it tells us about how those local communities believed they experienced God in their time and place. What we read in Scripture – even the Gospels – is a product of a particular time, place and understanding. What we’ve heard for decades is not so much Jesus tells us but Matthew’s version of what Jesus says tells us….

- Human life on earth is characterized by progress of all kinds, and the Church is not exempt from this process. We are not living in the 4th or 14th centuries, guys. Life changes, and so the Church changes, too. And that change has a positive value: progress. So is there actually unchanging truth? Maybe, maybe not. Shrugs.

- Faith is not primarily adherence to external beliefs. It is primarily a relationship with God which is personal and not subject to the judgment of others. The primary criterion for evaluation your own faith life is emotion and your sense of acceptance and peace.

To put it in fewer words:

You are fine as you are, because God made you that way. God desires you to live eternally with him, and will find a way to bring you to him. What happens in church is good and special, but you can be in God’s presence anywhere and anytime.

So…no, the Eucharist is not, in this context, crucial. It’s nice, it’s a signifier of membership in one of the many ways to eternal life, but since eternal life is sort of automatic anyway, it ends up being just one of many, potentially equally helpful, options.

And the problem is that so much of that “new” thinking isn’t really new at all, and can actually be found in traditional Catholic faith, but that traditional Catholic faith was, via centuries of organic development, carefully balanced. But in this present moment of the firmly swung pendulum and a disdain for theological niceties in favor of generalized abstracted narratives – we’re left scrambling to find a reason to keep doing what we’re doing if everything is true anyway.

In an essay on this effort, Fr Robert Imbelli, SJ wrote:

Thus, “who do you say I am?” remains the crucial question antecedent to any meaningful examination of belief in the Real Presence or participation in Sunday Eucharist. For one’s response to that question will determine the importance attached to the sacrament. If Jesus Christ is merely an exemplary human being from a remote era, then claiming to encounter him really present in the Eucharist is wishful thinking and liturgical pretense.

Now.

Take into account the impact of church practice:

- What casual, personality-centered liturgies communicate about the Eucharist. Despite good intentions, perhaps they communicate first, that what’s going on really isn’t all that important after all. And then they might also communicate that this Real Presence of Jesus of which you speak isn’t actually as important as my presence – whether I be the celebrant who won’t shut up and believes your spiritual experience is dependent on him making eye contact with you and emoting properly, the self-serving musician or even the complaining, hard-to-please congregation.

- When you make the liturgy something that’s up for grabs in so many ways, you open the door up for human ego that seeks to celebrate and center itself rather than to serve and humbly give glory to God. Again: whose presence is most important here, anyway?

- Catholic indifference to evangelization, both large and small-scale (i.e within parish boundaries). If this Real Presence is so real and so important, why do you guys just endlessly talk amongst yourselves?

- Counter-witness of all types. Most notably: If this Real Presence is so Real, why aren’t you trembling in fear before that Presence instead of protecting abusers of children and then strolling out from that meeting with the attorney and celebrating Mass with a big, welcoming smile on your face?

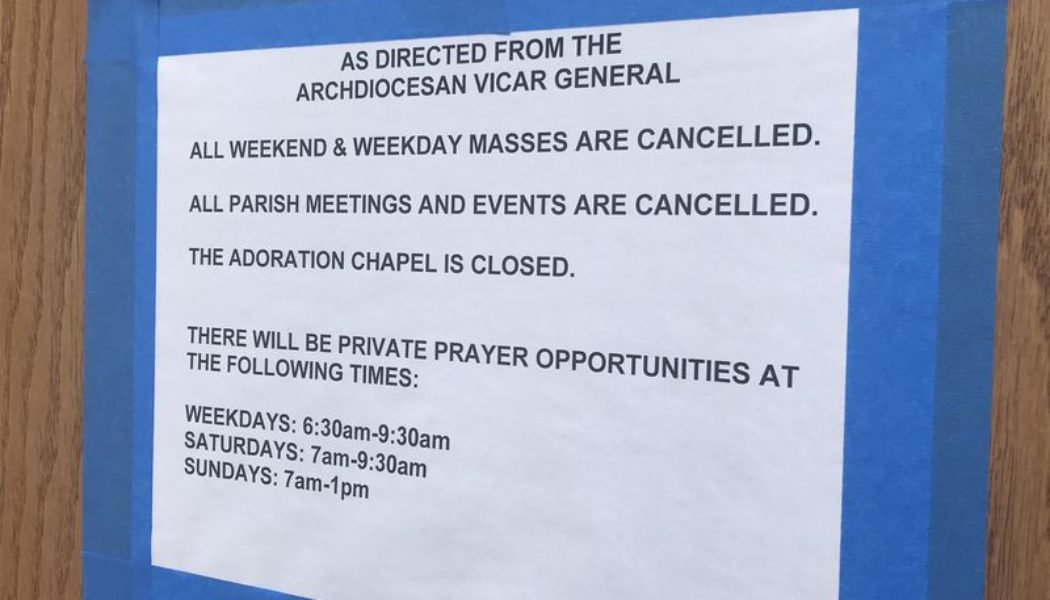

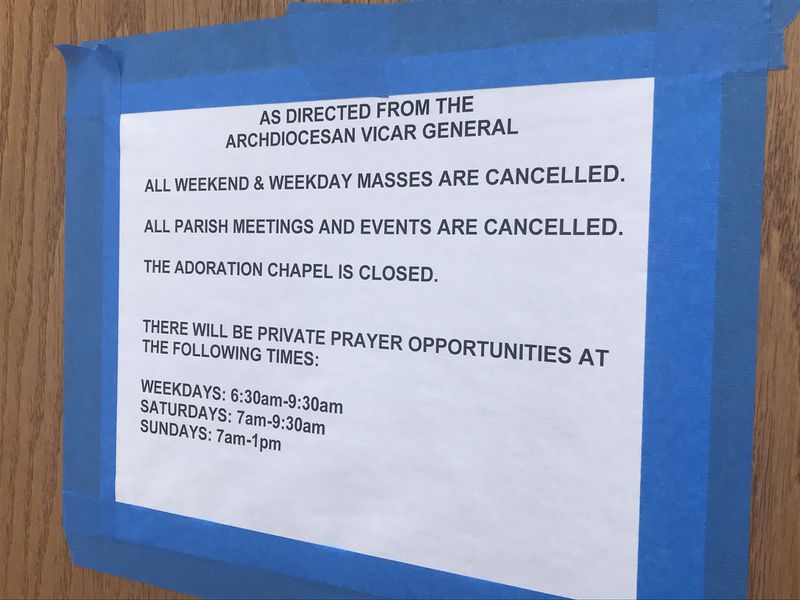

- And then finally: shutting out the faithful from churches, depriving them of the Eucharist – this super-special-Eucharist – for months or longer. What were you guys telling us when you unquestionably complied and locked those doors and made so few creative efforts to bring the Eucharistic Christ outside, to a hurting world?

If the Eucharist wasn’t necessary then ….is it really ever necessary?