Jesus gives us a harsh warning followed by hard comfort in the Gospel for the Third Sunday of Lent, Year C.

Nonetheless, it is real comfort, comfort for the long haul of the rest of Lent ahead, and for the rest of life ahead.

Jesus is saying more than you think he is in Sunday’s Gospel.

Jesus shares two examples from the news. First, he refers to the horrible thing Pilate did to a group of Galileans who, traditionally, are thought to have been insurrectionists. He killed them in such a way that their blood was spilled with the blood of the sacrifices offered at the Temple. This is often suggested to be the reason that Herod and Pilate were “at enmity” with each other.

Second, he gives the example of people killed in an accident, possibly an act of terrorism to protest tax money being demanded for an aqueduct. Scholars suggest a giant tower built to bring water to the people fell, or was made to fall, killing 18.

This is absolutely supposed to remind us of the violent news of our own day. Our Lady of Fatima delivers the same message about today’s wars that Jesus saw in the violence of his day: “Repent!”

Notice what Jesus actually says here, though. When preachers speak of this Gospel they tend to say that it means “bad things don’t happen because people sin.” But Jesus doesn’t say that. He says “do you think they were more guilty than everyone else who lived in Jerusalem? By no means! But I tell you, if you do not repent, you will all perish as they did!”

Jesus doesn’t say that their sins didn’t lead to their downfall. Instead, he says that we all are sinners like them, and we can all expect a similar fate.

The two examples he gives also provide us with the greatest hope imaginable — but more on that in a moment.

Next in the Gospel, Jesus tells the parable of the fig tree to repeat his warning to us.

In his story, an orchard owner comes across a fig tree that has given no fruit, and he asks his gardener to cut it down. The orchard owner is God, and we, like the Jewish people before us, are the fig tree.

We should pay close attention. The Church — the hierarchy, the consecrated people, and the laity, all of us — have failed for decades now to pass on the faith, such that less than a third of people believe in the real presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist, and people have lost the sense of sin, such that the unforgiveable “sin against the Holy Spirit” is at pandemic levels.

What is his attitude toward such a fig tree? “Cut it down! Why should it exhaust the soil?” he asks. Why should God shower graces on a people that does nothing with them? Jesus sees no end for such a people except destruction.

The gardener says, “Sir, leave it for this year also, and I shall cultivate the ground around it and fertilize it; it may bear fruit in the future. If not you can cut it down.”

The caretaker asks for mercy and, apparently, gets it. This is what God had given us — mercy. But mercy doesn’t mean he shrugs off our sins and no longer cares about them. Mercy means he gives us a second chance to “Repent or perish.” Which one we choose is on us.

Then, the readings do something extremely helpful. They reinterpret our Lent — and our life — as a re-enactment of salvation history.

The Second Reading is from St. Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians, and in it he uses an analogy that is more than an analogy. He compares the Christian life to the Israelites following Moses out of Egypt.

- “Our ancestors were all under a cloud and passed through the sea and all of them were baptized into Moses” he says. We too are under God’s protection, after being baptized into Christ.

- They all “ate the same spiritual food and drank the same spiritual drink,” he says. So do we, only much more so: We eat and drink the body and blood of Christ.

- They “drank from the spiritual rock that followed them,” he says. Our thirst is quenched even more by the Holy Spirit poured forth from Jesus Christ on the cross and in prayer.

But Paul wants all of this to be a warning. He says of the Israelites, and us: “God was not pleased with most of them, for they were struck down in the desert.” Here he means the story from Numbers where spies are sent to scope out the land they are entering and all of them, except for Joshua and Caleb, conclude that God is no match for the world — and as a result God allows only Joshua and Caleb to survive.

“These things … have been written down as a warning to us, upon whom the end of the ages has come,” says Paul. “Therefore, whoever thinks he is standing secure should take care not to fall.”

St. Augustine says, “The history of the exodus was an allegory of the Christian people that was yet to be.” That puts us in the same predicament as the Isrealite people — we can either fear the world and compromise, or fear God and stand strong in the faith. Which of these best describes the Church — the hierarchy, consecrated people and laity, all of us — today?

But look further into the readings for Sunday and you find enormous hope.

So that’s the bad news: God expects more of us than we have delivered. But the First Reading from Exodus, shares more about the story of Moses which, according to St. Paul and St. Augustine, is the story of us.

“I know well what [my people] are suffering,” God tells Moses from the burning bush. “Therefore I have come down to rescue them.”

God himself has come down to rescue his people — to rescue us. He knows our weakness. He knows our sin. He knows our failures. So he will come and make it right. For the Isrealites, that meant God followed them as a cloud and a rock, supplying them with manna and water. For us, it means God sent his Son and his Holy Spirit who shower us with grace in the sacraments.

God tells Moses who he is, “I am the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob,” and “I am who am.” He is both a personal God, who knows his people individually, by name — and the ground of all being. He is the one who spoke to Abraham, rescued Isaac, and wrestled with Jacob — and the one who is wholly present, unchangeable, with no past or future, in the eternal now.

For us, he is both Jesus Christ, the one who came in the fullness of time and invades our lives at discrete moments when we turn to him in the sacraments — and he is the one who is everywhere present in all things by his essence, transcendental presence, and power.

And then we get to the real hope.

Last week, the readings paired the flaming torch and urn of Abraham with the transfiguration. God, aglow in the dark, passed through Abram’s cut-up animals, ratifying a covenant that said God and Abraham would be faithful or end up like those animals. Jesus appeared aglow on Mount Tabor after promising to fulfill that promise by keeping both sides of the bargain in his sacrifice on the cross.

This week, Jesus reveals himself to be the great “I am” who comes to rescue us — the eternal God always and everywhere present, but also the God of you, me, my sister, her friend, and every single person we know.

And now, as promised, we return to those examples Jesus gives us in the Gospel, to see how they reveal the greatest hope imaginable.

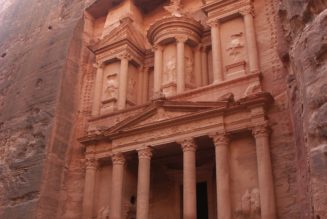

Remember, Jesus refers to the Galileans whose blood was mingled with the sacrifices and the water tower that fell — or was toppled — onto the people. That is an extremely suggestive example. Who is the most famous Galilean whose blood became mingled with Passover sacrifices? Jesus Christ himself. And who was the first person Jesus released with his death? Barnabas, an insurrectionist like those killed for their efforts against Rome. And Herod and Pilate “became friends with each other” over the crucifixion of their mutual enemy, Jesus.

That is the mercy he gives us. We are no better than those who died for their sins and we deserve nothing else, as Jesus said. But he has come to rescue us. And not just to rescue us, but to die in our place. And not just that, but to lead us to the forever promised land flowing with milk and honey, at his side forever.

That is the greatest hope imaginable. He comes to rescue us in the sacraments, he gives us the grace to return to him this Lent, and he pledges to carry us through the rest of our life.

image: kishjar? Flickr

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity