Happy Friday friends,

A bit of trivia for you this morning: on this day in 1954, Ellis Island officially closed its doors for good as an immigration point of entry into the country. In its heyday, some 12 million people came through the island in New York harbor, their first port of call before scattering across the country to make a new life for themselves.

According to the National Park Service, about 40% of Americans can trace their ancestry back to someone who came through its halls. I’ve been there myself to look up a previous Edward Condon on the island’s database and, while it was just a line on a page, it was surprisingly affecting.

One of the more famous arrivals to make it through Ellis Island’s snaking lines was one Maria Francesca Cabrini, better known to us as St. Frances Xavier Cabrini, or, more simply, Mother Cabrini. Mother Cabrini had the ambition to be sent on mission to China, but the pope famously sent her “not to the East, but to the West,” and she arrived in New York charged with care for the thousands of Italian immigrants living in the city in poverty.

She went on to become the first American citizen to be canonized, and her feast is marked in her adopted country tomorrow. Mother Cabrini was, as you’d expect of a saint, a woman of boundless love for those in her care, towering ambition for her assigned work, and an unshakable conviction that the Lord would provide — all qualities worth emulating.

When faced with apparently insurmountable bills for the many hospitals, schools, and orphanages which she opened across the country, she had a habit of simply stamping the invoices “PAID – RETURN TO SENDER,” a saintly dodge which apparently used to do the trick.

Watch this space

The ever-rumbling battle over vaccines got a little more personal for some Catholics this week, especially in the Wisconsin Diocese of Madison.

Bishop Donald Hying had previously issued a statement, saying that Catholic schools and churches in the diocese were not going to host vaccine clincs because, according to the diocesan statement announcing the policy, “by all indications, plenty of secular sites are already available in all eleven counties of the diocese, the diocese has not and will not wade into the polarizing and political environment surrounding this issue.”

“This should not be in any way interpreted as the local Catholic Church or her

leadership discouraging vaccinations,” the policy annoncement said.

Nevertheless, Hying and the diocese drew some sharply critical secular media coverage, perhaps predictably, and also the ire of celebrity campaigner Fr. James Martin, SJ, who called the diocese “anti life” for the decision.

“For Fr. Martin and other critics to attack this decision of the bishop and characterize it as anti-life is at best a case of rash judgment,” the diocese said this morning, “especially considering they did not have the decency to contact him first.”

While the diocese’s frustration is understandable, the reality is that Twitter activism doesn’t often make time or space for context, nuance, or fact-checking, and try as bishops might to keep out of the vaccine fight, they are going to find it a near impossible task. Expect more of this sort of thing to come.

Hard data

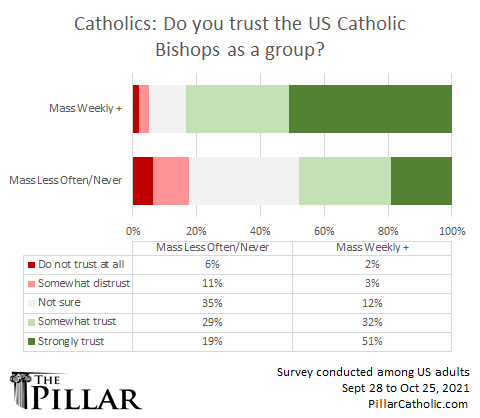

This week, as you have probably noticed, we have given over a lot of space to the results of our first Survey on Religious Attitudes and Practices.

We surveyed a representative sample of Americans, Catholic and non-Catholic, on their views, identities, and religious perspectives. And we’re learning a lot.

We’ve been publishing what we found in a five-part series this week, parts three and four look at religious affiliation and the much discussed rise of the “nones” and Catholic practice following the coronavirus pandemic — do catch up on them, there are some surprises in there:

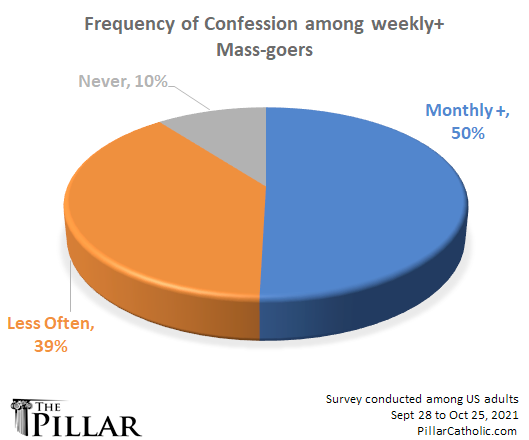

For example, half of weekly Mass attendees reported that they also go to confession at least once a month — not something a lot of people expected to see.

Part five of the survey is out this morning, and it’s probably the most interesting yet.

Of course, our hope is that this is not just of passing or academic interest; we aren’t in the market of making statistical Catholic trivia. Having a clear picture of who we are and what we believe can (should) play a big role in helping the Church live out her mission, both internally and for the evangelization of the world.

And it took a lot of work to get this poll in the field, and a lot more work — the vast majority of it by our contributing editor Brendan Hodge — to sift through the results. So the compliments go to Brendan.

Hard reading

His court rap sheet is horrific enough on its own to inspire much reflection on the need to be ever vigilant in the Church, however far we may have come in recent decades. In addition to using location-based hookup apps to traffic and pay minors for sex, McWilliams also used social media to prey on boys meant to be under his pastoral care, and he engaged in elaborate, truly evil, psychological games which victimized whole families.

One of those families sat with JD and told their story, which we published this week. It’s the longest and hardest read I hope we will ever have to publish at The Pillar. But the courage of this family to tell their story is a service to the Church, and a dire warning about the lessons we have still to learn in the fight against abuse.

It’s not an easy read, but it is an important one. You can read it here.

Derby day in Baltimore

Most of the attention will focus on a document on the Eucharist the bishops are set to debate. We will see what comes of that, especially after they meet for an unusual closed-door session to open the assembly.

But don’t lose sight of the rest of the conference agenda. The chairs of six committees are up for election, including some of the more prominent subject briefs. Floor debate is often dominated by a handful of reliable jack-in-the-box contributors who often find something to say on every issue, but what happens in the committee elections can be a very interesting indicator of how the often silent majority of the bishops actually line up with each other.

Now, it would be grossly impious and inappropriate to compare these elections to our sordid secular democratic process, and I wouldn’t dream of doing so. But a blogger once wrote that my coverage of the USCCB read “like a not entirely sober betting man” talking to his bookie, and, while I am not partial to the ponies myself, it seemed like too good a gimmick for recapping the conference race card to pass up.

To that end, you can read our day-at-the-races preview of the USCCB elections here.

A very political bishop

Last week, I mentioned here that Archbishop Jose Gomez of Los Angeles had made a strikingly direct engagement with progressivist political and social movements.

I noted that, however accurate the USCCB president’s diagnosis might be of the social forces driving wokery, and however clear he was in insisting the Church’s role is to oppose real and ingrained injustice in our society while boldly announcing Christ, some would accuse him of playing at politics — something Pope Francis has appeared repeatedly to discourage.

Well, this week, another U.S. bishop weighed in on our social and political climate, and said he has “always believed that the Church must be political.”

“We do a disservice to our membership if we call for an apolitical Church,” Stowe said, “because that would be a Church that is aloof to the concerns of the human family and just the opposite of how the Church is described in Gaudium et spes.”

“At the same time, I also believe that the Church should be nonpartisan. Catholic theology and even Catholic social teaching does not align neatly with any political party.”

I’m certainly with him thus far.

Rightly noting that the Church, and the bishops, cannot and should not allow themselves to be seen taking sides in the partisan fray, Stowe said “it was very hard to speak out clearly about the former President of the United States,” though he himself found it necessary to do so. He also recapitulated his rather unvarnished criticisms of Donald Trump, and the many ways in which his policies and actions were “antithetical to what the Church teaches about the dignity of the human person and the sanctity of human life,” criticisms which I certainly share.

What I found perplexing was the bishop’s reticence to apply the same prophetic clarity on the importance of human dignity, and the need to defend it against politicians who act against it, when looking across the aisle.

Asked about Joe Biden’s unqualified support for legal abortion, Stowe’s logic becomes somewhat harder to follow.

“There is no disagreement among the bishops about the immorality of abortion or the desire that the extinction of life in the womb not be protected as a constitutional right,” he said. “But it is a complex issue for a responsible Catholic officeholder who recognizes the law of the land and must survive within the dynamics of a political party, believing what the Church teaches, but unclear as to how that should relate to the law.”

As a point of clarity, Biden does not believe what the Church teaches on abortion, or the reality of human life beginning at conception, and he has said so explicitly. But, this to one side, Bishop Stowe’s argument that opposing the taking of innocent human life becomes an understandably “complex issue” for someone looking to climb the greasy pole of party politics will strike many as baffling, as will his view that bishops should “listen to [politicians] before presuming their reasons for supporting policies that are objectively immoral.”

There would not seem, to me anyway, to be any acceptable reason for supporting “objectively immoral” policies — certainly not the pursuit of the power of high office, and the presumption Stowe warns against is simply that no such reason is or could ever be acceptable.

The bishop’s apparent argument would seem to vindicate and excuse the most damning accusation made against Biden’s campaign for his party’s nomination: that he sloughed off his adherence to Church teaching, and with it any responsibility to defend the lives of the innocent unborn, as a mere matter of political expediency on his way to the White House. That doesn’t seem all that “complex” to me, but it does seem like a big problem.

Given his own understanding of Church teaching as sitting outside, and at odds with, both parties, I would have hoped that a bishop as forthright in his views as Stowe would be able to look across the political divide and say out loud what many of us have long believed: that partisan affiliation in our current politics is irreconcilable with the fullness of the Church’s teaching, and has been toxic to the faith of so many Catholics who adopt it — our current president a case in point.

A truly anti-partisan voice from the bishops could accomplish much in keeping the Church above the party-political fray while calling Catholics to shape their political engagement according to the only identity that matters — that which flows from their baptism.

It could also do much to unite the bishops, who themselves, as Stowe’s interview appears to illustrate, often appear as willing as anyone else to pick a side and defend their own lesser of two evils. Sadly, that voice has yet to emerge.

As long as bishops appear willing to grant a special exception to politicians, of either party, and excuse the inexcusable as a necessary means to power, there is little reason to expect the conference to attempt more than papering over the partisan divide running through so many of our parishes.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity