WASHINGTON, D.C. — WAR, what is it good for?

For Edwin Starr, the answer was “absolutely nothin’” — although “somethin’” might be a better answer, since he had a No. 1 hit with the tune in 1970.

But for Dominican Father Humbert Kilanowski, he’s got a different answer, because he’s asking a different question.

Kilanowski, a mathematics professor at Providence College in Rhode Island, has been a baseball stats guy since his freshman year in high school, when he was a student manager of his school’s baseball team. “I played up to eighth grade, but I wasn’t any good,” he confessed.

Back then, he remembered, the new big-deal stats were WHIP and OPS. For the uninitiated, WHIP stands for walks plus hits per inning pitched, a measure of a pitcher’s ability to keep runners off base. OPS stands for on-base percentage plus slugging percentage; the former gauges how often a player gets on base per plate appearance, and the latter calculates how many bases the batter collects per at-bat.

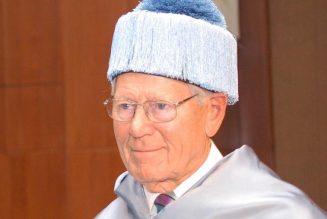

Father Humbert Kilanowski, an assistant professor of mathematics at Providence College, is seen in this undated photo. His love of math and baseball helps him develop new baseball statistics. (Credit: Courtesy Father Humbert Kilanowski.)

Ordained in 2018, Kilanowski not only teaches, but helps out with campus ministry and with a Dominican Third Order group in Rhode Island. He also learned, to his delight, the order has a house on Cape Cod, which gave him a chance to see about a dozen games last year in the Cape Cod League.

The league is one of several “collegiate” leagues around the United States where college ballplayers who think they have a chance in pro ball spend a couple of months in the summer to sharpen their skills. It also gives hitters experience with wood bats; virtually all school and amateur baseball today is played with less expensive and longer-lasting aluminum bats.

Which brings us to WAR, which stands for Wins Above Replacement. In the big leagues, its computations are meant to judge a player’s skill over that of his replacement — typically a minor leaguer who would need to be called up to take his spot on the roster.

But WAR wouldn’t work right in the amateur ranks. For one thing, they haven’t even played in the minors, let alone have a chance to get called up to the majors.

With Cape Cod League statisticians supplying him the 2019 season’s data, Kilanowski made some modifications to account for the level of skill and the shorter season, among other things. His results were published in in early July in the Baseball Research Journal, the annual publication of the Society for American Baseball Research.

His results? Outfielder Nick Gonzales emerged with a cWAR — the lowercase “c” stands for “Cape” — of 3.17, head and shoulders above the next-best player’s cWAR of 1.97.

Kilanowski said scouts had wondered whether the gaudy college stats of Gonzales, who played at New Mexico State, were aided by a lower level of competition, aluminum bats or the thinner air in Las Cruces, elevation 3,900 feet above sea level.

But his Cape Cod League performance sealed the deal. “He was drafted in the first round by the Pittsburgh Pirates, seventh overall,” Kilanowski said.

Kilanowski grew up in Darien, Connecticut, a suburb of New York City, and he and his family were “big fans” of the New York Yankees. “Working in (Boston) Red Sox Nation, I call it my lifelong penance,” he said.

Just as he was a latecomer to the world of sabermetrics — the development of analytic measures to quantify baseball performance — Kilanowski was, in his own words, a “late vocation.”

“I was always Catholic, born and raised in the church,” he said. He was in his parish youth group in high school, and went to the Newman Center at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, “but I was just going through the motions in college.” He even remembers a priest telling him on a retreat he should think about the priesthood, “but I didn’t want to consider the possibility.”

Kilanowski said he was “well into graduate school” before he heard the call. He had a friend joining the Catholic Church at that time, and “he knows more about the faith than I do. What am I doing wrong?”

He started going to Mass daily at a Dominican parish in Columbus, Ohio, and that’s when “it made sense,” Kilanowski said in a July 16 phone interview with Catholic News Service. He admired the order’s “strong academic apostolate, strong community life.”

St. Louis Cardinals’ Busch Stadium is seen during a simulated game July 12, 2020. (Credit: Jeff Curry/USA TODAY Sports via Reuters via CNS.)

He was prepared to tweak his cWAR computations for the 2020 season, but the coronavirus pandemic scuttled the Cape Cod League this year. Kilanowski might have been in Baltimore at the time of the CNS interview, but SABR’s annual convention there was postponed a year due to the pandemic. But he is looking forward to the major leagues’ truncated 2020 season, which starts July 23.

He’s made plans to meet up soon with Father Gabriel Costa, a priest of the Archdiocese of Newark, New Jersey, who teaches math and statistics at the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, New York, and has written several sabermetric papers.

“I’m not even the only priest in my own chapter of SABR,” said Kilanowski of his Rhode Island group. Father Gerry Beirne, a retired priest of the Providence Diocese, celebrates Mass for Catholics at the SABR convention when he goes, and runs the trivia contests at the statewide chapter’s own meetings.

Humbert is Kilanowski’s religious name. Born Philip, the combination of his birth and religious names comes close to that of Philip Humber — and the priest completes the thought — “who pitched a perfect game” for the Chicago White Sox in 2012.